This issue of MARVEL TALES presented me with a slightly more manageable conundrum. I didn’t own a copy of AMAZING SPIDER-MAN #124, the issue that was reprinted here, but I had read it. I believe my school buddy Don Sims had a copy, and I’d read it at his place at some point. Consequently, this issue would hold very few surprises for me. But it was still a relatively simple choice to drop 35 cents on it. After all, I didn’t own the issue in question, Don did.

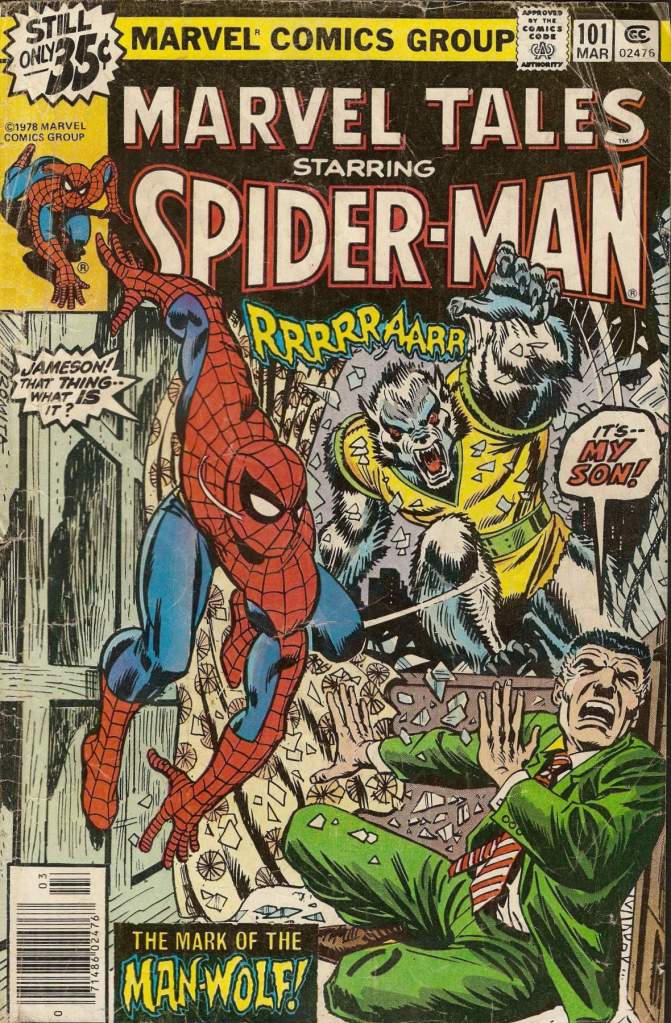

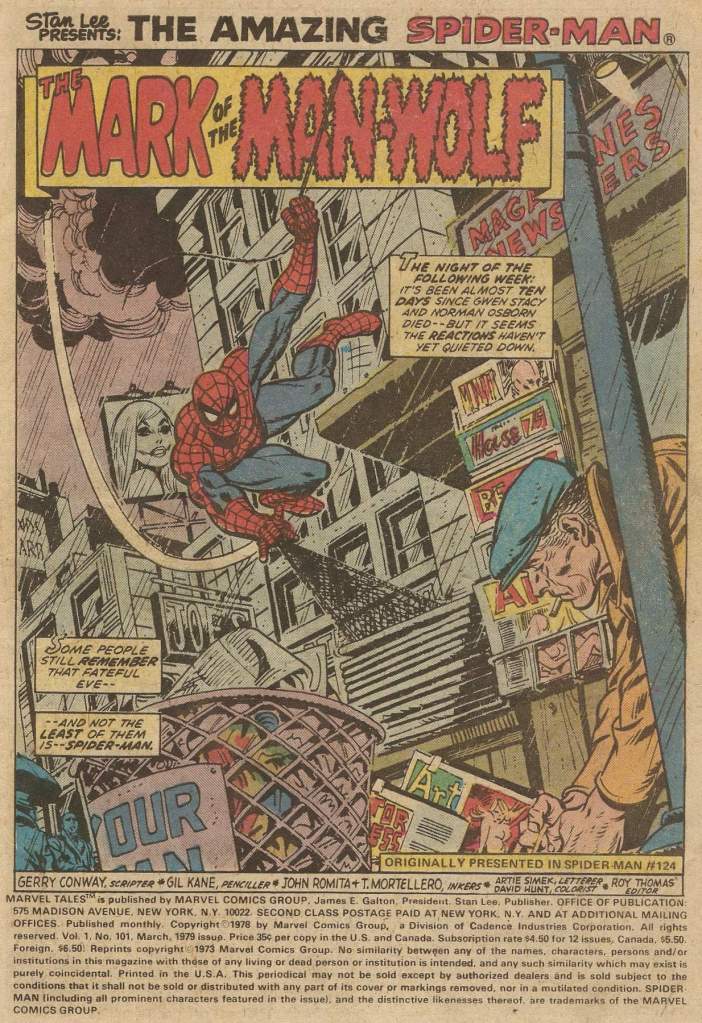

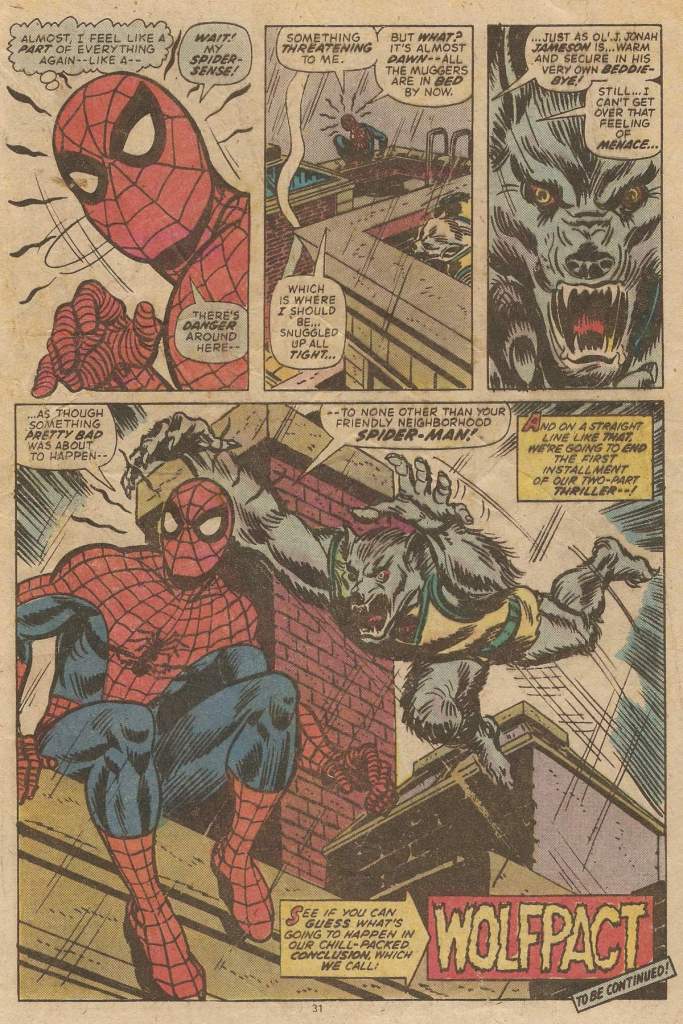

We were right at the pivot-point where the Silver Age had transitioned into the Bronze Age. Stan Lee had handed over the scripting to newcomer Gerry Conway, and John Romita was about to relinquish his long stint co-plotting and keeping the visuals consistent. While this issue was penciled by Gil Kane, Romita took a strong hand in the inking to keep everybody and everything on model. It was a lot of work, but the final look is excellent, combining Kane’s lithe action with Romita’s attractive characters and finish. As much as anything, this is what I think of when I imagine the look of Spider-Man, especially in the post-Ditko period.

This story was just two issues after Gwen Stacy and the Green Goblin were both killed, and their loss hangs over Peter Parker like a pallor. The Daily Bugle is still making headlines casting blame towards Spider-Man for the twin homicides, and while Peter is trying to get back to his usual college routine, all he can think about is the pitying stares from the rest of the students and faculty. He’s only barely holding his life together at this point, and he blasts both Mary Jane Watson and Flash Thompson when they turn up to give him sympathy. This very much became Peter’s characterization for the next couple of months. He was often volatile and abusive to his friends and family .

