In the latter part of the 1960s, change was beginning to be felt within the halls of venerable old DC Comics (then operating as National Periodical Publications.) The culture at large was going through a shift, and so the tried-and-true methodology that had kept the giant publisher on top was no longer working as well as it once had–new ideas and new approaches were needed. Unfortunately, for all that there was some realization in certain quarters that change was needed, in other areas, change was anathema. And so we come to the story of the aborted version of TEEN TITANS #20, a comic book that wanted to push the boundaries a little bit and speak to the time, and which almost got its creators drummed out of the business for the affront of daring to put forward–a black super hero.

When it started, TEEN TITANS was a bit of a silly comic book, a series that united the various sidekicks of popular characters as a group, its dialogue rife with dated pseudo-slang indicative of what middle aged white men thought that teenagers sounded like. But a shift began to happen when Dick Giordano was given oversight of the book upon his arrival at DC as an editor. This roughly coincided with a period when many of DC’s longtime writers were being quietly blackballed from the company for having the temerity of asking for some manner of pension plan for their many years of service. In their place, a new generation of young creators were brought in, people who were only too happy to be able to work on these books they loved so much (and unaware of what had befallen their predecessors.) Two of these newcomers were Len Wein and Marv Wolfman. In later years, each man would go on to create properties that would be enormous hits for the different companies at which they worked. But at this time, they were just a pair of progressives who were starting out, and who wanted to do stories more in line with the way the world was at that time. In their first TEEN TITANS story, which saw print in issue #18, they introduced Starfire, a Russian super hero who was depicted as being just as heroic and noble as any of his American counterparts (and who suffered suspicion from the Titans, in particular the conservative Kid Flash.) Flush from this success, the pair had another contemporary idea that they wanted to put forward: introducing an African-American super hero.

