In 1988, Eclipse comics was celebrating its ten-year anniversary as a publisher. Founded by Jan and Dean Mullaney, Eclipse was one of the earliest entrants into the nascent Direct Sales marketplace of Comic Book specialty shops. The company was also a proponent of creator-ownership and offered a better publishing arrangement than the mainstream outfits of the era. Over that decade, Eclipse had put out a lot of good work, though of late their efforts had been shifting away from what had once been their bread and butter.

At the beginning, Jan and Dean as well as their editor Cat Yronwode, had been fans of the comic book scene in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Consequently, a lot of their initial output was built around those creators who were particular fan favorites in that era, in particular writers such as Don McGregor, Steve Gerber and Steve Englehart. They were also invested in the growing movement to create more sophisticated stories for more adult audiences, works of personal expression that operated in a number of different genres beyond the tried and true super hero format.

But the thing Eclipse found as the decade of the 1980s wore on was that, while their intentions were good, the Direct Market was just as much enamored of super heroes as the mainstream newsstand outlets. Consequently, they began shifting their publishing focus over time, releasing more and more series that had a super hero bent to them, for all that most of them also were works by interesting key creators and were a bit off the beaten path of what a Marvel or DC might release.

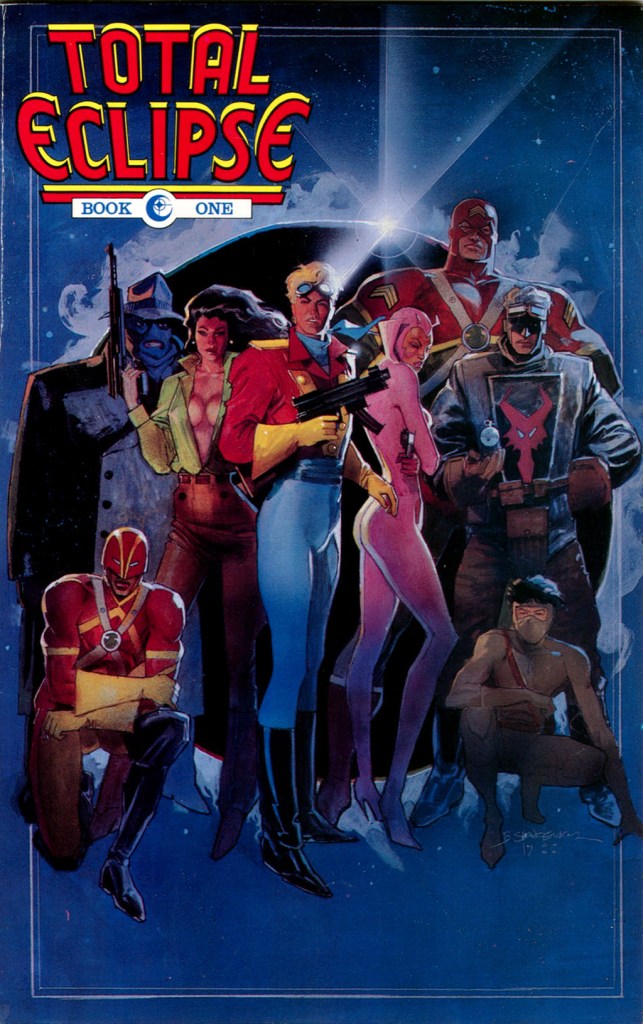

Which brings us back around to Eclipse’s 10th anniversary. To celebrate this milestone, the firm decided to release a special series–one built in emulation of the popular new movement in comic books at that time. TOTAL ECLIPSE would be a line-wide crossover series bringing together characters from throughout the Eclipse publishing line, including heroes both company-owned (Eclipse had begun a number of titles to develop a nascent super hero universe by this point) as well as creator-owned. So it was to be unflinchingly commercial, if at odds with some of teh foundational ethos that teh outfit had been founded upon. But needs must.

In an attempt to made TOTAL ECLIPSE as appealing to fans and retailers as possible, in particular ones that hadn’t given the company the time of day to any great extent, the company enlisted the services of writer Marv Wolfman to write the crossover. At the time, Marv was best-known both for the top-selling NEW TEEN TITANS as well as for having written CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS for DC, largely considered to be the best of the big crossover series.

