As I talked about yesterday, this was the second of two magazine-sized issues of THE SPIRIT that I got for Christmas 1978, ordered out of the Superhero Merchandise catalog. And like yesterday’s issue, this one offered a batch of classic Will Eisner Spirit stories from the long-running Newspaper circular that had run in the Golden Age, along with an assortment of other features and bits. These included advertising for Kitchen Sink’s other underground publications, books whose covers and descriptions frankly baffled me as a young reader. CORPORATE CRIME COMICS? MR. NATURAL? COMIX BOOK? What were these strange things? Far from being intrigued, they gave me an unsettled feeling, one that persisted for years whenever I’d cross the path of underground comics out in the wild. Accordingly, while I’ve now read my share of the undergrounds, I never really connected with them strongly.

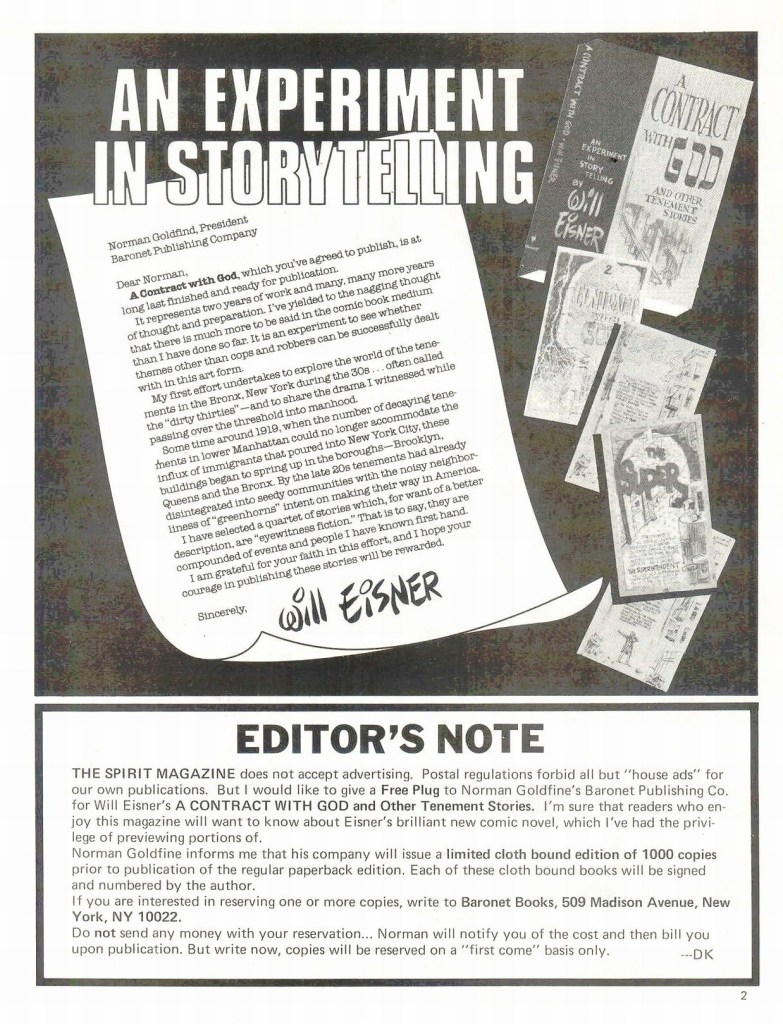

It was in this issue that I first became aware of Eisner’s first impending graphic novel, A CONTRACT WITH GOD. And again, I didn’t quite know what to make of it. But I got the sense that it was important somehow, and the brief glimpses that I’d get in subsequent issues drove my interest. But it was an actual book with an actual book’s price tag, and so it would be several years before I’d buy a copy of my own and read the thing. At this point in his life, Eisner wasn’t especially interested in the Spirit apart from a way to bring in some scratch for work done decades earlier. But he was very interested in the manner in which the undergrounds allowed for comics that were a form of self-expression, and he pursued a more literary approach to his current material.

