There is always one firm whose comic book output during the era we think of today as the Golden age of Comics stands head and shoulders above all others and which is held in teh utmost regard by those readers who encountered it in their formative years–not that there are many of those still around at this point. That was the titles published by EC COMICS as a part of their New Trend initiative–a move that saw them shifting their efforts towards horror, science fiction, war, crime and humor publications. Over time, the quality level of the company simply grew and grew–EC had the best artists and promoted them within their pages, and it was also the most literary-minded of any company of its day. But where did this all come from?

EC’s publisher Bill Gaines was the son of M.C. Gaines, himself a comic book publisher whose roots in the field extended back to the earliest efforts to create a comic book publication. M.C. is often credited as being the person who invented the format by folding a newspaper Sunday comic strip section in half. By 1949, Gaines had struck out on his own, and was eking a miniscule portion of the marketplace with his assorted lackluster titles–the crown jewel of which were his PICTURE STORIES FROM series that retold biblical and historic events in a form that children could absorb and understand. The name EC stood for Educational Comics, and it was a banner that M.C. Gaines stood behind.

But sadly, M.C. Gaines perished in a boating accident, leaving his company without a manager. At his mother’s request, son Bill Gaines came in to help run the business, even though he didn’t think he had any aptitude for it and his father thought he was something of a good-for-nothing. Bill was initially just showing up one day a week to sign the checks. But eventually, he began to take an interest in the form. This coincided with the moment when he first met artist Al Feldstein, who would prove to be an influential figure in the future of the company.

Feldstein was shopping for work, and he’d brought samples of a teen girl humor strip with him titled GOING STEADY WITH PEGGY. It didn’t end up being published by EC, but Gaines liked Feldstein’s drawings of pretty girls and the two men hit it off right away. So Gaines brought Feldstein on staff, and the pair began discussing the sorts of things that they liked, looking for something new to do in the field. Both men enjoyed the spooky horror radio shows of the era, which were typically hosted by a shadowy narrator and told creepy stories of murder, monsters and mayhem. The pair wondered whether such an approach might click with comic book readers.

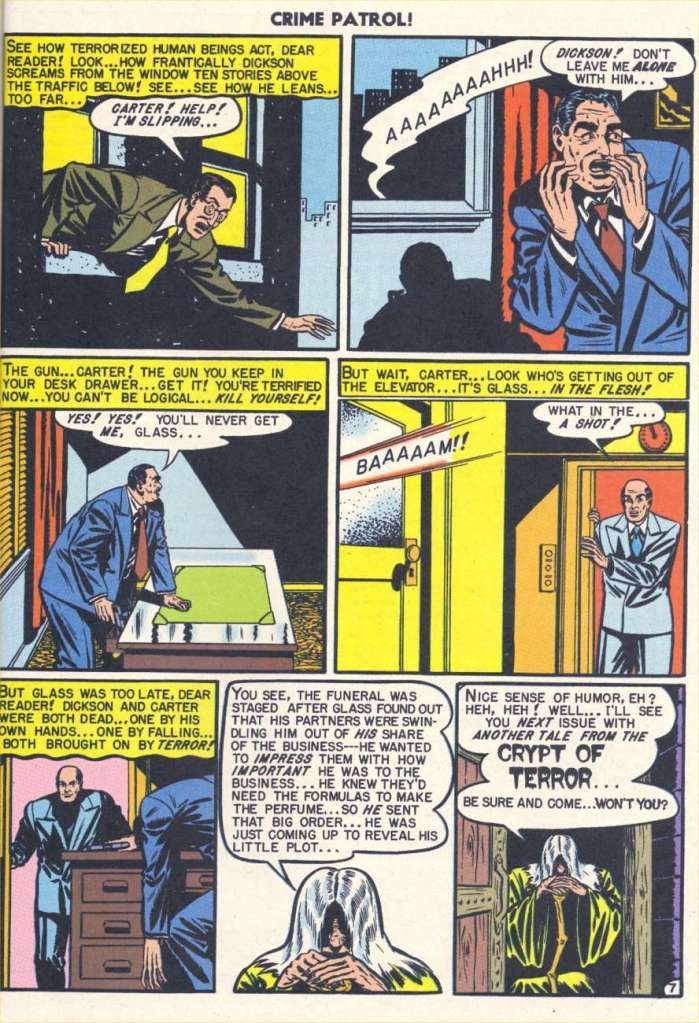

At the time, EC was publishing a routine crime series entitled CRIME PATROL. In its fifteenth issue, Gaines and Feldstein decided to try out their new idea. Nestled in the third story slot of four would be the prototype for the kind of story that would become EC’s bread and butter over the nest half-decade. It was cover blurbed as well in an attempt to bring some eyeballs to it. A second such story was created and ran in issue #16, both of them produced entirely by Feldstein with some conceptual input from Gaines. They called the strip THE CRYPT OF TERROR, and each story was introduced by the darkly humorous Crypt-Keeper.