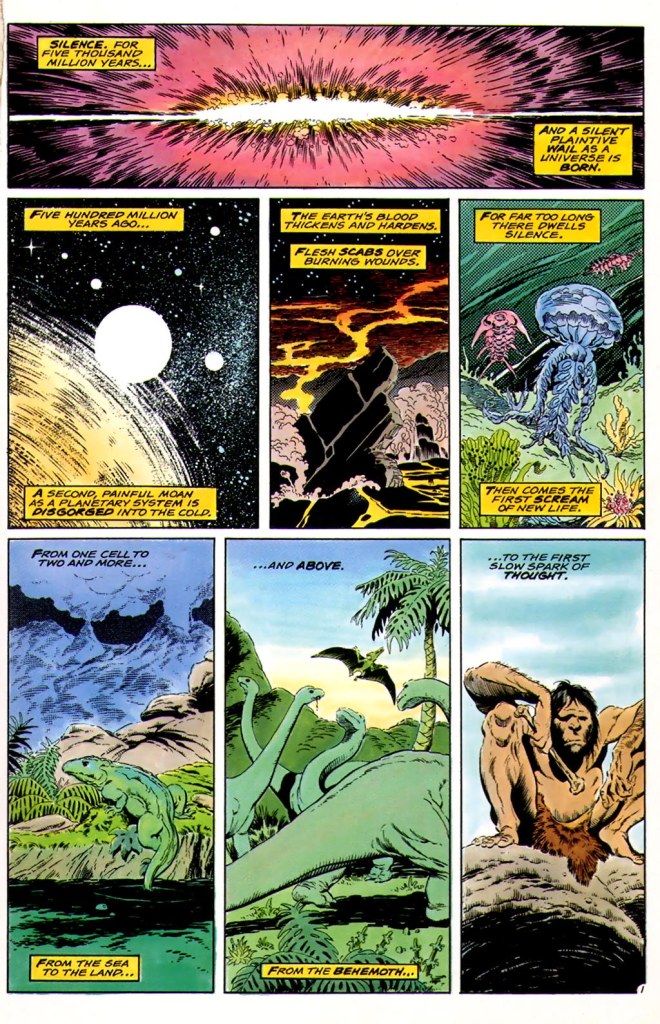

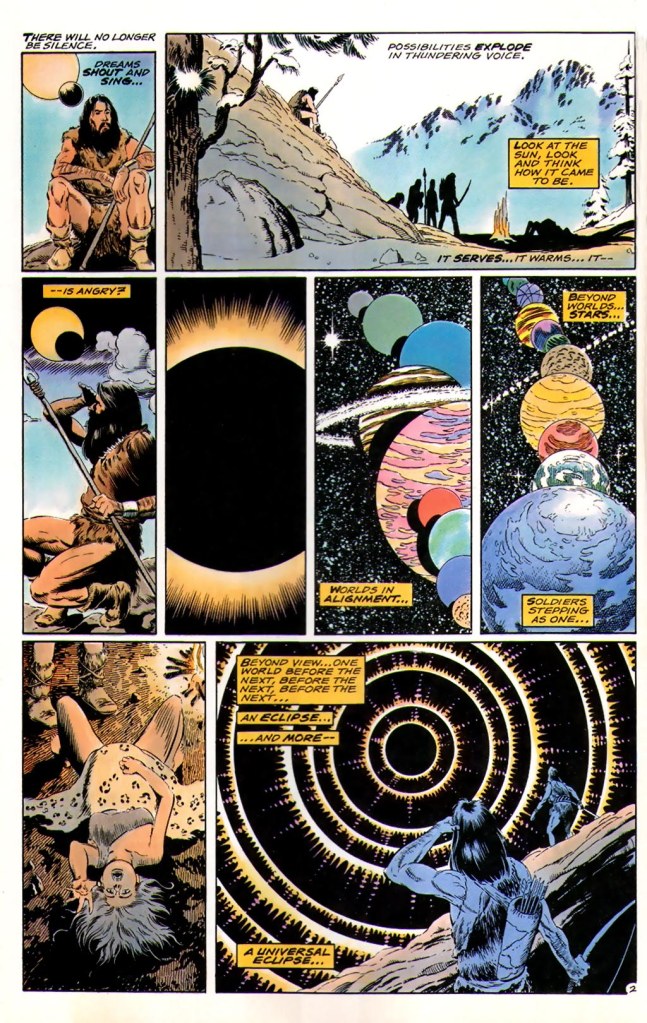

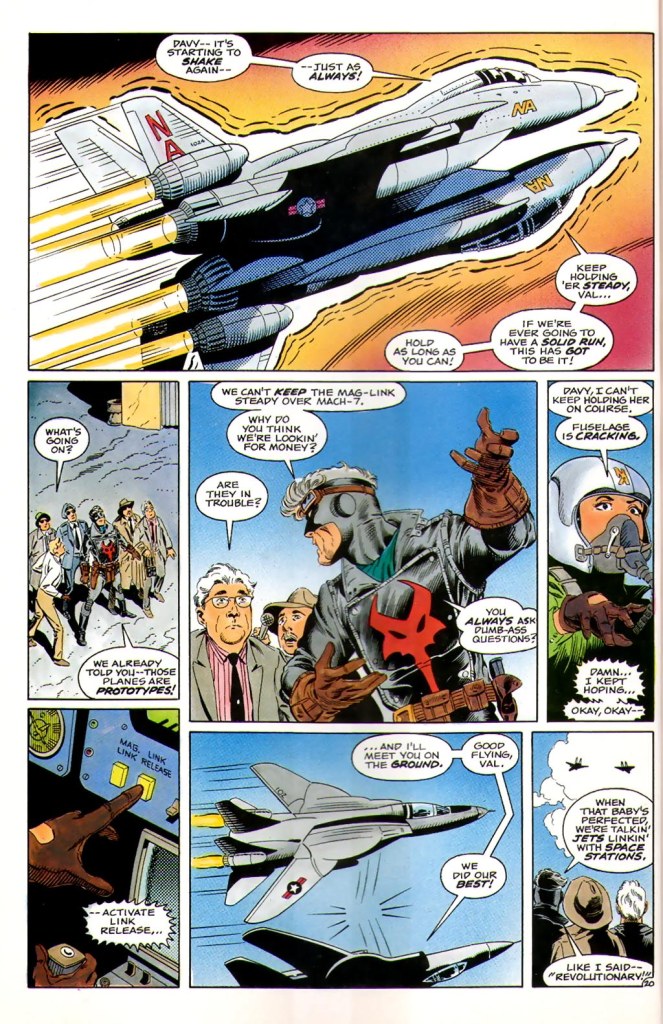

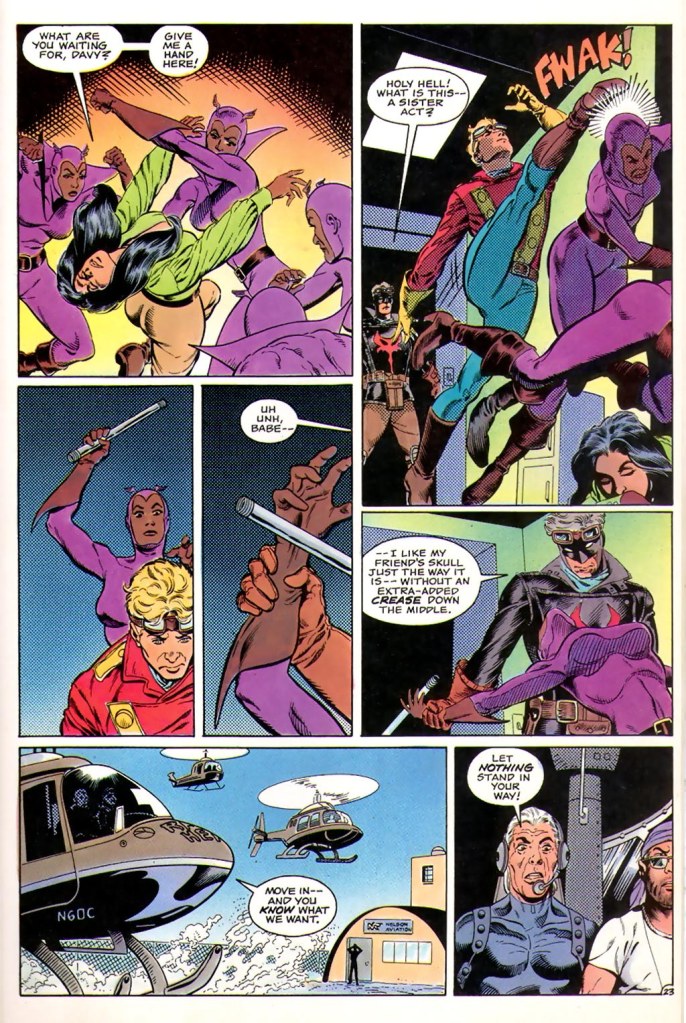

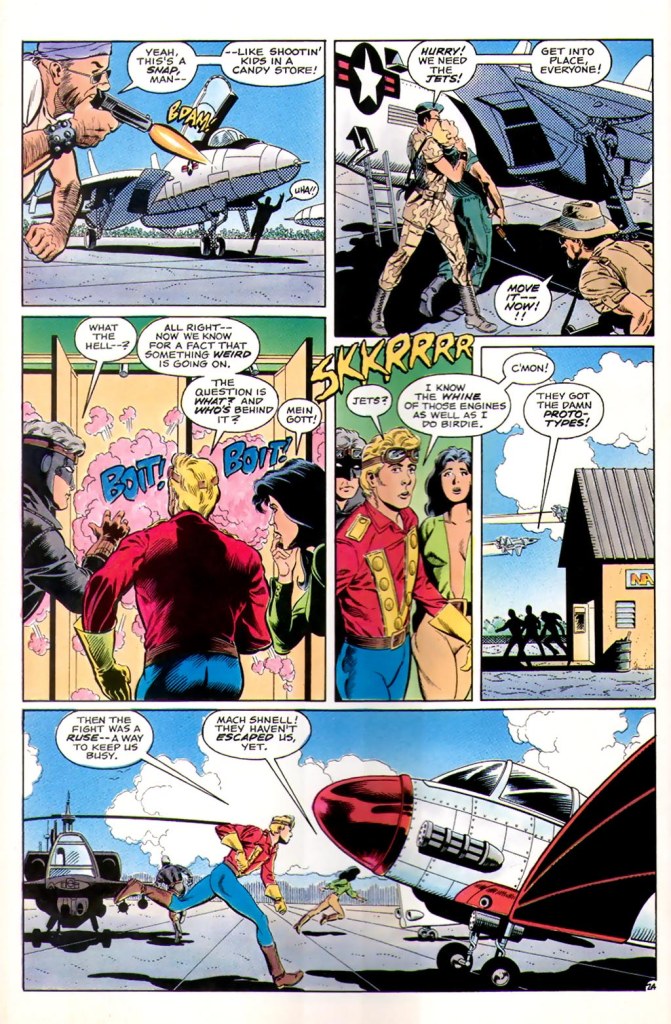

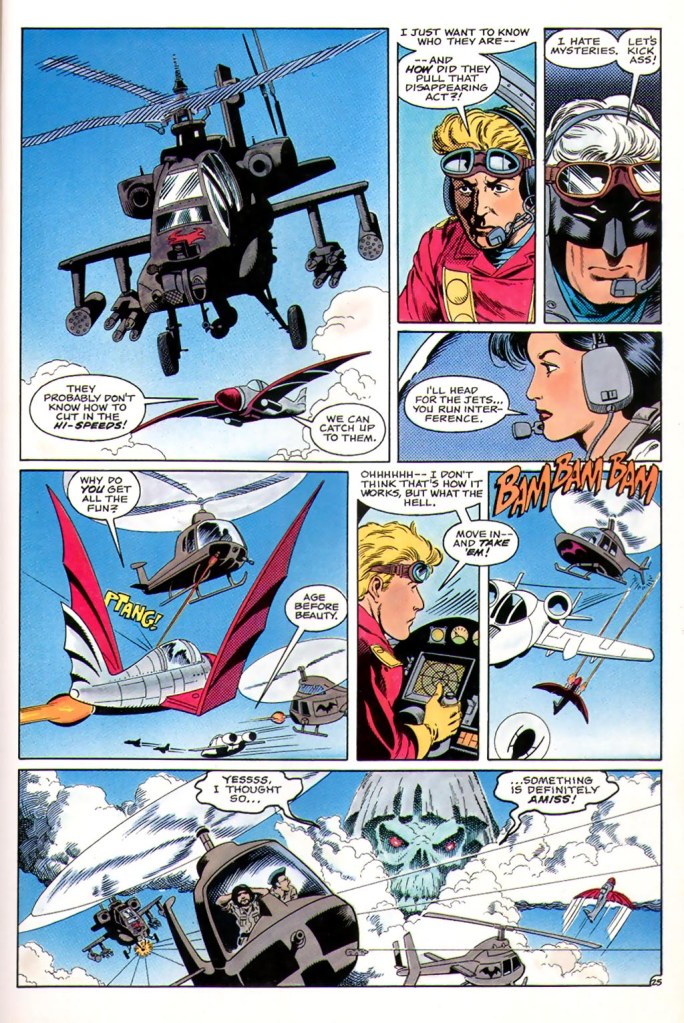

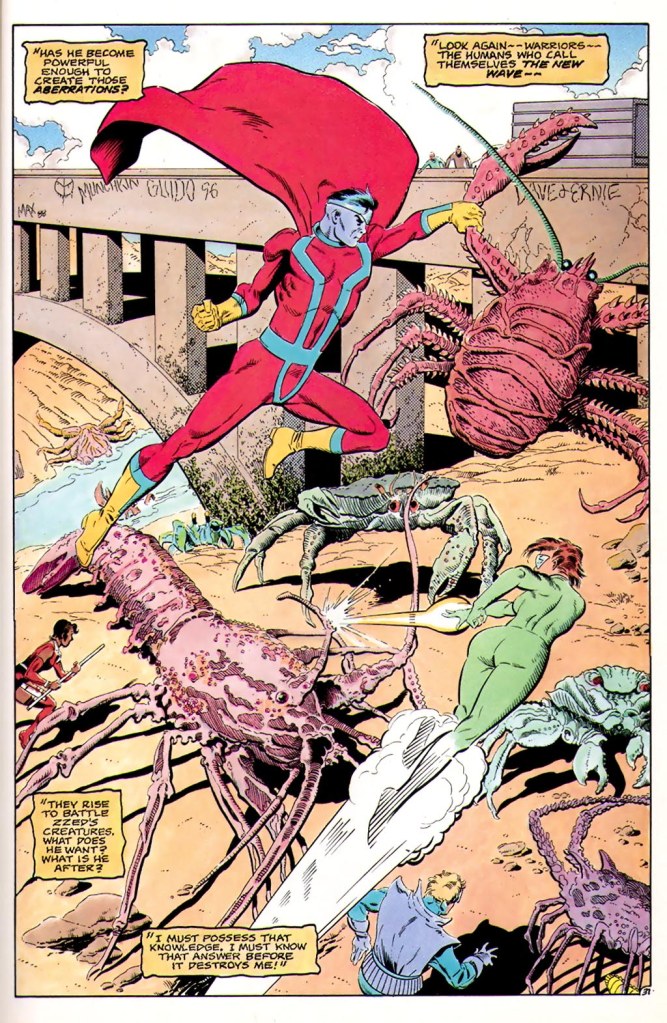

To illustrate the project, which was going to involve a host of characters drawn in a host of styles in their own series, Eclipse lined up Bo Hampton, one of a pair of brothers who had been doing fantasy and high adventure series for the most part. Hampton wasn’t as exciting or detail-oriented as CRISIS’s George Perez, but he had a straightforward commercial style that was more likely to appeal to the mainstream super hero readers that Eclipse was chasing than many of their other artistic options. Popular artist Bill Sienkiewicz was commissioned to paint the covers to the series.