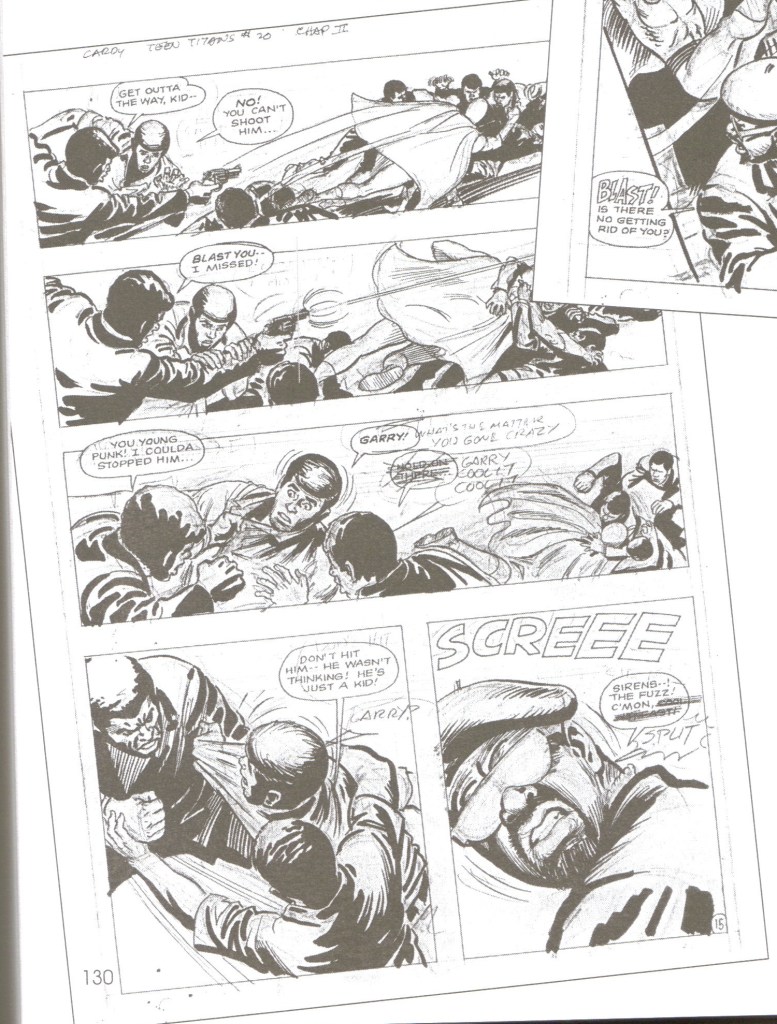

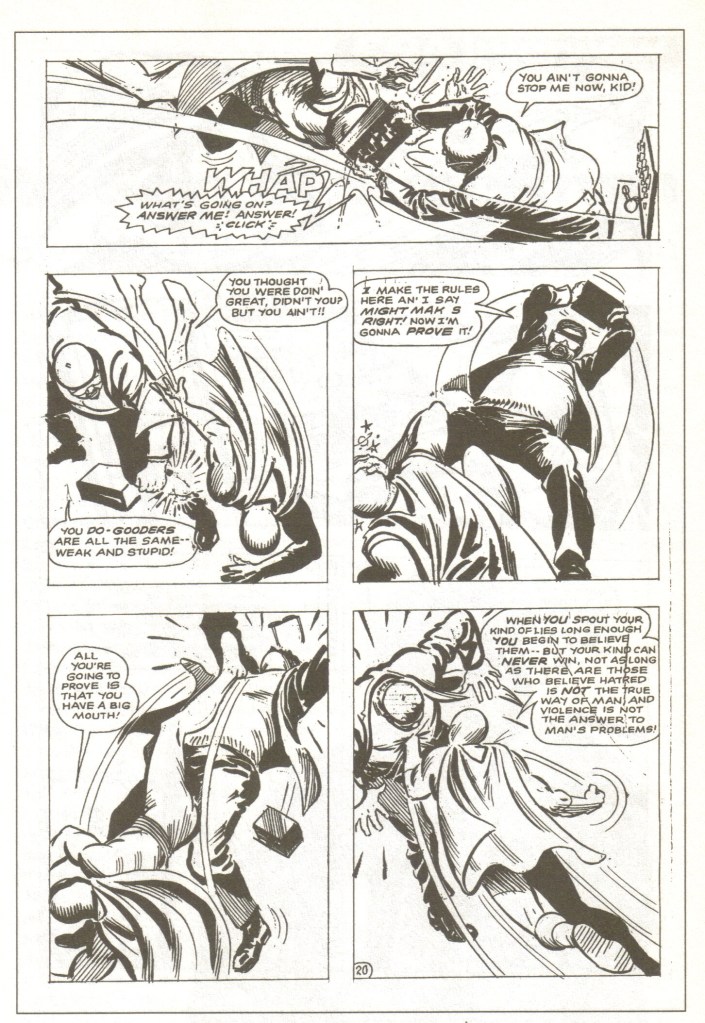

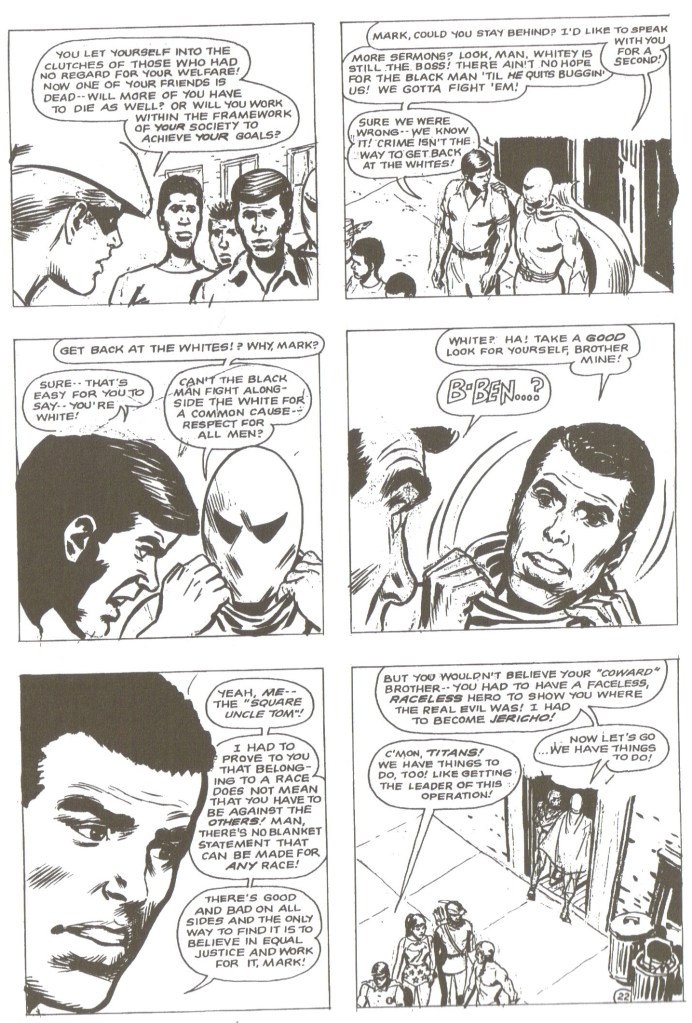

Editor Dick Giordano liked the idea and green-lit the pair to move ahead with a script. The trio also consulted with DC’s Editorial Director Irwin Donenfeld, the son of the firm’s founder Harry Donenfeld. Irwin was also positive about the potential of such a story, and advocated that it shouldn’t just be a one-off but rather a multi-part sequence. He saw the possibility for good press and an opportunity for DC to take back a bit of the spotlight from their growing rival, Marvel Comics, which had been written up in the press on a number of occasions as a more progressive publisher. Now, Wein and Wolfman were both young and new at their craft at this point, so the story they turned in, while well-intentioned, would eventually be criticised as being too much a polemic. Cries of reverse-racism were even thrown around. But for the moment, the story was a go. Wein and Wolfman delivered their script, editor Dick Giordano approved it and put it into production, and TEEN TITANS artist Nick Cardy began to draw it. He’d penciled the entire issue and had begun inking the job when the axe fell.