As last time, the letters page included correspondence from two other practitioners of the art: Michael T. Gilbert, whose character The Wraith had been heavily modeled on the Spirit, albeit in anthropomorphic dog form. And Robin Snyder, editor and publisher who would eventually put out the long-running publication THE COMICS dedicated to obscure corners of comic book history, was also present. Of course, I wasn’t yet familiar with either man when I first read this issue.

One of the affectations that the Kitchen Sink SPIRIT Magazine carried over from the earlier Warren incarnation was adding greytones to the artwork. This was something of a necessity, as the Spirit sections had originally been created to include color, but color printing was cost-prohibitive for both Warren’s and Kitchen’s outfits. This work was typically done fairly well, with only an occasional page or story going awry.

Spirit stories of this era were seven pages long, and so the final page of the Spirit Section, which itself had dropped from 16 pages at its inception to a mere 8, was filled by a single-page gag strip called Clifford. Beginning with this issue, Kitchen began running a Clifford strip after each Spirit story. These strips, produced by a young Jules Feiffer during his period working for Eisner, were pretty entertaining. But they had a secondary purpose as well: There were only so many Spirit stories available, and so running a bunch of Clifford pages in every issue meant that one fewer Spirit story would be used up. Kitchen was thinking ahead.

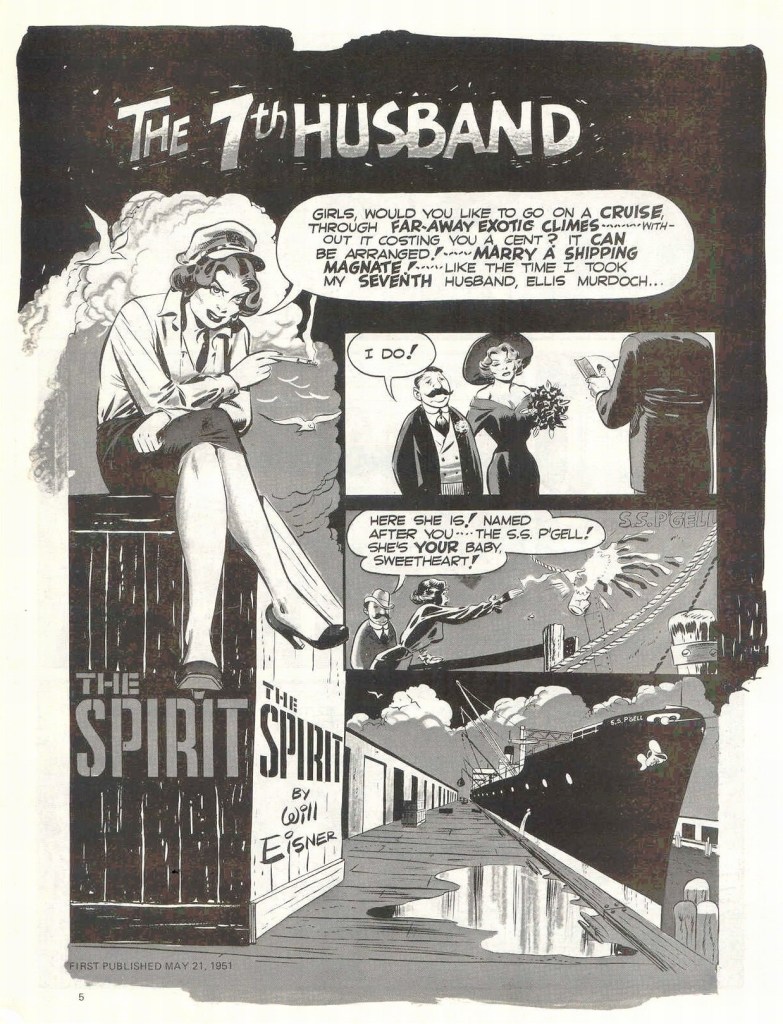

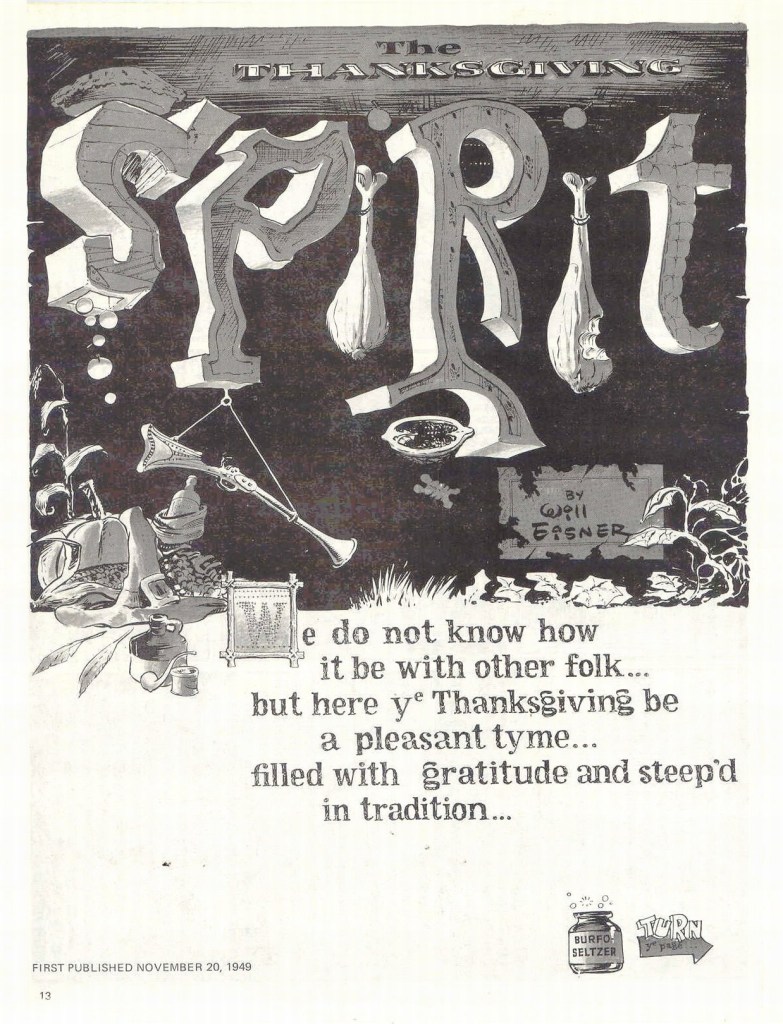