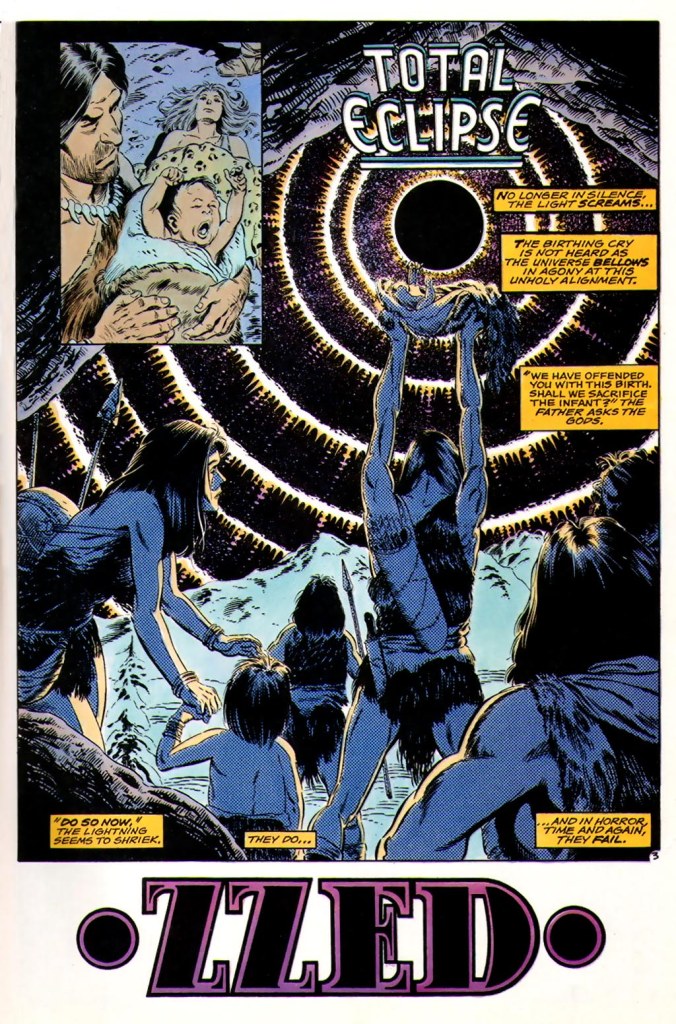

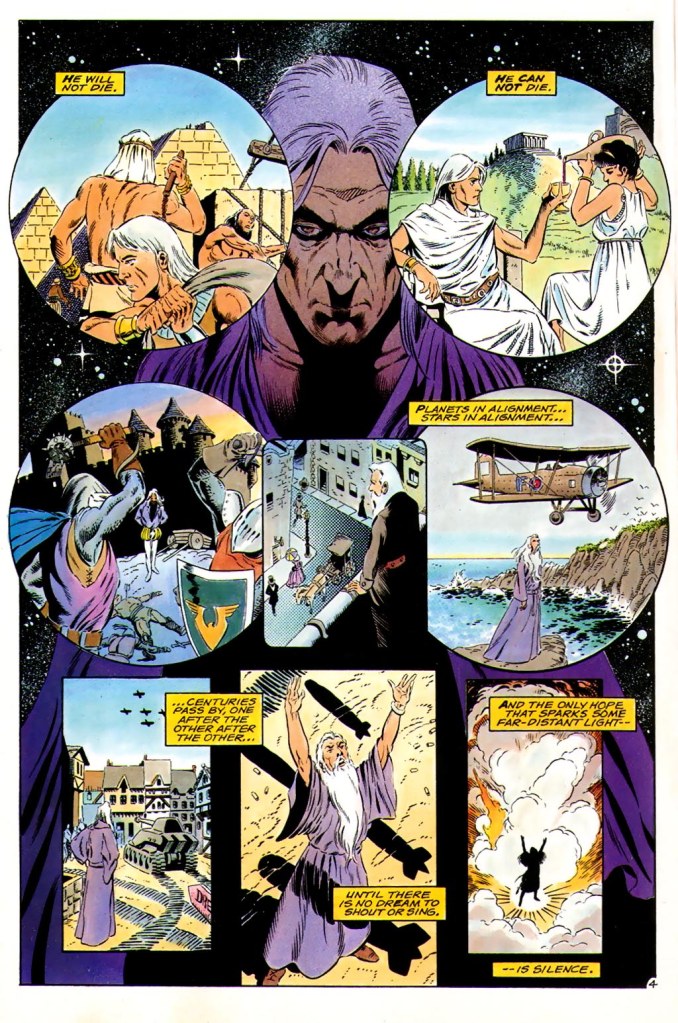

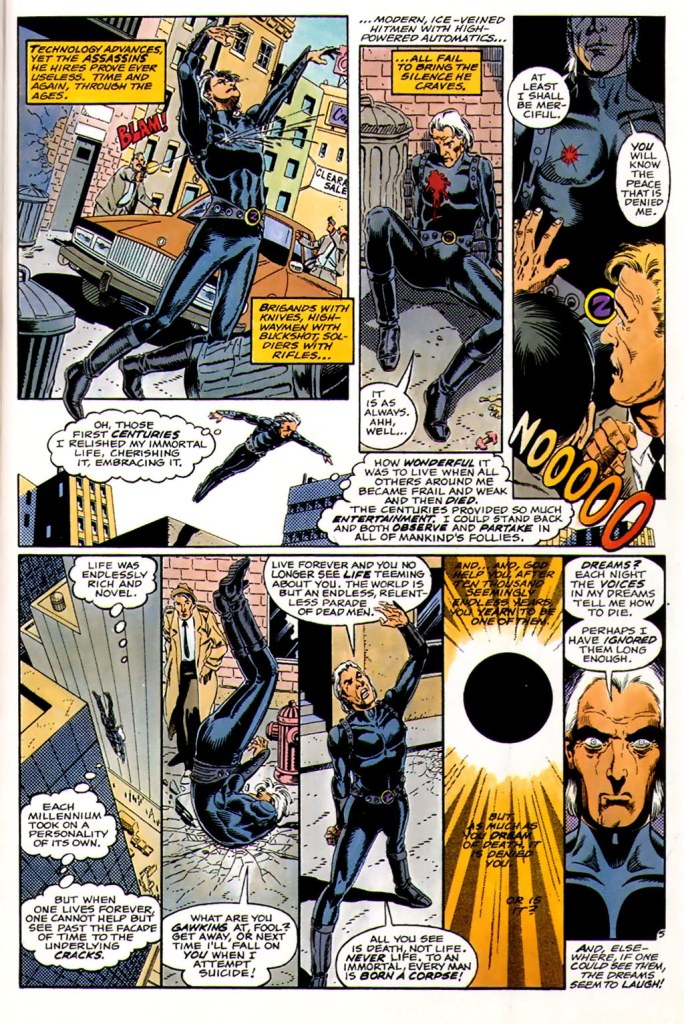

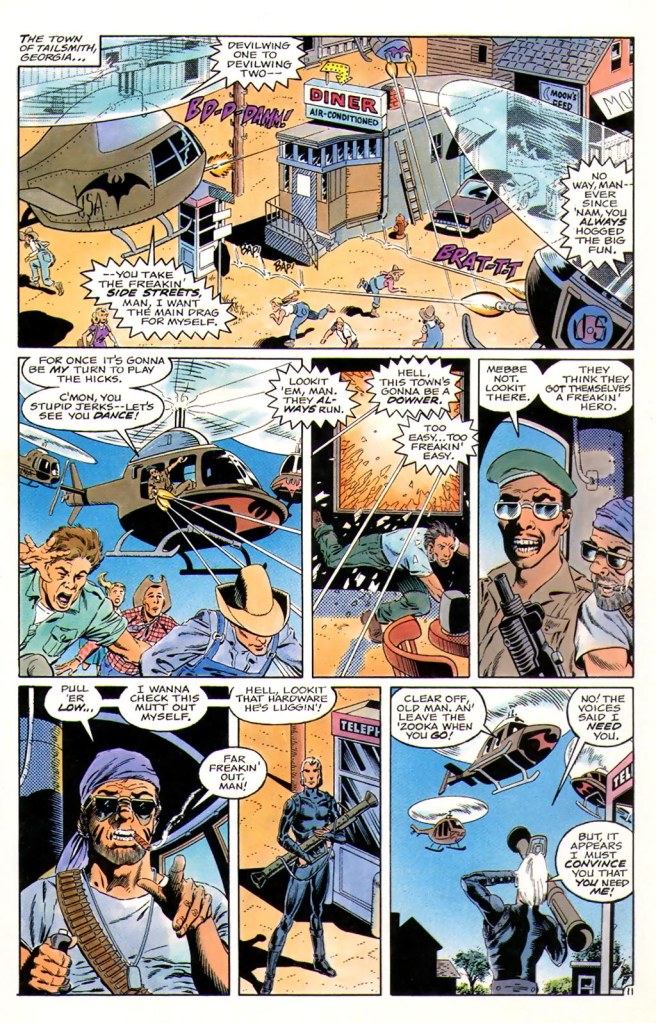

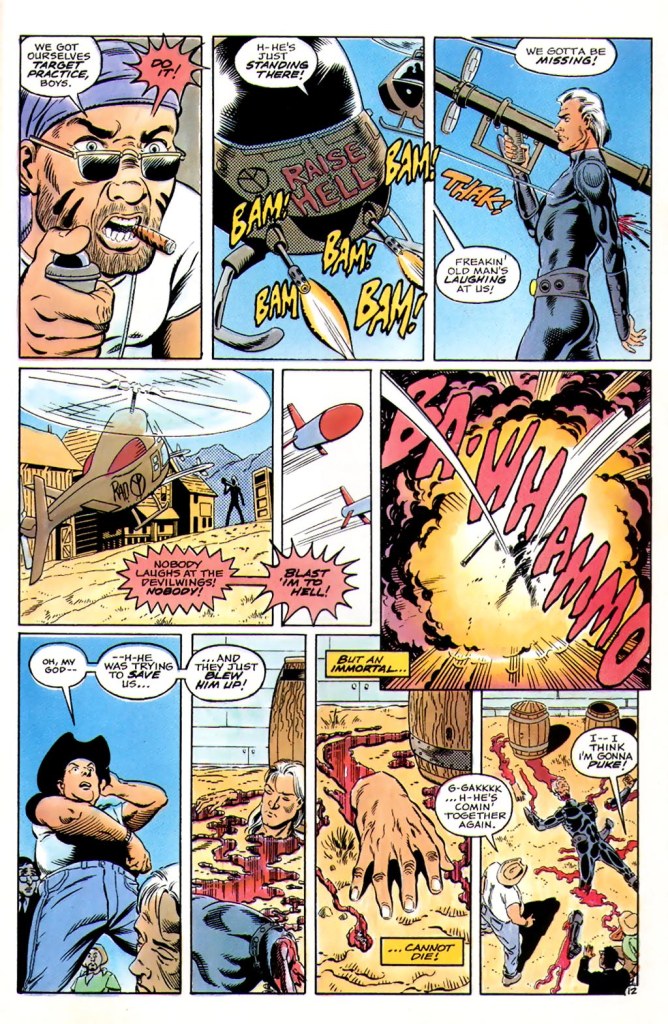

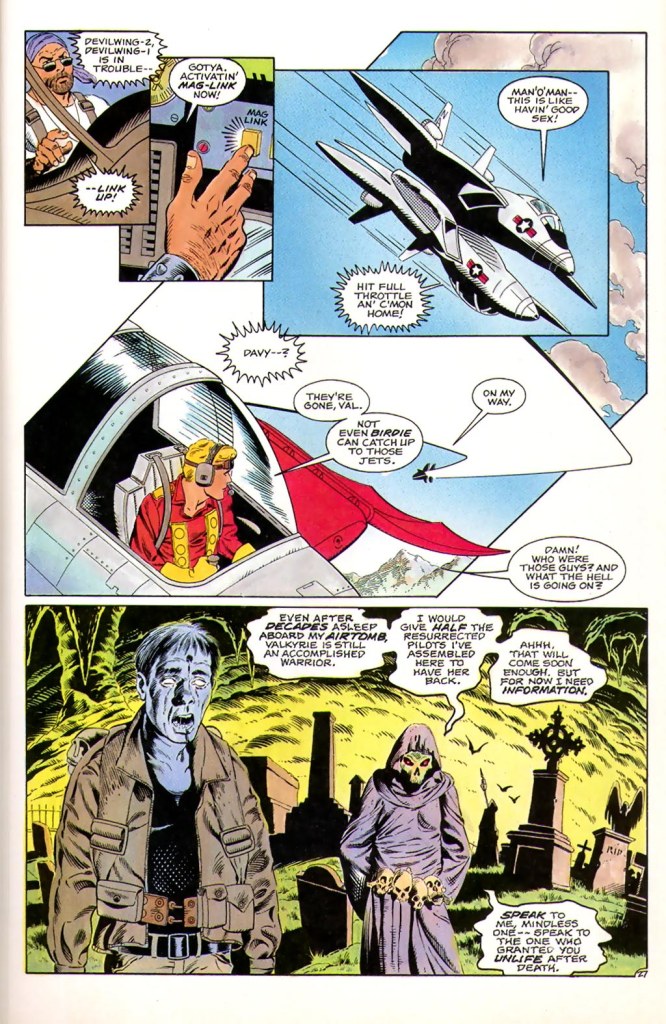

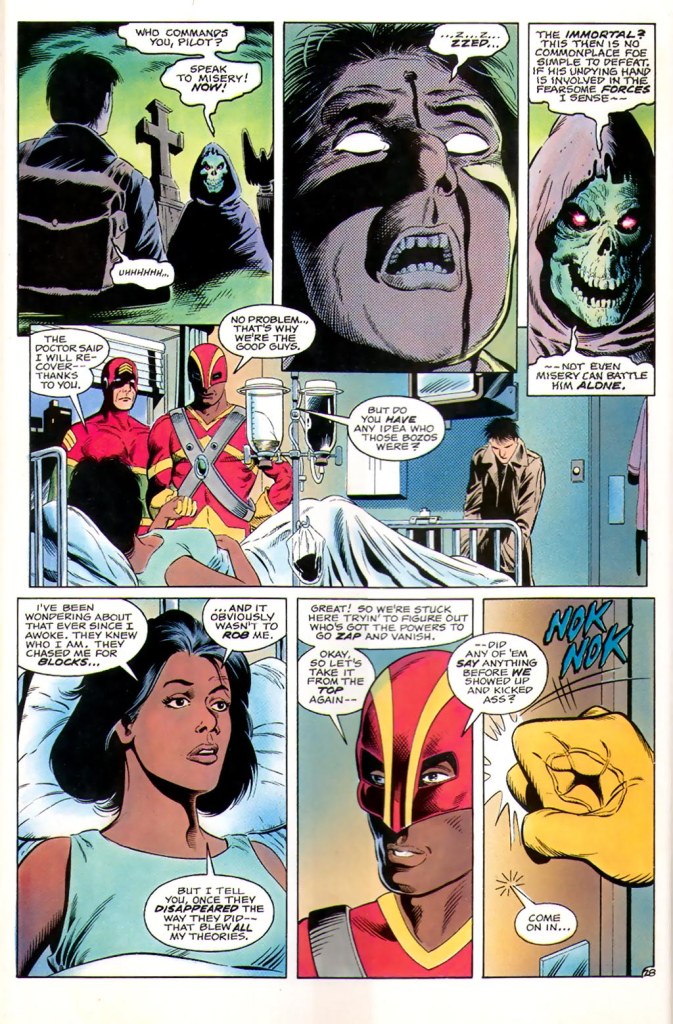

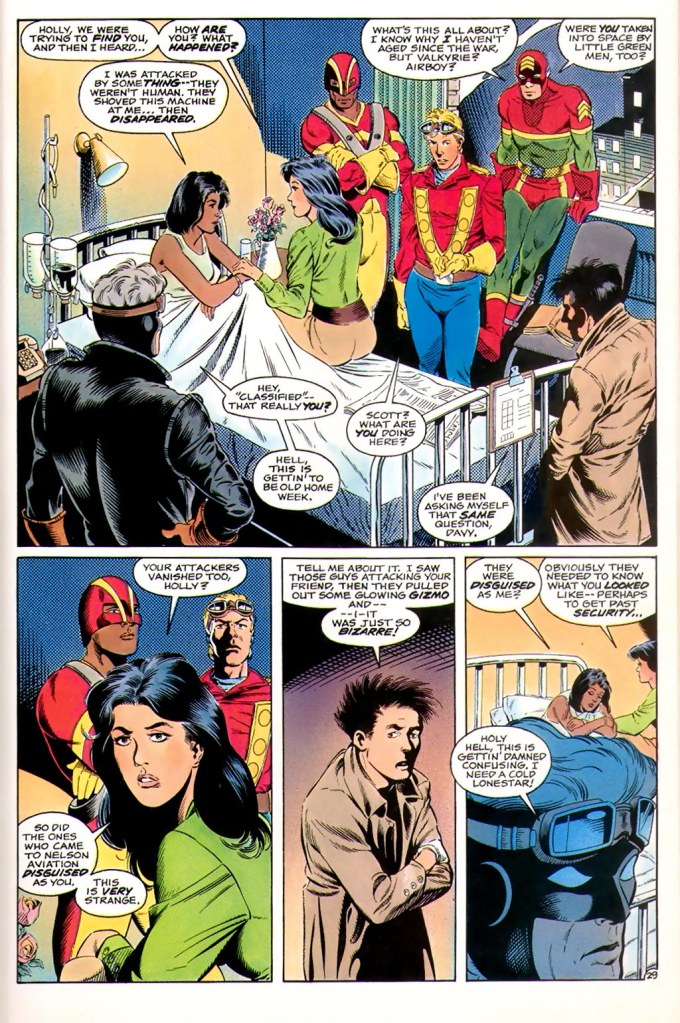

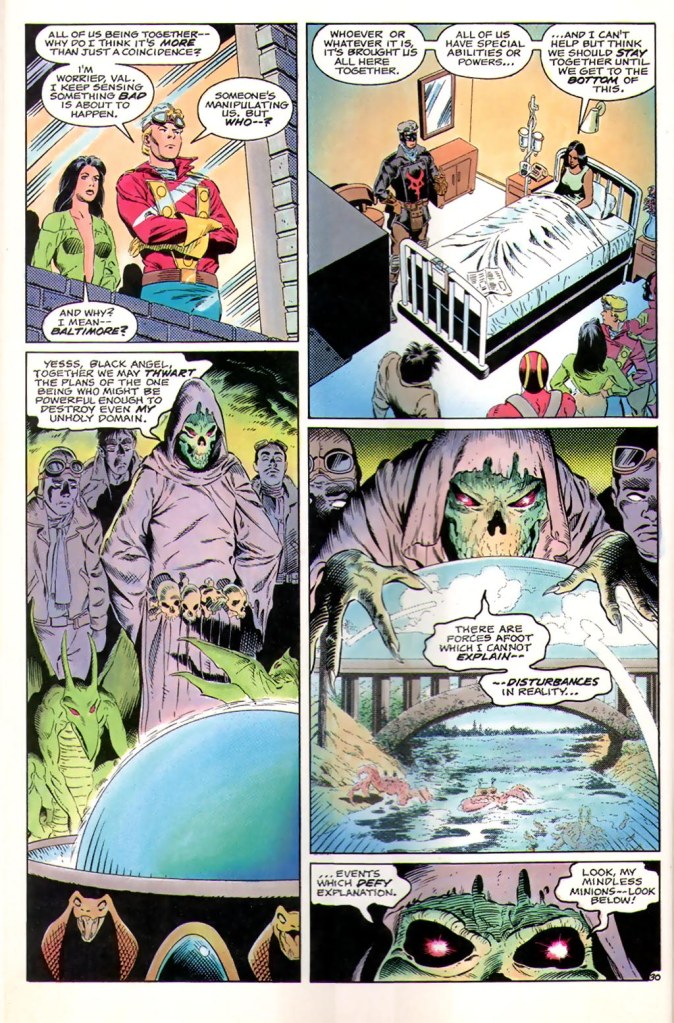

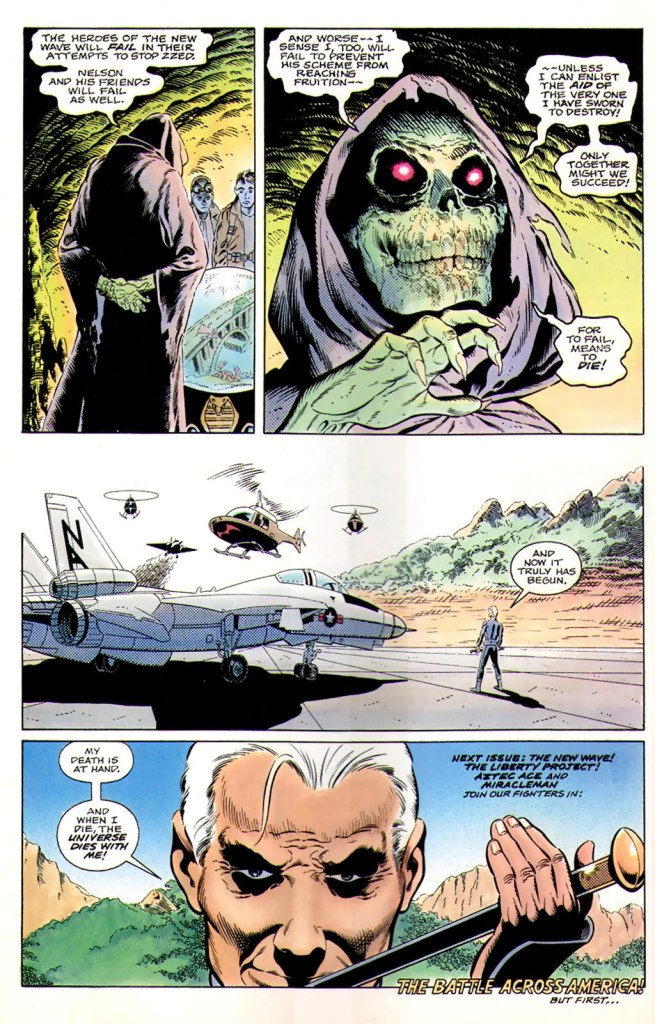

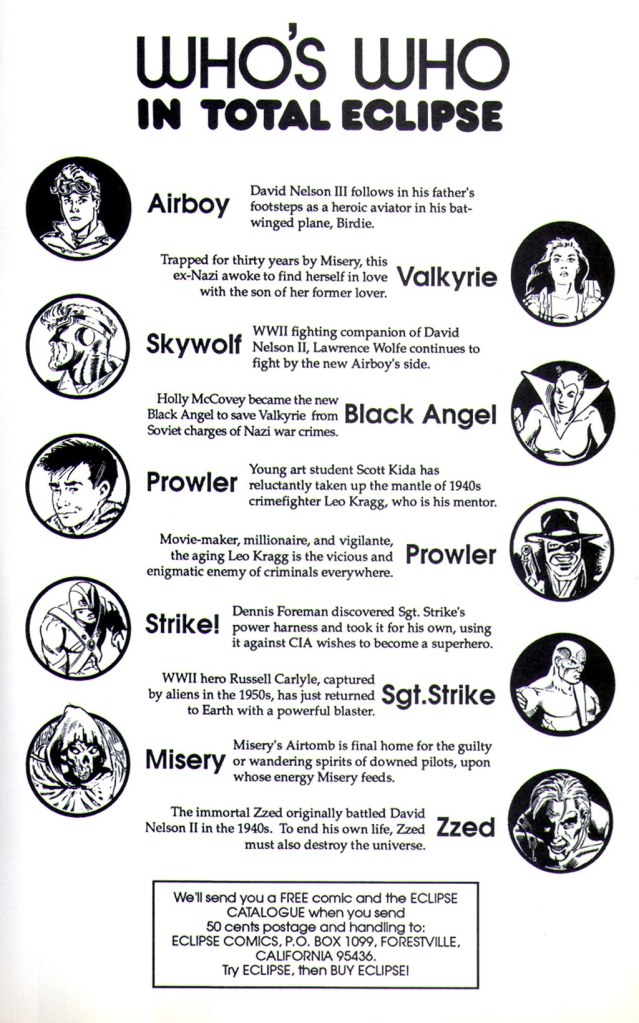

In coming up with a plot central enough and massive enough to unite an assortment of Eclipse characters from across time and space, Wolfman hit upon Zzed, an immortal villain from a pair of Airboy stories first published in the Golden Age. Eclipse had revived AIRBOY in a new series with the original hero’s son having taken up the name, so this fit in well with the prototypic universe that Eclipse was constructing. It did mean that pretty much nobody among the audience would have read the original Zzed stories at the time that TOTAL ECLIPSE came out, but using such obscure and ancient continuity had never stopped Roy Thomas before.

As an additional push, Eclipse decided to release TOTAL ECLIPSE in what was then largely known colloquially as the “DARK KNIGHT format”–that is to say squarebound with cardstock covers and a higher overall price point. Since the release of Frank Miller’s DARK KNIGHT RETURNS two years earlier, this format was seen as a signifier of a project that was more adult-oriented than the typical super hero comic book, and had been used only sparingly since then. But the floodgates were about to open on it, and TOTAL ECLIPSE was far from the only release in 1988 and 1989 to be put out in that format, thus blunting its effectiveness.