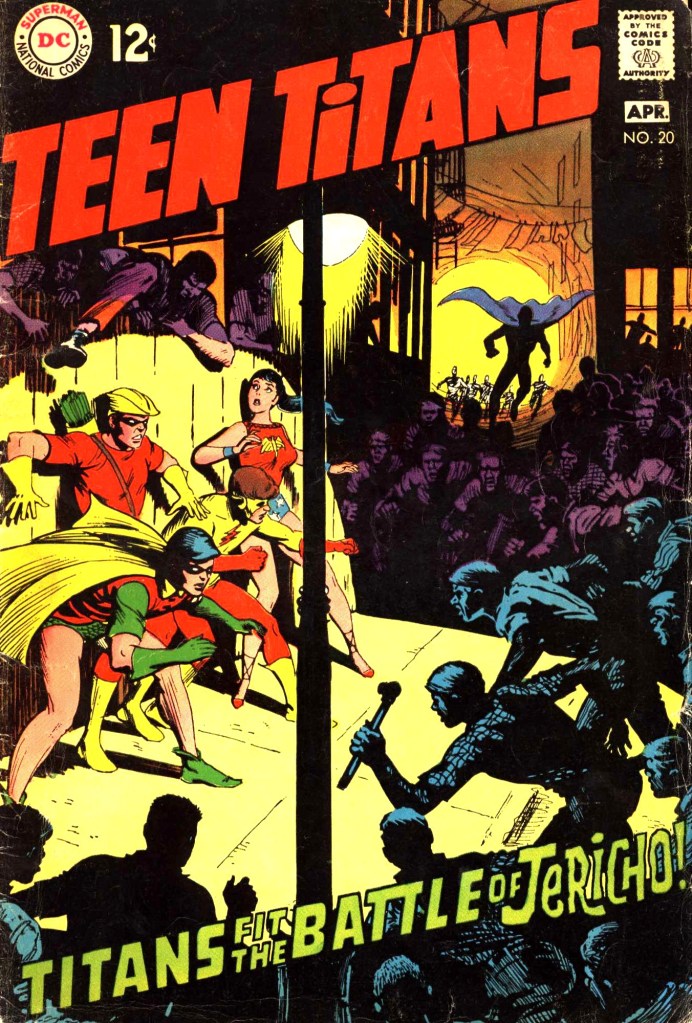

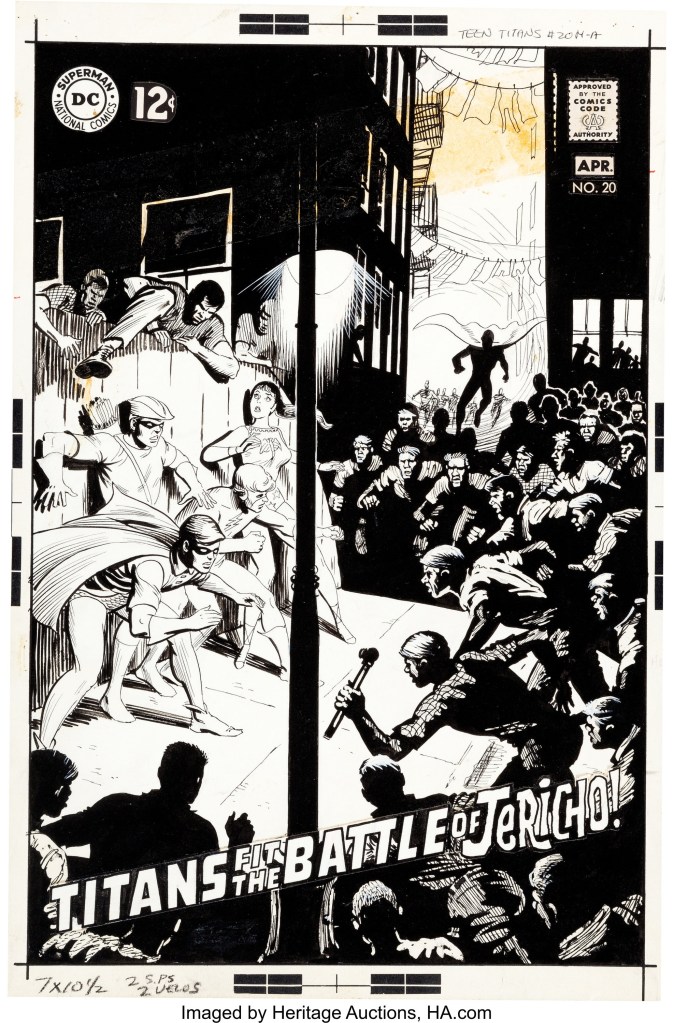

I’ve heard versions of this story told multiple times over the years, and everybody involved is a bit circumspect about pointing fingers. But privately, the situation surrounding this story is discussed a bit more directly. And it comes down to this; while this issue was in production, there was a changing-of-the-guard at DC. Irwin Donenfeld was let go as Editorial Director and replaced by Carmine Infantino, who had been working as the firm’s cover editor up until that time. Carmine is a storied artist whom nobody wants to speak badly of, and it’s debatable how much his decisions here were about his own feelings or his fears for the company should the story see print. At any event, becoming aware of the issue in progress, he asked Giordano to read it. And when he was finished, he told his editor that the book as it was then was unpublishable, not up to snuff and an embarrassment that DC would not print. Apparently, everybody involved in this initial conversation largely danced around the central issue; the fear that showcasing a black super hero would cost DC distribution in southern States. Nobody involved was happy about this sudden pronouncement, and apparently Wein and Wolfman in particular hit the roof and were very vocal about their position and beliefs. heated words were exchanged, and the pair was on the verge of being bounced out of DC by Carmine. Giordano had a more practical and immediate problem, however: he had to put an issue on press in about a week. In fact, the cover had already been sent to the printer, which meant that any replacement story that was done would have to still reflect it. Jericho was the proposed name of the new black character, so he title, “Titans Fit The Battle of Jericho” was emblazoned across the cover as copy. Apparently, the large mob of rioters had been colored as African-American on the version of the cover that was sent to print, so as a last-minute remedy, the printer was instructed to knock them all out in blues and purples so that no particular ethnicity would be evident. (or so the story goes–looking at the original art, those figures don’t look especially African-American to me.)