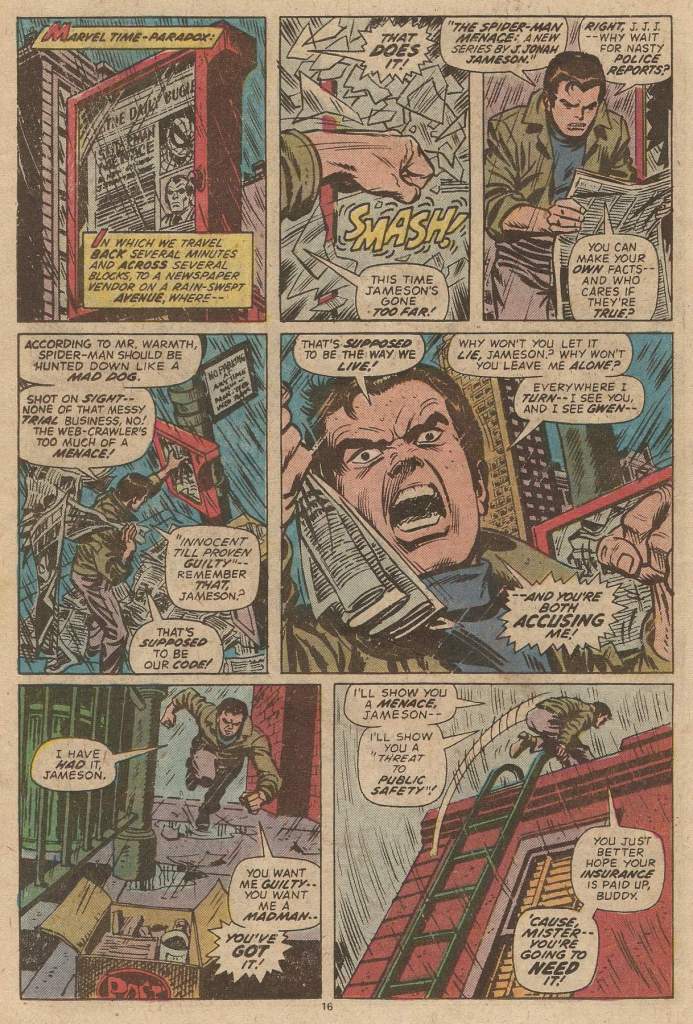

Finally, Peter reaches his breaking point after seeing yet another Daily Bugle editorial taking him to task. He loses it, smashing up the newsbox and making a beeline for Jameson’s apartment intent on kicking the crap out of him. This is definitely not a super hero in a good frame of mind. But there is something good that comes of this. Because prior to this moment, we’ve seen Jonah’s son, astronaut John Jameson, transform into a lupine creature called the Man-Wolf. John’s in town to introduce his father to his fiancée Kristine. But something is clearly wrong with John, and after metamorphosizing, he too heads out in the direction of Jameson’s building, following some instinct to find his father.

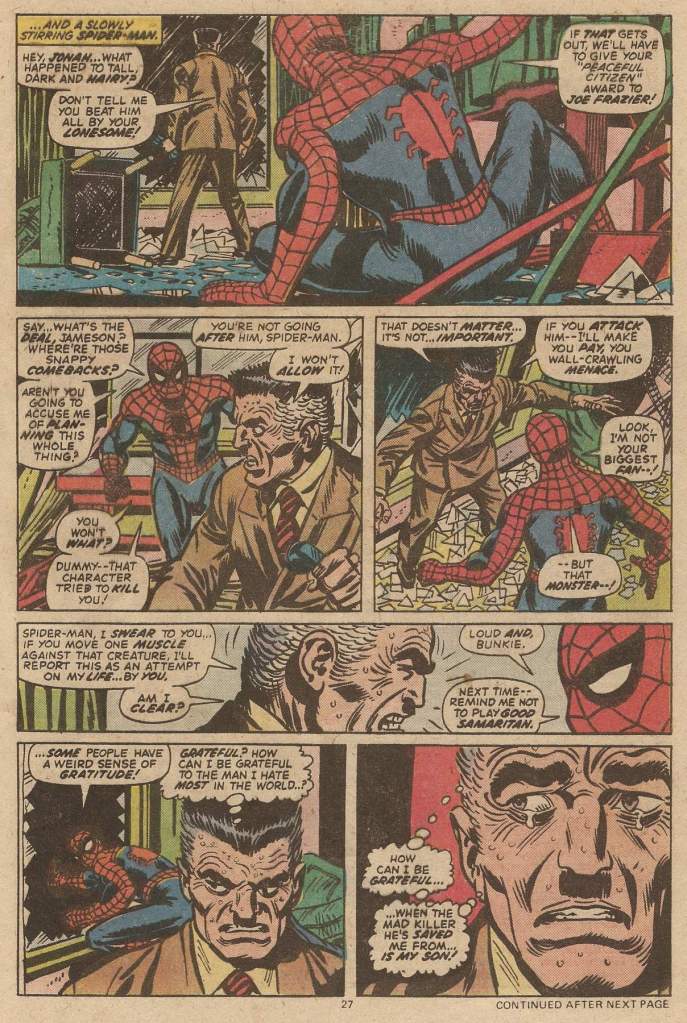

All of which means that Spider-Man shows up just in time to save Jameson from the savage attack of the Man-Wolf. This was a period shortly after the Comics Code had relaxed some of its restrictions on depicting classic monsters, and Marvel was going all-in on establishing a line of monster-based horror/adventure comics. The Man-Wolf was created as a part of this effort, a character like the previous Morbius who could straddle the line between the super hero titles and the monster ones. In any event, despite his frustrations with Jameson, Spidey can’t stand by and let him be killed, so he throws himself into a pitched battle with the Man-Wolf.