This first story is really very sedate and bland as compared to the sort of material that EC would wind up producing across the next five years, but it must have struck a chord. It’s impossible to say whether the sales of CRIME PATROL skyrocketed or Gaines simply liked what they were doing, but by issue #17, the title had been renamed THE CRYPT OF TERROR, and Gaines and Feldstein commenced work on a pair of similar sister titles, THE HAUNT OF FEAR and THE VALUT OF HORROR. THE CRYPT OF TERROR would eventually be rebranded as TALES FROM THE CRYPT a short time later, and Gaines changed the name of the company, transforming it into Entertaining Comics.

While he continued to draw the occasional story and cover, over time Feldstein became the line’s chief writer and editorial voice, overseeing the work of a murderer’s row of artists that included Graham Ingles, Wally Wood, Jack Davis, John Severin, Harvey Kurtzman, Angelo Torres, Al Williamson, Johnny Craig and several others. At the height of production, Feldstein would write a full story every day, Monday through Thursday, composing them and tying them directly onto the art boards using teh mechanical Leroy Lettering process. From there, the artists were free to interpret the visuals in any manner they liked. Before too long, a competitive spirit pushed each creator to try to one-up his fellows, and the art became so detailed that many of the finer lines wouldn’t even show up in teh reproduction–they were simply there to impress the other guys.

EC became a casualty of the comic book witch-hunts of the 1950s that led to the creation of the Comics Code. The Code had been written in such a manner that it was practically targeting EC specifically, to drive them out of business. And it succeeded, but Bill Gaines had the last laugh. One of EC’s most popular titles was Harvey Kurtzman’s humor series MAD. At Kurtzman’s urging, Gaines transitioned MAD into a black and white magazine that was thus exempt from the demands of the Comics Code, and which, under Feldstein’s editorship after Kurtzman quit over a salary dispute, became a cornerstone of humor in teh American mainstream, and made Gaines very wealthy. Those classic EC books have been reprinted many, many times over the years since they vanished from the newsstands, such that the stories aren’t very difficult to come by today.

The captions and dialogue have a lot of the structure of a radio play here; you could have really lousy art and the strong story structure would still shine through. Maybe the better artists weren’t only competing with one another, but also with the written parts of the story; trying to see what they could bring forth that the words could not.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t say I ever thought of the EC era as Golden Age, despite its early-50s timeframe. It always felt to me like What Came Next, along with Barks Duck comics and LITTLE LULU, despite them too, starting up while the superheroes were ramping downward…

LikeLiked by 1 person

December 2nd this year will mark the centenary of Jack Davis, the longest-lived (and quite possibly the very best) of the EC artists.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This reads to me like the 1970’s DC “horror” stories, where the Code had relaxed enough to allow horror-lite, but the plots were still tame, plus the twists very forced. I almost expected the last panel to be something like “… and their deaths were UNEXPECTED” (the way that book’s theme was justified).

There’s too many plot holes here for me to enjoy the story. What did Glass expect his criminal partners to do when he showed up? I imagine they just might have thought, Glass has made sure everyone thinks he’s dead, so let’s get the formulas from him, and then make it a reality.

LikeLike

I wish I had thought of this Sunday ( Googling EC Comics — wikipedia )– Tom Forgot THIS: Noted for their high quality and shock endings, THESE STORIES WERE ALSO UNIQUE IN THEIR SOCIALLY CONSCIOUS, PROGRESSIVE THEMES ( INCLUDING RACIAL EQUALITY, ANTI-WAR ADVOCACY, NUCLEAR DISARMAMENT, and ENVIRONMENTALISM ) THAT ANTICIPATED THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT and the DAWN OF THE 1960S COUNTERCULTURE. Plus this STORY: Gaines battle with a racist Comics Code Administrator ( Judge Charles Murphy ) over “Judgment Day” [ Incredible Science Fiction#33 ( February 1956 ) by Al Feldstein and Joe Orlando ( a reprint from a pre-Code Weird Fantasy#18 ( April 1953 ) ] –The story depicted a human astronaut, a representative of the Galactic Republic, visiting the planet Cybrina, inhabited by robots. He finds the robots divided into functionally identical orange and blue races, with one having fewer rights and privileges than the other. The astronaut determines that due to the robots’ bigotry, the Galactic Republic should not admit the planet until these problems are resolved. In the final panel, he removes his helmet, revealing he is a BLACK MAN. ( Murphy demanded, without any authority in the Code, that the Black astronaut had to be removed. There is more to the story but it ends with Gaines telling Murphy, “Fuck You’. )—This story reminds me of the Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode Far Beyond The Stars ( 1953 sci-fi writer Benny Russell for Incredible Tales — we can’t have a Black Man running a Space Station, change it ).The plagiarized Ray Bradbury Stories & that evil little man Dr. Fedric Wertham was recreated ( Brad Rayberry, Mr. Feldstone & Dr. Werthers ) in the final season of CW’s Riverdale where Pep Comics was a stand-in for EC Comics.

LikeLiked by 1 person