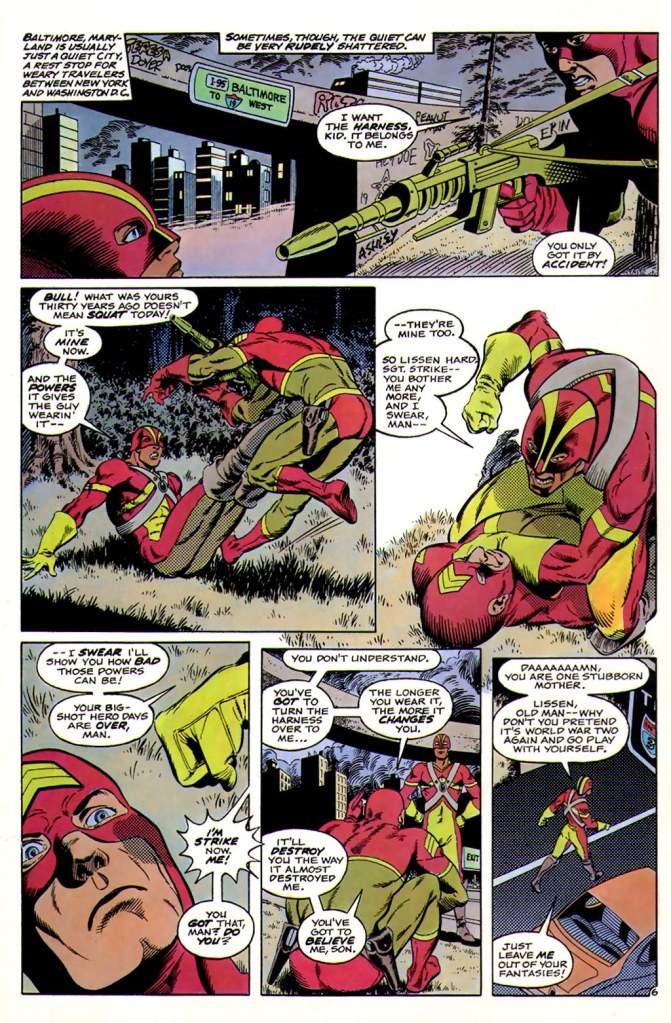

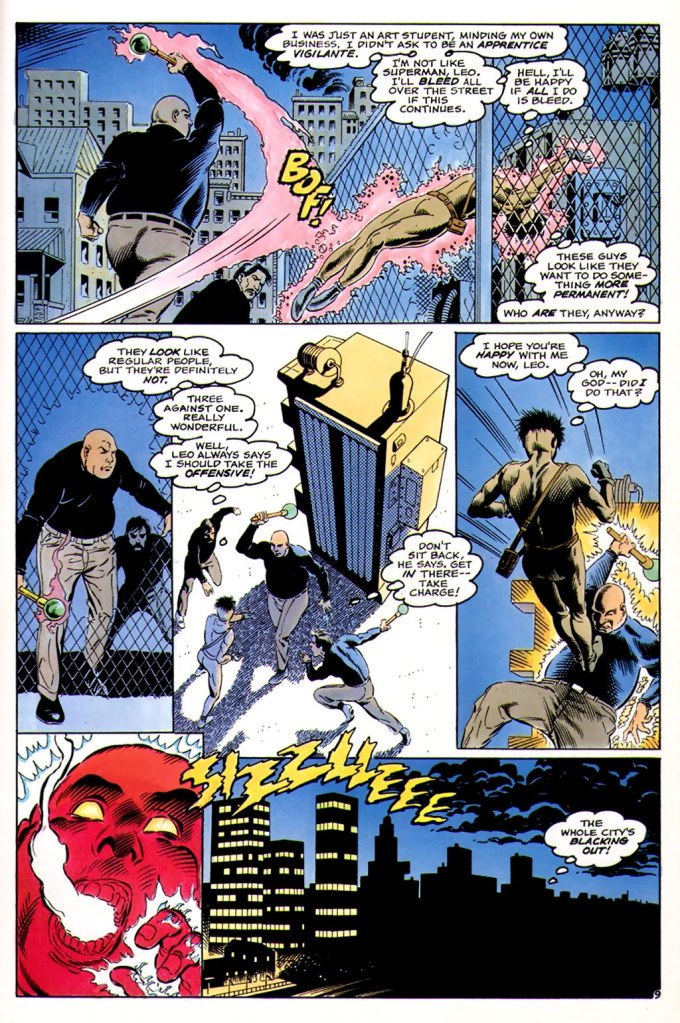

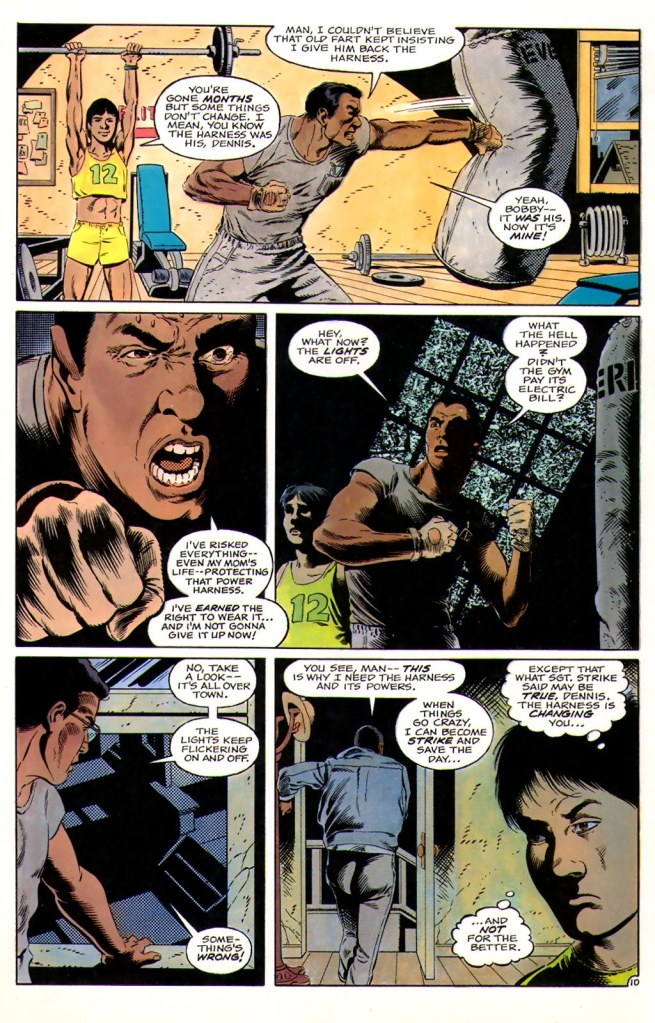

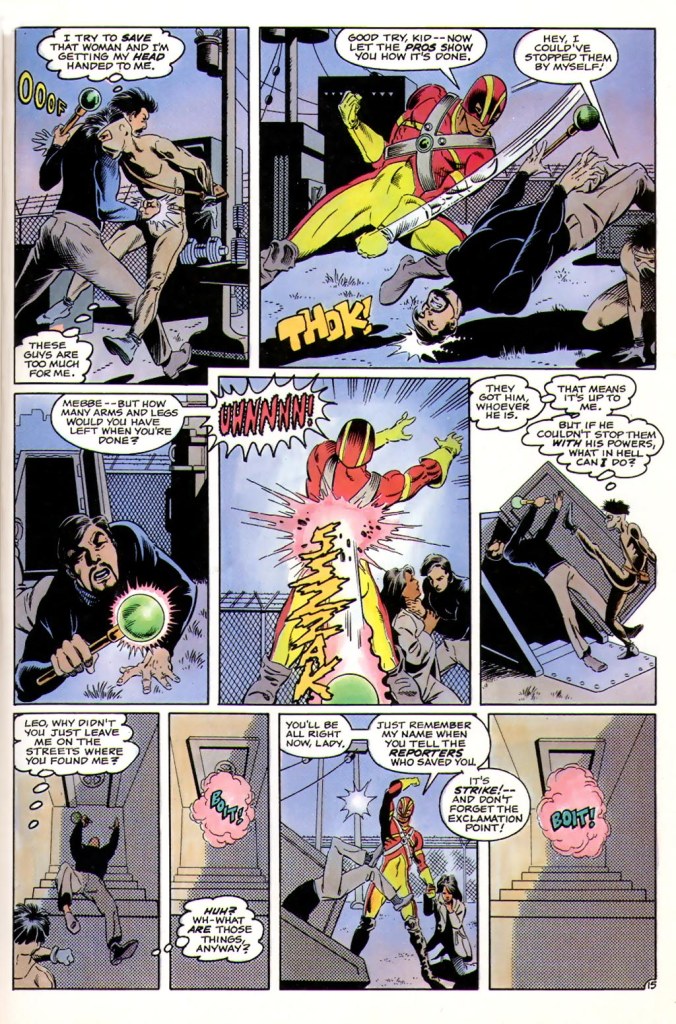

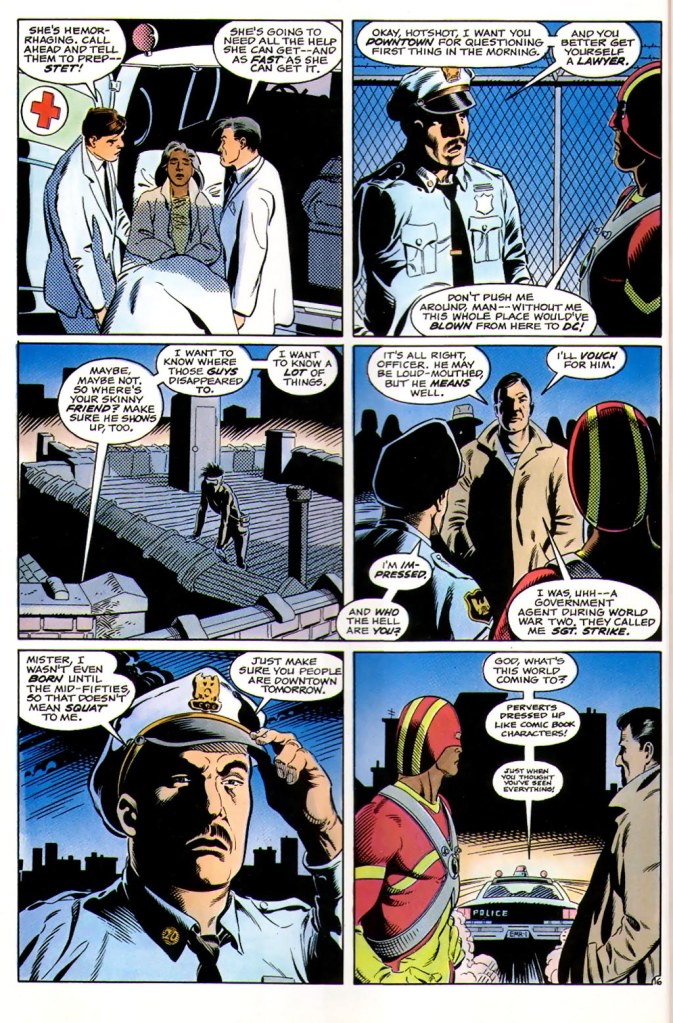

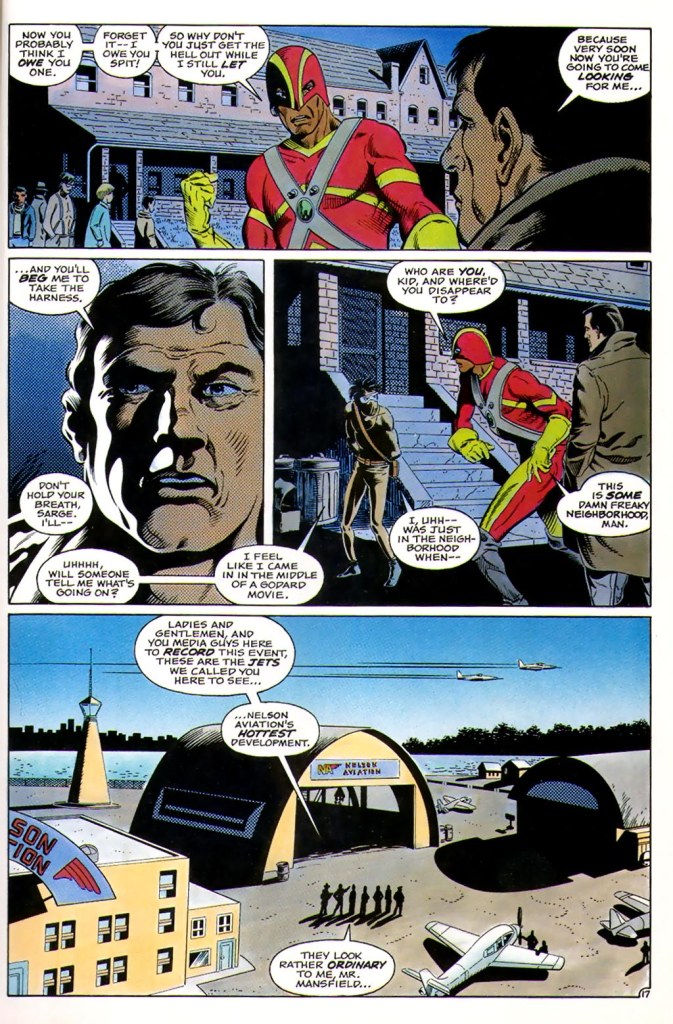

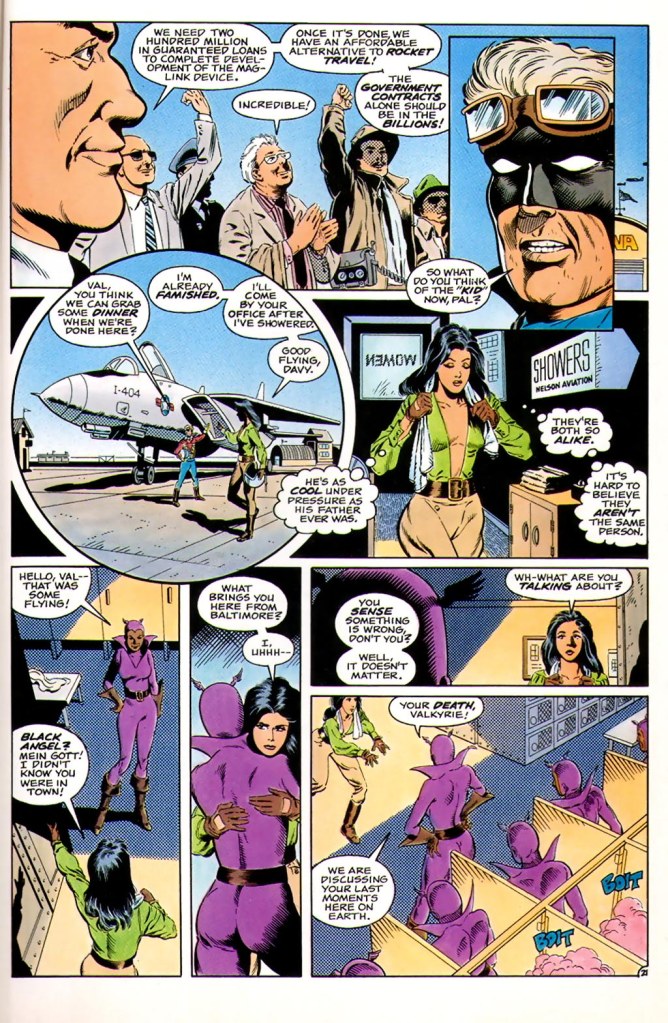

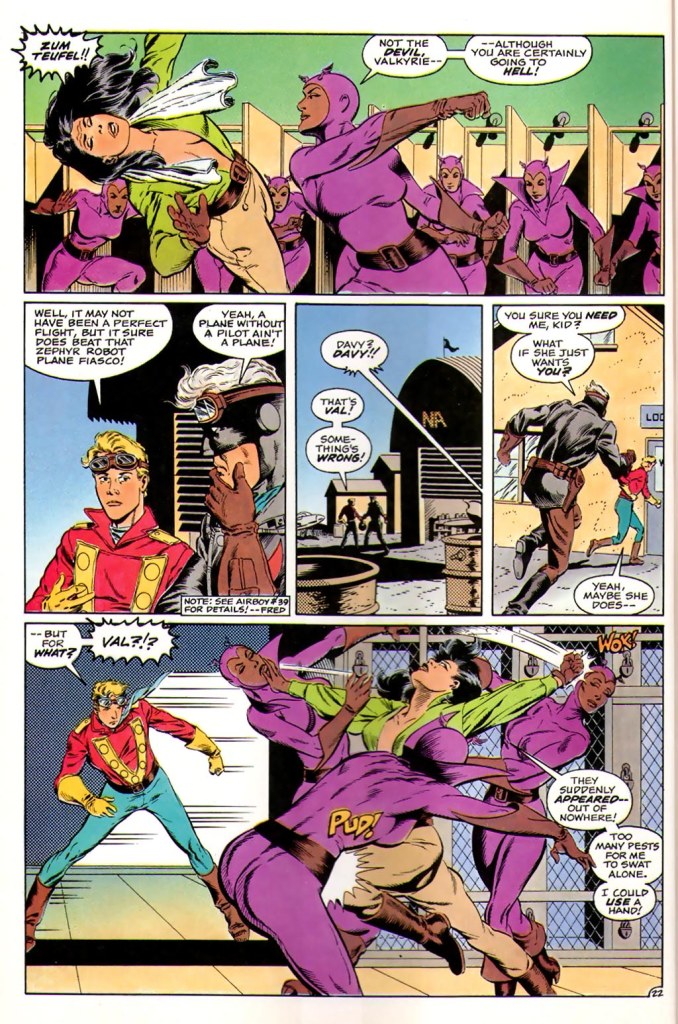

The first chapter of TOTAL ECLIPSE largely confined itself to characters who were a part of Eclipse’s home-grown super hero universe: Airboy and his fellow aviators Valkyrie, Sky Wolf and Black Angel, the super hero Strike and his WWII-progenitor Sgt. Strike, the Prowler and his new protege, and the members of the New Wave, a super hero team that headlined their own series for a short while. Eventually, though, the story would branch out to include a variety of other characters from other realities, including Aztec Ace, the Black Terror, the Liberty Project, Miracleman and even Beanish from Tales of the Beanworld.

Probably the best-remembered issue of the run of TOTAL ECLIPSE is #4, which included a Miracleman back-up story by Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham, the first they would produce as a team. Eventually, that story would be reprinted as a part of their run on MIRACLEMAN after Alan Moore and John Totleben’s tenure came to a close.

As far as I can tell, TOTAL ECLIPSE sold all right but didn’t really set the comic book world on fire. Eclipse continued their publishing operations for another five or six years before throwing in the towel as the marketplace became more competitive. But the notion that TOTAL ECLIPSE would turn around the fortunes of the company’s haphazard super hero line died on the vine. It wasn’t a CRISIS or even a SECRET WARS II. But it was the first line-wide crossover attempted by an independent publisher.

I got one issue when it was new. Got the whole thing on eBay more recently. Not great art but I found it great fun.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As far as I recall, the Direct Market may have been “just as much enamored of super heroes as the mainstream newsstand outlets” — and maybe moreso, since it was built of superhero fans, while the newsstand market still supported Archie and Sgt. Rock and other such books — but it was enamored of Marvel and DC superheroes, not anyone else’s, back then.

MIRACLEMAN did all right, on the star power of Alan Moore, and AIRBOY worked as more of an adventure series, but the books like STRIKE and NEW WAVE and LIBERTY PROJECT never made any real money. Eclipse was trying out that market, and hoping that TOTAL ECLIPSE could draw readers to the lesser-selling books, but it didn’t work. This is why ZOT! went black-and-white; it couldn’t afford color any more.

Eclipse’s meat was stuff that was adjacent to the mainstream, but not directly competing with what was in it — AIRBOY and MIRACLEMAN and SCOUT and such. But if it was straight superheroes and it wasn’t from Marvel and DC, it was a serious uphill battle to sell it.