Spidey has been spoiling for a fight, and a clash with a mute werewolf who is clearly a monster gives him a justifiable target for his aggression. But ultimately, Spider-Man is fighting sloppy, and he winds up taking a blow to the head that momentarily stuns him. While he recovers, the Man-Wolf shares a wordless moment with Jameson before fleeing from the building. Spidey recovers enough to go after the Man-Wolf, but Jameson forbids it and threatens to blame this attack on the wall-crawler if he doesn’t relent. So Spidey stalks off, irritated and unfulfilled, and we see that Jonah has recognized the Man-Wolf as his son John, and is trying to protect him.

And as the issue wraps up, Spidey decompresses for a moment on a rooftop, reflecting on the fact that his fight with the Man-Wolf did him some good, allowed him to release some of his pent-up frustrations. He feels more like his usual self again for the first time in a while. But then his spider-sense begins to buzz, as the man-Wolf lunges to attack him. To Be Continued! The feeling of heightened soap opera drama and operatic emotional expression were hallmarks of the series in this era, and its urban Manhattan setting and grounded approach–even factoring in for a werewolf–made Spider-Man seem a lot more plausible and realistic than the typical super hero series. These qualities would ebb and flow across the decade and into the next, but I think they were a lot of the heart of the book’s appeal in this era.

Romita co-plotting?

“The only thing he used to do from 1966-72 was come in and leave a note on my drawing table saying “Next Month, the Rhino.” That’s all; he wouldn’t tell me anything; how to handle it.” – John Romita, Comic Book Artist #6 Fall 1999.

Sounds like Romita was also writing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Plotting it, yes. Stan still wrote the dialogue.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Weird…

If an Editor at DC said, “Hey, why not bring back Solomon Grundy this issue” to an artist, who then plotted out the story, and… let’s face it, WROTE the story through the artwork and the editor then came in and put the dialogue in afterwords… that artist would also be the WRITER (and paid as such) and the editor would be credited as ‘dialogue’.

It’s a shame John Romita will never be credited with (or paid for) an awful lot of stories he actually wrote or created basically from scratch. Without a synopsis, without any direction other than, IN HIS OWN WORDS, Stan saying, “Next month, the Rhino”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“If an Editor at DC said, ‘Hey, why not bring back Solomon Grundy this issue’ to an artist, who then plotted out the story, and… let’s face it, WROTE the story through the artwork and the editor then came in and put the dialogue in afterwords… that artist would also be the WRITER (and paid as such) and the editor would be credited as ‘dialogue’.”

No, the artist would be credited as the plotter, and the editor would be credited with dialogue. They could be credited as co-writers, but dialogue is part of writing.

“It’s a shame John Romita will never be credited with (or paid for) an awful lot of stories he actually wrote or created basically from scratch.”

Yes, it is. And it is for Kirby, for Ditko before he demanded plot credit, for Don Heck, Gene Colan, Al Hartley, Stan Goldberg and many more.

But it’s worth getting the credits right. Plotting a story is part of writing it, but both plotter and scripter should get proper credit.

LikeLiked by 2 people

>>>KURT: I hope you’ll entertain the idea, at least, that I’ve got 42 years of experience as a professional comics writer (and even occasional editor) and know what constitutes plotting, scripting and editing. So when I tell you that writing dialogue is not editing, I’m speaking from a firm knowledge of how things work.<<<

You’re debating what went in on in YOUR way of working, in a more modern era of the business. I’m talking about the Marvel Method, which wasn’t created to ‘collaborate’, but rather… well, I won’t even go there for Tom’s sake.

With all due respect to your 42 years in the business, you’ll never convince me that Stan Lee didn’t dumb down Kirby’s stories, in particular the HIM storyline. Stan’s idea of what was good, wasn’t progressive at all – that came from others – he saw females as passive – fainting when trouble started or needing to be saved. That’s an editorial decision.

I’ll take New Gods over most of it any day.

I’ve read every book Kirby and Lee did from 1954 to 1964, just recently – IN ORDER – and it’s very plain to see. Even at Marvel, the quality of STORY varies wildly when reading something Kirby was 100% invested in, vs a Don Heck/Stan Lee story or a Dick Ayers/Stan Lee story.

There’s a reason the Marvel Method was created, and it had nothing to do with ‘Collaboration’. But that’s a topic for elsewhere.

LikeLike

“You’re debating what went in on in YOUR way of working, in a more modern era of the business.”