As usual, there’s not really much of any rhyme or reason to the selection of the stories in this issue. It’s just six adventures culled from throughout the postwar years. They included this outing, one of Eisner’s regular holiday-themed tales. Since the Spirit was appearing on a weekly basis in the newspaper, the approach of different holidays was more immediate and meaningful to the audience. So Eisner did stories such as this one on a regular basis. The need to generate 52 stories a year was a grueling mistress, so anything that gave Eisner and his studio a leg up on story was greedily utilized.

I do recall that Future Death was one of the stories that my sixth grade teacher Mrs. Seaman read to the class. It concerns the case of a Professor who claims that he created a functioning time portal and traveled to the far future year of 1970. It was fun seeing Eisner’s wild stab at the world twenty years hence from the vantage point of eight years later. Anyway, in that world, the Professor learns that all firearms have been outlawed, and as he brought his pistol with him for protection, he was then the most powerful man in the world. An aged Spirit tries to stop him, but the Professor accidentally shoots him at point-blank range. Aghast at his crime, the Professor flees back through his portal, carrying as proof of his journey one of the Spirit’s gloves. Both the Spirit and Commissioner Dolan write him off as a kook–but after the Professor leaps in front of a passing car, so guilt-ridden by his crime is he, they’re both disquieted to find that the glove he had brought with him fits the Spirit perfectly.