It wasn’t until Valiant and Image that that particular resistance was broken, and they broke it real good.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Most of Eclipse’s output wasn’t for me. I realized a few years ago I was after heroic fiction in most of my comic reading and Eclipse didn’t deliver the kind I liked even when they tried that route.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Loved their revised Airboy, seemed to follow the tone of the golden age one, though Valkyrie falling for the son of a man she loved was always a bit hard to chew over.

You should do Femforce and AC Comics. They managed to survive when all others fell to the wayside. Heck, I can’t even get my own comic book shop to carry their titles. They didn’t want to add more distributors, they tell me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have issues 2 & 4 of Total Eclipse and issues 1 to 17 and 23 of Miracle Man that I picked up in 3 different comics shops in 3 different cities. Can’t remember what my impression of Total Eclipse was but I know in Miracle Man’s case I have a problem with super-hero Earths with limited super beings.

LikeLike

This isn’t my fave stuff of artist Bo Hampton’s, but there are several good panels throughout. In general I like his work, and also his brother Scott Hampton’s, especially the painted stuff. I liked the covers to “Luger” a lot.

I read a lot of Eclipse’s output back then. Some work by Bruce Jones. I remember 4 Winds Studio’s big expansion, with titles like “The Prowler”, and “Strike”. Eclipse is where I first read stories written by Chuck Dixon. And I was into Kurt and James Fry’s “Liberty Project”.

Most of the line initially had a “rugged elegance” art feel that I liked, in the tradition of Williamson & Kubert. I guess ultimately leading back to Foster and Raymond. Jones, the Hampton’s, Tom Yeates, Tim Truman, Stan Woch. Lee Weeks, Jorge Zaffino. There’s a few Kubert School alumni included in my list.

First Comics followed with their own crossovers, with some really great Steve Rude covers.

LikeLike

As a retailer at the time, I remember issues of this shipping horribly late, which affected sales.

LikeLike

I was a big fan of Eclipse and First Comics. In fact, at their respective heights I probably enjoyed their comics more than much of what the Big Two offered.

LikeLike

+1 on First Comics, especially in the early years.

LikeLike

In the days before the Turtles became a big media franchise, they also carved out a niche doing “superheroes like, yet unlike, Marvel and DC.”

LikeLike

The company was also a proponent of creator-ownership and offered a better publishing arrangement than the mainstream outfits of the era.

The claim of “a better publishing arrangement” is debatable. Jim Starlin and Steve Englehart took their creator-owned features that Eclipse published to Marvel at the first opportunity. Later on, the Mullaneys apparently decided to welch on royalty obligations. Alan Moore has said that he never saw a penny of back-end money from the sales of Miracleman. Toren Smith, who packaged the company’s manga line, ended up suing Eclipse for non-payment and got a six-figure judgment against them. Neil Gaiman publicly called the Mullaneys “crooks.”

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing, Tom! I always enjoy your history lessons. Eclipse has long been a publisher that interested me and it is nice to have a little more info. Keep up the great work!

LikeLike