No, Chuck, I’m not. I’ve used examples from the 60s to recently.

“I’m talking about the Marvel Method, which wasn’t created to ‘collaborate’, but rather…”

It absolutely was created to collaborate. And if the credits had been accurate and the payments fair, it’d be a reasonable way to work — get the creative genius to do the plots, write snappy dialogue over it.

Stan made it appear as if he did work that his collaborators were doing, and that was bad. But the idea of having one guy plot and draw and another guy script, there’s nothing inherently wrong with that.

“I’ll take New Gods over most of it any day.”

Me too, but I’ll take KAMANDI over either.

Vaya con carne, Chuck.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“You’re debating what went in on in YOUR way of working, in a more modern era of the business.”

And to add: When you say it’s not a plot it’s a story, and I say that in comics it’s called a plot, that’s what I’m talking about when I say I know what I’m talking about. It’s called a plot today, in my way of working, but it was called a plot back then, too — just look at the credits to STRANGE TALES and AMAZING SPIDER-MAN after Ditko demanded credit. He’s credited with plotting and art. So yes, that was the industry term back then, too, no matter how much you want to insist it’s not so.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for choosing to have this conversation, Kurt.

>>>No, the artist would be credited as the plotter, and the editor would be credited with dialogue. They could be credited as co-writers, but dialogue is part of writing.<<<

Yet… he couldn’t write the story without knowing what the characters thoughts, motivations, and… what they were saying. The ‘dialogue’ person is simply interpreting what the artist has already essentially WRITTEN.

That ‘dialogue’ COULD add to it, or NOT… the ‘dialogue’ person could simply follow along with whatever the artist said… I still see this as the ARTIST was the writer. He began with a blank page, knowing who the cast was, and maybe a name for a villain – and no more – and WROTE the story.

Someone adding stylized dialogue to it is no different than what many editors throughout comics do on a regular basis.. take a creators story and make corrections to grammar – continuity – or just spice up some dialogue that they think sounds better. They don’t get a co-plotter credit for that.

>>>Yes, it is. And it is for Kirby, for Ditko before he demanded plot credit, for Don Heck, Gene Colan, Al Hartley, Stan Goldberg and many more.<<<

At least we’re seeing a little MORE of it…

>>>But it’s worth getting the credits right. Plotting a story is part of writing it, but both plotter and scripter should get proper credit.<<<

See you changed that to ‘scripter’. But the story has already been written, when the ‘dialogue’ person puts the words in. A plot is the outline to a story. There IS no plot before the artist WRITES the story. The dialogue doesn’t necessarily ADD to the plot. And yet, it’s credited as Writer and Artist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If a story consisted of only the plot, there would be no real characterization which is conveyed through dialogue. The same actions, even with notes from the artist, take on a different tone when the person speaks in a specific dialect or vocabulary.

LikeLike

CHUCK: Yet… he couldn’t write the story without knowing what the characters thoughts, motivations, and… what they were saying. The ‘dialogue’ person is simply interpreting what the artist has already essentially WRITTEN.

ME: You keep saying “written” as if plotting is all there is to writing.

The artist has written the plot, yes. The scripter then writes the captions, dialogue, thought balloons, etc. It would be wrong to credit only the scripter as full writer, but it would also be wrong to credit only the plotter.

The script may also alter what the plotter intended, giving the characters different thoughts, motivations, etc. Both Jack Kirby and John Byrne got very frustrated by that, at times, but it’s nonetheless true.

So dialogue can deliver on the plotter’s intent, add to it, alter it…it’s a collaborative part of the whole.

This is true even when the plotter and writer are the same person. When I write a plot, the artist interprets it while telling the story visually, and I may find, when responding to the art while scripting, that I want to change my own intent. It’s not finished until it’s finished.

CHUCK: I still see this as the ARTIST was the writer.

ME: I know. But while it’s accurate to say the artist is a writer, it’s inaccurate to say the artist is the writer. And the claim that DC would credit an artist/plotter as WRITER while crediting the scripter as DIALOGUE simply isn’t true.

To pick the 1970s run of SHADE THE CHANGING MAN, plotted by Steve Ditko and scripted by Michael Fleisher, for a handy example, Ditko is credited with “story” once, with the line “created, drawn and plotted by” once” and “concept and art” the other 5-6 times. He’s never credited simply as “writer.”

[Me, I think “concept and art” is a bad and misleading credit, because “concept” doesn’t imply plot, just an idea. But since it was used so steadily, I have to think it’s what Ditko insisted on.]

When Keith Giffen was doing plot and layouts for JUSTICE LEAGUE and Marc deMatteis was doing dialogue, Keith was credited with “plot & breakdowns” and Marc with “script.”