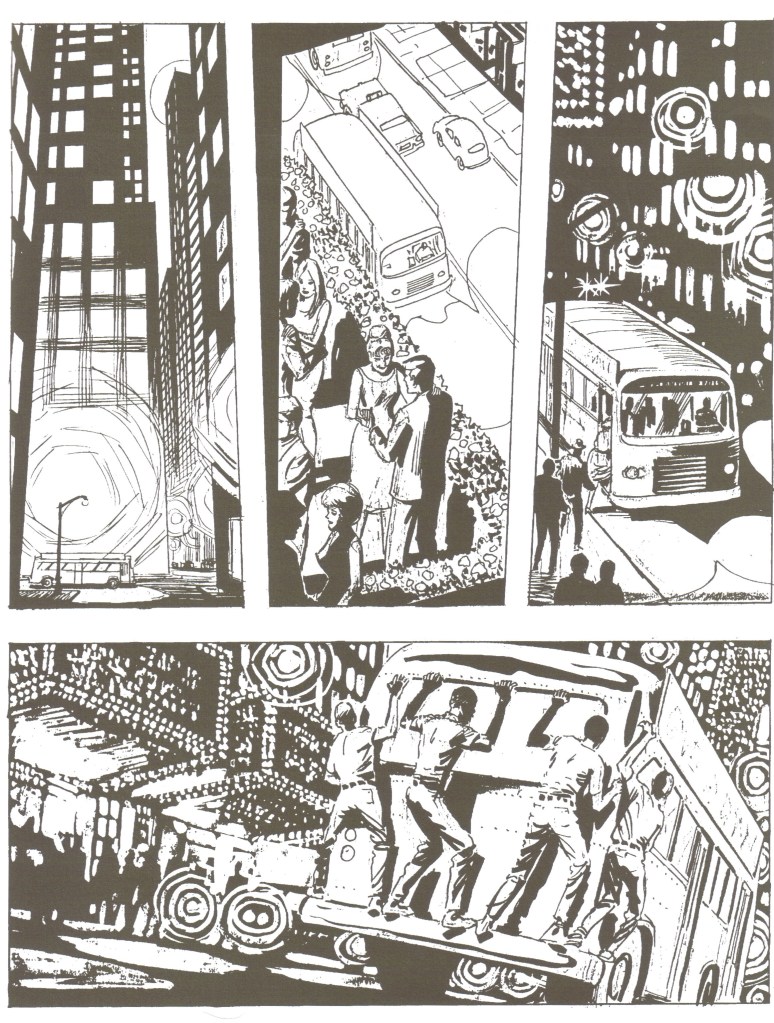

Both Giordano and the writers had an ally in the person of Neal Adams. Adams was a fair-haired figure up at DC in 1968, an artist who came in with an exciting new style and experience in real publishing, which meant he knew more about printing than many of the folks toiling away at DC. He was also a forward-looking voice and an advocate of young creators–someone who was listened to because of his own personality and his track record with sales and fan reaction. Wein and Wolfman approached Adams and asked him to read the story they’d done, claiming that management was being too conservative and asking for his help to salvage it. Neal read the book, and while he was sympathetic to its message, he didn’t think it was crafted well. But he was inspired to pull together a modified version of the story to present to Carmine, one that he would go into and fix with extensive redraws, bringing it into line. But Carmine would not hear of it. By this point, his back was up, and he wanted the whole thing spiked and Wein and Wolfman up against a wall. But now, Neal was involved, and Giordano still needed an issue that he could sent to print in a few short days. So Neal conceived an entirely new story, one without any black participants, which he penciled most of (a number of pages and panels from the aborted story were incorporated into it, partly in order to make it easier to get the issue done in the time left.) Nick Cardy was brought in to ink Neal’s pencils (really loose layouts in a lot of cases, so rapidly was this thing being thrown together.) Neal’s version replaced Jericho with a similarly-attired new super heroic character named Joshua, who also wore a largely stark-white costume. This replacement story came out and saw print without a ripple. But DC’s first black super hero would have to wait three more years until 1971–when Adams and writer Denny O’Neil would give Green Lantern’s power ring to African-American architect John Stewart for one memorable issue of GREEN LANTERN. It wasn’t until BLACK LIGHTNING #1 in 1976 that an African-American super hero appeared at DC with any manner of regularity.