Eisner also contributed a new 3-page story to the magazine, another very grounded story completely unlike the noir adventures of the Spirit. I thought it was well done, but didn’t quite know what to make of it, so steeped in the culture of another time and place was it. More and more of Eisner’s new work would reflect this sensibility over time.

The final story in the issue saw print on the first day of January 1960 and involved Commissioner Dolan and the Spirit’s helpmate Sammy (a less offensive version of the earlier Ebony) answering mail from the readers. This was sort of like the precursor to the Marvel Handbook in a way, as it answered questions about the Spirit’s height and weight and his origins, some behind-the-scenes info from Eisner on the materials used to draw the strip, and the most important question of all: Why does the Spirit wear his gloves day and night…even when he goes to bed? This sure sounds to me like a question that had bounced around the Eisner Studio at some point, and was thereafter incorporated into the strip.

Love Eisner and the Spirit. One of my regrets is not being able to buy Spirit Archives when they were being released.

LikeLike

My local public library has them. The librarian who orders new books is a comics fan with a broad and interesting viw of the medium . . . .

LikeLiked by 2 people

I wish I could ask the artists back then ( 1940s-60s ) why they felt the need to do caricatures of people of colour. Was it company policy? Cause I find it hard to believe never seen or met any people of colour in their lives. Or why when they do Alien Races or Human Races of Colour ( ones they have in tribes ) or Hidden Races they leave out the women or only show a small number of them? Like during WW2 did the Japanese Ambassador to the U.S. have buck teeth and wear glasses, cause as a guy who grew up on Godzilla & Gammera movies and Johnny Sokko and His Flying Robot & Ultraman TV series I just don’t remember seeing any buck teeth Japanese actors.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In Batman/The Spirit#1 they left Ebony White out of that story even though they could have created a human version of him ( First Wave made Ebony White a woman ).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Darwyn Cooke did a better job of handling nno -white characters in his “Spirit” run.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Had Tom not done The Spirit I would never have remembered ( and just seen with my own eyes ) I have the Darwyn Cooke started Spirit series ( I could only remember The First Wave ).

LikeLike

Those caricatures like Ebony come from a stock type which has thankfully died out. The old Billy Batson valet “Steamboat” was another example. It traces back to the original Jim Crow/minstrel, e.g. here: jimcrowmuseum.ferris.edu/who/index.htm . Look at the picture on the middle-right of the page. That’s basically Ebony. Even great graphics geniuses like Eisner can’t always escape being of their time.

The “tribes” scene not having women comes from the fact that an adventurer meeting a nomadic people is generally going to be greeted by a group of military-aged men (or local equivalent), for dramatic reasons if nothing else.

In WWII, Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo really did have bad teeth and wear glasses 3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2011/05/theres-something-about-the-teeth-of-tyrants.html . He was quite (in)famous in popular culture back then, due to Pearl Harbor. Though today in the US, almost nobody besides WWII history buffs could identify him from one those Hitler-Mussolini-Tojo comic covers (i.e. if you took one of those covers, asked someone “who are these people”, many would be able to name Hitler, some Mussolini, but very few Tojo).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Seth F said:

“The “tribes” scene not having women comes from the fact that an adventurer meeting a nomadic people is generally going to be greeted by a group of military-aged men (or local equivalent), for dramatic reasons if nothing else.”

Also, in comics at least, it’s more trouble to draw a mixed batch of natives, as opposed to a bunch of males only distinguished if at all by height.

LikeLike

I’ve been reading old Phantom comic strips from the ’30s and was glad to see the artist portrayed the natives realistically instead of the then current stereotype.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Makes sense that they would be faithfully and respectfully represented in “The Phantom”. The character lives among them. He respect them. Eisner must not have given it much thought outside of the insensitive caricatures he saw around him.

LikeLike