When Jim Starlin plotted SUPERBOY/LEGION 239, the credits read “Jim Starlin, plot-layouts / Paul Levitz, dialogue-plot assist.”

Aside from this being counter to your claim, it’s also accurate. We can read that and know what each of them did.

CHUCK: Someone adding stylized dialogue to it is no different than what many editors throughout comics do on a regular basis.

ME: Can you provide an example of this? Because I’ve been a comics pro for over 40 years, and editors adding all the dialogue to blank pages, uncredited as co-writer, is not something I’ve ever seen, much less on a regular basis.

CHUCK: …take a creators story and make corrections to grammar – continuity – or just spice up some dialogue that they think sounds better. They don’t get a co-plotter credit for that.

ME: We’re not talking about co-plotting credit, but co-writing credit. You’re claiming the plotter is the sole writer and the dialogue writer is just editing. That’s not true.

OLD ME: But it’s worth getting the credits right. Plotting a story is part of writing it, but both plotter and scripter should get proper credit.

CHUCK: See you changed that to ‘scripter’.

ME: It’s the credit most often used to describe the job. Credits can be difficult to sum up in a word or two. Sometimes script means a full script, sometimes it means the lettered text — captions, dialogue, thought balloons, SFX. Sometimes story means plot, sometimes it means the whole job. “Dialogue” is a shorthand, but it refers to more than just dialogue.

But in a situation where there aren’t perfect terms, “Plot” and “script” are the most common used to describe those jobs.

CHUCK: But the story has already been written, when the ‘dialogue’ person puts the words in.

ME: No, the plot’s been written. But the writing isn’t finished until you have both plot and script.

CHUCK: A plot is the outline to a story. There IS no plot before the artist WRITES the story.

ME: In the situation you’re referring to, that’s correct, though I’d replace “writes the story” with “writes the plot,” for clarity. But while there’s no plot when Romita started work, there’s also no finished, fully-written comic when he finished drawing it, unless it’s a silent story.

CHUCK: The dialogue doesn’t necessarily ADD to the plot. And yet, it’s credited as Writer and Artist.

ME: The dialogue adds to the writing. And if the artist plotted the story, it should be credited accurately: JOE PENCILS, Plot & Art / FRED KEYBOARD, Script.

Even if you don’t think the scripter added much, you at least know who did what, when you read credits like that. To call Stan the sole writer would be wrong. To call John the sole writer would be wrong. To call John the plotter and Stan the scripter is both accurate and clear.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“If a story consisted of only the plot, there would be no real characterization which is conveyed through dialogue.”

Pat, you know better than that. Or at least I hope you do.

Characterization is conveyed through behavior, as well as dialogue. A comic with no characterization in the art would be very bad. Characterization is in body language, facial expressions, actions, reactions and more. It can also be in dialogue, but there’s characterization in silent comics. There’s characterization in moments where what the art shows and what the dialogue says contradict each other, and in those cases it’s rarely what the dialogue says.

The idea that there’s no real characterization without dialogue is a sweeping misunderstanding of not just comics, but movies, stage drama, even prose.

LikeLiked by 1 person

>>>KURT: You keep saying “written” as if plotting is all there is to writing.<<<

ME: First of all, I think we both agree that the artist didn’t get enough credit with how the system worked (or paid correctly, in the case of guys like Kirby and Ditko)

But I think you’re misinterpreting what plotting and writing is and believe me… I feel weird saying that to a WRITER. Maybe I mean ‘misinterpreting what I BELIEVE is plotting and writing’… that’s better…

When I first read Arzach in Heavy Metal #1, I got to the end of Moebius’ story and realized… there was no dialogue. Yet I followed and understood that story from beginning to end. It really opened my mind about comics…

When John Romita sat down with a blank page, and his only guide was ‘This month the Rhino”, he then WROTE a story with his art. He had to decide… does this begin at the Daily Bugle, does this begin with Spidey on a random rooftop, is it raining, does he have a sprained arm still from last issue, does any of this play into how I’m going to END this issue, etc. etc.

He didn’t just draw a bunch of random stuff and give it to a writer and go, “Here, figure something out.”

He WROTE a STORY through his art. That’s NOT just a plot.

Does it need dialogue to make it complete?

Dick Ayers did a whole story with no words once and it still got printed just fine. (Stan was still listed as the ‘writer’ even though he didn’t write anything…)

There’s plenty of examples of Comic Book stories not having dialogue. Yeah, it’s an exception much more than the rule, but… the truth is… with art, the story can still BE there, even without the words written in yet.