“its dialogue rife with dated pseudo-slang indicative of what middle aged white men thought that teenagers sounded like.” Of course as a kid living in England at the time I had no reason to think they didn’t completely nail hip American slang.

Despite it’s goofiness, it’s a big plus to the book that Haney genuinely seems to like teenagers, even the guys comics usually made fun of (Drag racers, rock-and-rollers, hippies). And I’ve always liked his one-panel origin in the Titan’s first appearance — they realized teens need superhero help so they formed a teen, ’nuff said.

I imagine we’d have seen more of John Stewart if GL/GA had kept going.

LikeLiked by 3 people

I started reading comics around 1972/1973 and any pre-Rozakis Teen Titans (which was a hot mess itself) has been reprints. Due to the dialog and insane plots, it’s only the Cardy art I’ve ever enjoyed. I’ve always felt it was a travesty Cardy was never given a long run on a better book (and better chance at fame) than Aquaman or Teen Titans.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’ve seen the fear-of-the-South concern come up several times in the history of superhero comics, e.g. with the Legion of Super Heroes and the design of Ferro Lad and Shadow Lass. I can easily see a big conservative company being skittish. But was there ever a case of a big “Comics Code” company really losing distribution in the South because of the topic? I can’t claim any deep knowledge of the subtleties of Southern race relations. Having an African American hero actually join a “white” team might be a problem, as that would be integration. But I don’t think having a “white” team merely interact in a story with an independent African American hero violated the segregation system. Think of the Negro Leagues. Segregation meant people of different races couldn’t be on the same team, but different race teams were allowed to exist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What happened when Star Trek featured an interracial kiss tends to lend credence to the fear that even a Black guest star hero would be unwelcome.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And Charles Schulz’s editor freaked out when he had Franklin, black, going to the same school as Peppermint Patty.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interracial romance (well, close enough) was/is a very high level of Southern taboo. If the writers were proposing to have Jericho be Wonder Girl’s boyfriend, having them kissing on-panel, that would be an entirely different story. Franklin/Peanuts was about integration. But Jericho isn’t joining the team, or being anyone’s love interest. They aren’t even all going to ride a bus together. This seems to me much much less than those two items.

LikeLiked by 1 person

According to Wikipedia DC Comics’ other first African-American superhero Mal Duncan had his own controversial interracial kiss with fellow Teen Titan Lilith Clay that editorial director Carmine Infantino objected to thinking it was too controversial but editor Dick Giordano kept the scene, but coloured it in blue as a night scene, to draw less attention to the moment. Giordano recalls receiving many letters about the kiss, both hate mail ( including one death threat ( ME saying this — over fictional characters having a fictional kiss? )) and many supportive letters approving of the kiss. Mal Duncan 6 issues later [ Teen Titans#26 ( March-April 1970 ) ] replaces Joshua as an official DC Comics African-American superhero. Check out Wikipedia’s Kirk and Uhura Kiss to see all the original series Star Trek interracial kisses ( Uhura & Christine Chapel’s friendly kiss in “What Are Little Girls Made Of?” or “Space Seed” & “Mirror, Mirror”.

LikeLike

As unbelievable as it sounds, we were still dealing with “Fear of the South” in 2007. When I was in charge of Boom! editorial, we wanted to put out an excellent book by Geoffrey Thorne that was, essentially, the Black Sopranos. Some key stores down South (apologetically) told us that there was no way their customers would be interested, so we ended up having to spike the project over the financial losses we’d be taking. Ghuh.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Horrifyingly, I’d wager that if anything, the market in 2024 for anything smacking of social progress is even more inhospitable in broad swaths of this country.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So 1976 was when Black Lightning#1 ( April 1977 ) hit the newsstands, but Legion of Super-Heroes member Tyroc appeared in Superboy#216 ( April 1976 — by Cart Bates & Mike Grell ). Wikipedia says Mike Grell wasn’t a fan of his own co-creation ( Hence his costume ). DC Comics really dragged their feet on creating African or African-American Super-Heroes unlike Marvel: Black Panther [ FF#52 ( July 1966 )] & Falcon [ Captain America#117 ( September 1969 ) ]. Granted in the case of John Stewart ( as a Green Lantern – GL#87 ( December 1971-January 1972 ) ) they beat Marvel to an African-American hero with real power — Hero for Hire#1 ( June 1972 ),