>>>KURT: The artist has written the plot, yes. The scripter then writes the captions, dialogue, thought balloons, etc. It would be wrong to credit only the scripter as full writer, but it would also be wrong to credit only the plotter. The script may also alter what the plotter intended, giving the characters different thoughts, motivations, etc. Both Jack Kirby and John Byrne got very frustrated by that, at times, but it’s nonetheless true.

So dialogue can deliver on the plotter’s intent, add to it, alter it…it’s a collaborative part of the whole.<<<

ME: Two things here. Usually, when the ‘dialogue person’ (I still can’t wrap my head around ‘scripter’ for that job), makes changes to the intent… MOST of the time… especially in the Kirby and Byrne cases, it had to do with SIMPLIFYING or keeping things within an agreed upon HOUSE STYLE… I.e. it was EDITORIALIZED.

Byrne actually WROTE the dialogue and had it changed – that’s not collaboration – that’s editing.

Kirby used to write the dialogue into the panels and Stan made him stop, simply because HE wanted the credit (and pay) for it. Again, anything that Stan changed was done for what was, in HIS opinion, the better and more simplified version of the story to reach a larger audience.

I don’t know many great artists who would see that as COLLABORATIVE.

(Please don’t take offense to the capitalized words… it’s for emphasis – not yelling 🙂 )

>>>KURT: This is true even when the plotter and writer are the same person. When I write a plot, the artist interprets it while telling the story visually, and I may find, when responding to the art while scripting, that I want to change my own intent. It’s not finished until it’s finished.<<<

ME: But the artist in that situation is starting the process WITH a real plot. The collaboration is true from the beginning. I don’t think it was always that way with Kirby, Ditko, and, from what Romita has said, even himself.

>>>CHUCK: I still see this as the ARTIST was the writer.

KURT: I know. But while it’s accurate to say the artist is a writer, it’s inaccurate to say the artist is THE writer. <<<

Mmmm… I don’t know. He came up with the story in the first place. Kirby’s Silver Surfer was a STORY in FF #48, and Stan knew nothing about it. That wasn’t a PLOT. It was a STORY. Regardless of if Stan used certain words or not, the STORY was already there.

>>>KURT:And the claim that DC would credit an artist/plotter as WRITER while crediting the scripter as DIALOGUE simply isn’t true.<<<

ME: No no, that’s wasn’t what I meant… the Editor changing words would never even be seen as ‘dialogue’. He was simply doing what an editor does and shoring up the work.

>>>CHUCK: Someone adding stylized dialogue to it is no different than what many editors throughout comics do on a regular basis.

KURT: Can you provide an example of this? Because I’ve been a comics pro for over 40 years, and editors adding all the dialogue to blank pages, uncredited as co-writer, is not something I’ve ever seen, much less on a regular basis.<<<

ME: Again. Not quite what I meant. Stan CREATED the concept of the Editor making the artist NOT write the words, so that HE could. That way he’d get the credit (as writer) and thus the PAY. He could’ve let Kirby do his own dialogue, still made his subtle changes (and there are some examples of him doing this from Kirby’s margin notes) and simply been the Editor. He CHOSE to do that dialogue for very specific reasons. Credit and Pay.

I’m sure over the years Julius Schwartz got plenty of stories that were… not done as well as they should’ve been and had to put some time in to clean up the dialogue and sort things out. He never considered himself the writer or co-plotter because of it.

>>>Even if you don’t think the scripter added much, you at least know who did what, when you read credits like that. To call Stan the sole writer would be wrong. To call John the sole writer would be wrong. To call John the plotter and Stan the scripter is both accurate and clear.<<<

I wouldn’t emphasis SOLE writer for the artist… but I think he IS the writer. Anything added from the dialogue that’s a change, would be Editing. Really it should read John Romita: Story and Art, Stan Lee: Dialogue and Editing. THAT, I believe is a lot more truthful.

I appreciate the conversation, but I don’t think we’re going to sway each other’s thoughts on it any…! But hey, it’s fun to discuss…

LikeLiked by 1 person

If you can’t accept that writing involves words and plotting and drawing does not, then yes, there will be no convincing you.

LikeLike

CHUCK: First of all, I think we both agree that the artist didn’t get enough credit with how the system worked (or paid correctly, in the case of guys like Kirby and Ditko)

ME: Yes.

CHUCK: When I first read Arzach in Heavy Metal #1, I got to the end of Moebius’ story and realized… there was no dialogue. Yet I followed and understood that story from beginning to end. It really opened my mind about comics…

ME: Sure. Moebius wrote that story; he wrote all of it. He’s the writer; no one else was involved. This is also true of the stories he wrote where he included dialogue.

CHUCK: When John Romita sat down with a blank page, and his only guide was ‘This month the Rhino”, he then WROTE a story with his art. He had to decide… does this begin at the Daily Bugle, does this begin with Spidey on a random rooftop, is it raining, does he have a sprained arm still from last issue, does any of this play into how I’m going to END this issue, etc. etc.