LikeLiked by 1 person

CORRECTION, it seems I was wrong and Marvel also beat DC Comics to an African-American hero with real power: Tony Stark’s second Iron Man replacement boxer Eddie March [ Iron Man#21-22 ( January-February 1970 ) & 65-66 ( December-February 1973-1974 ) ] pre-dates John Stewart becoming a Green Lantern ( I wonder if Eddie March inspired John Stewart becoming a Green Lantern? Did John Stewart inspire Doctor Spectrum ( Dr. Obatu ) being revealed as an African in Iron Man#63 -66 ( October-February 1973-1974 )? Apparently Steve Perrin suggested Dr.Obatu on page of IM#63 –comics.org ). ( By the way I’m not counting MK-5 as African-American or African, just pointing out Aliens normally take on the appearance of Caucasians in comic books back then ) Alien robot Mechanoid Scout MK-5 ( a.k.a. Mike ) [ Iron Man#32 ( December 1970 ) befriended & fell in love with Belinda Thompkins – see profile at marvunapp.com ] assumed the appearance of an African-American male the way J’onn J’onzz the Martian Manhunter [ Detective Comics#225 ( November 1955 ) ] assumed the appearance of a Caucasian Male in his first appearance. The shape of Mechanoid Scout MK-5’s starship is in the shape of that star on Mar-Vell’s second uniform’s chest or almost the star on Nova’s helmet ( which only has 6 points vs. MK-5 starship’s 8 points ).

LikeLike

Prowler ( Hobie Brown ) [ The Amazing Spider-Man#78-79 ( November-December 1969 ) ]. Hobie Brown has a similar origin ( inventor whose invention was rejected ) as Taxi Taylor [ Mystic Comics#2 ( April 1940 ) –Wonder Car rejected by US government officials ] and 1 [ Captain America Comics#9 ( December 1941 ) Father Time story – Zarpo’s invention ( a bomb that would detonate after being near a human being for 5 minutes is turn down by the government as “silly” ) ] or 2 Timely Comics villains. Luckily Spider-Man was there to prevent Hobie from going the Zarpo route.

LikeLike

Timely Comics created a super-powered African-American hero Leander Jones ( magic gem using sorcerer father of Whitewash Jones ) [ Young Allies#10 ( Winter 1943-44 ) Young Allies 1st story ] and though the ones seen in flashback abused their power ( page 3 – which the head witch doctor of the tribes & great-grandfather of the witch doctor ( telling the story ) refused to give them more of the potion ) there was also African super-heroes [ Marvel Mystery Comics#26 ( December 1941 ) Ka-Zar story — ( Witch Doctor told Ka-Zar he only had a small amount of the powder left, but that could be a lie. Surely how to make the African Super-Soldier Serum was handed down the line of Witch Doctors ( page 2 -Centuries they had this potion ). Leander Jones is clearly a super-hero, showing up the way he did to battle supernatural menaces just like Doctor Strange in Fantastic Four#277 ( April 1985 ).

LikeLike

Atlas Age powerful African Witch Doctor name Moloo [ Marvel Tales#97 ( September 1950 ) 2nd story “Beyond the Grave” — The king of an African tribe is jealous the influence the witch doctor possesses, and so opens the cage of a captured gorilla that beast will slay the witch doctor ( who taken by surprise because he was sleeping and only managed to fire off an energy bolt that hit near his door ). The witch doctor transfers his mind into the creature during his final moments and returns later to slay the king. On the final panel the witch doctor in gorilla form is King Kong size with people running in terror ( Most of this is at comics.org and the rest from me cause I copied it on a USB & did email the pages to Marvel ]. To bad racists means he can’t stay in gorilla form, but since he is beloved by his tribe some might volunteer to let him borrow their bodies from time to time ( but combat might be in that gorilla’s body ).

LikeLike

I hope there is someone still alive to explain why it took till 1984 for Just-Us League to get members of real world human skin colour: Vixen [ Justice League of America Annual#2 ( October 1984 )]. Mal Duncan in the Teen Titans ( March-April 1970 ), Tyroc in the Legion of Super-Heroes ( April 1976 ), Tempest ( Joshua Clay )[ Showcase#94 ( August-September 1977 ) Doom Patrol II — Celsius ( Arani Caulder –from India ) ], Cyborg ( Victor Stone ) [ DC Comics Presents#26 ( October 1980 ) ], Northwind ( Norda ) [ All-Star Squadron#25 ( September 1983 ) Infinity Inc. member ] and Amazing Man ( Will Everett ) [ All-Star Squadron#27 ( November 1983 ) All-Star Squadron member ]. If something was stopping them from having a African-American in the JLA then what about an original American — a Native American Dawnstar [ Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes#226 (April 1977 ) ]. Cause Marvel didn’t implode from making the Black Panther an Avenger [ The Avengers#52 ( May 1968 ) ], Power Man ( Luke Cage ) a Defender ( 1975 ) & a member of the Fantastic Four ( FF#168-70 ( March-May1976 ) ), Storm ( African-American ), Thunderbird ( Native American ) & Sunfire ( Japanese ) members of the X-Men [ Giant-Size X-Men#1 ( May 1975 )] and the Falcon as an Avenger ( March (made ) & May ( appeared ) 1979 ). Shaman ( Aboriginal Canadian ) a member of Alpha Flight [ The X-Men#120 ( April 1979 ) ] & Karma, Psyche ( Dani Moonstar – Native American ) and Sunspot ( Brazilian )[ Marvel Graphic Novel#4 – The New Mutants ].

LikeLiked by 1 person

Looking back at JLA for a listicle I wrote, it was jaw-dropping to realize that yep, it took them 16 years to get a non-white human member. Super-Friends managed it on TV in the 1970s (and in the Super-Friends comics Global Guardians included black, Chinese, Japanese and Latin American heroes).

Marvl Wolfman and Len Wein had hoped to introduce a black superhero in Teen Titans around #20 but Infantino shot down the idea.

DC did better than Marvel on women characters, painfully bad on race.

LikeLike

TV reached a far wider audience than comic books. So, it makes sense better representation would happen there sooner. I’m not excusing it, but thinking of the circumstances.

LikeLike

Foolish, institutional stubbornness. Only in emergencies, like the “DC Implosion”, did DC seem to change at a faster pace than the old glaciers. (That comparison’s out of date, as glaciers are disappearing alarmingly fast.) I don’t know what the senior managers there personally thought about racial representation. But likely sales were most important (as almost always).

The JLA had been successful before by featuring their most popular or most powerful, established heroes. And they were all “white” characters, which was the historical precedent, based on a white majority in the general US population that was larger than it is today. “White privilege”.

And DC was slower to change than Marvel. Maybe Stan Lee was more open-minded in that regard, than his contemporaries at DC. Maybe Stan had more younger staffers around him. And racial bias/racism was absolutely a factor where comics were sold. There were just too many retailers in the US south that openly refused to sell comics featuring non-white, especially Black/African American hero characters.

That didn’t stop Marvel from advancing faster than DC. We could go back and forth. You’re right that most of the folks responsible for making those decisions are no longer working at DC, or even alive today. Maybe it’s more important to recognize where it can be improved on, now.

LikeLike

I think Stan Lee was able to change course and innovate as much because of Marvel’s structure as his creativity and talents. DC had editorial fiefdoms that traditionally did not work together and also didn’t act as if they were publishing a unified universe. If Lee had an idea, whether it proved to be successful or not, he only had Goodman to contend with.

LikeLike

Youth was definitely a factor, I think.

I’ve been rereading a lot of Silver Age stuff and the end of the Silver Age shows DC attempting something new as super-heroes foundered: teen-age Archie humor (Date With Debby, Binky), Anthro (stone-age teen), sword-and-sorcery (Nightmaster), Bat Lash. And of course, the horror anthologies which proved a winner.

Marvel in 1969 stepped into several genres it hadn’t been in for a while: love comics, horror anthologies, reprints of Harvey-type material such as Homer the Happy Ghost.

LikeLiked by 1 person