ME: Yes. What he did was writing. It’s just not the whole of the writing job.

CHUCK: He WROTE a STORY through his art. That’s NOT just a plot.

ME: Yes it is. It’s not intended to be wordless. It’s not complete, unlike Arzach.

CHUCK: Does it need dialogue to make it complete?

ME: Yes. If you take Romita’s issues of AMAZING SPIDER-MAN and take out the words, what you have left isn’t a finished comic. It needs words.

CHUCK: Dick Ayers did a whole story with no words once and it still got printed just fine. (Stan was still listed as the ‘writer’ even though he didn’t write anything…)

ME: Yeah, that’s discrediting. If Ayers plotted a silent story on his own, then he’s the writer of that story.

CHUCK: There’s plenty of examples of Comic Book stories not having dialogue. Yeah, it’s an exception much more than the rule, but… the truth is… with art, the story can still BE there, even without the words written in yet.

ME: It can. But that doesn’t mean it always is.

Take AVENGERS 49, for instance. It’s a silent issue. I plotted it — panel by panel — and Kieron Dwyer drew it. It was designed to be wordless.

But AVENGERS 48 wasn’t designed to be silent, and if we didn’t have anything lettered, readers wouldn’t get a story out of it. It wouldn’t be finished.

So saying that comics can be wordless doesn’t mean that all comics are finished stories even before they’re scripted. Comics designed to be wordless are. Comics that aren’t…aren’t.

CHUCK: Two things here. Usually, when the ‘dialogue person’ (I still can’t wrap my head around ‘scripter’ for that job), makes changes to the intent… MOST of the time… especially in the Kirby and Byrne cases, it had to do with SIMPLIFYING or keeping things within an agreed upon HOUSE STYLE… I.e. it was EDITORIALIZED.

ME: That’s not true at all.

In the case of Kirby, I’m thinking of the “Him” story, where Stan altered the theme of the story, changing the “Enclave” characters from well-meaning scientists who create an amoral creature to them being evil scientists who create a saintly creature. That wasn’t simplifying anything, or keeping it to house style. That was alteration of the intent, because Stan wanted the story to be something else.

In the case of Byrne, he was annoyed that he’d draw the story from a discussion with Claremont (or sometimes less) and include a scene that he’d specify was all in red, because it was seen through the Wendigo’s POV, and Chris would script it so that the red was the sunset. Or that John would draw a panel where Wolverine’s supposed to be making a point, and Chris would give Wolverine two words and have a balloon from some off-panel character saying something very different. That, too, is not simplifying or keeping to a house style.

I’ve done this myself, when working with an artist who drew things at odds with what I’d wanted — I’d finesse the dialogue to repurpose what they drew so that what I wanted was back on the page. Trust me, I wasn’t editing. I was writing. Collaborating, not necessarily smoothly, but it’s collaborative.

CHUCK: Byrne actually WROTE the dialogue and had it changed – that’s not collaboration – that’s editing.

ME: No, he didn’t. When John was drawing X-MEN in the 70s, he didn’t write the dialogue.

CHUCK: Kirby used to write the dialogue into the panels and Stan made him stop, simply because HE wanted the credit (and pay) for it.

ME: I haven’t seen examples of that. But even if he had, after Stan made him stop, then he’s not writing dialogue any more, and what Stan wrote was writing, not editing.

What I think you may be thinking of is that Jack would write border notes, to explain what was going on in the panel. But those aren’t real dialogue, they’re sketchy notes. Sometimes Stan would write something similar, sometimes something different, and sometimes he’d completely dispense with Jack’s notes and use the panel to establish something else.

CHUCK: Again, anything that Stan changed was done for what was, in HIS opinion, the better and more simplified version of the story to reach a larger audience.

ME: Stan would write what he thought worked best, yes. It was usually more complex than Kirby’s rough notes, not simpler.

CHUCK: I don’t know many great artists who would see that as COLLABORATIVE.

ME: Whether they would or not, it’s still collaborative, just as moviemaking is a collaborative art even if the director has final cut and can overrule the screenwriter, actors, etc.

CHUCK: But the artist in that situation is starting the process WITH a real plot. The collaboration is true from the beginning. I don’t think it was always that way with Kirby, Ditko, and, from what Romita has said, even himself.

ME: All three of them were plotting and drawing comics with the knowledge and intent that Stan was going to write captions, dialogue and more. That’s collaborative. It wasn’t a collaboration they always liked, but it’s still a collaboration.

CHUCK: Kirby’s Silver Surfer was a STORY in FF #48, and Stan knew nothing about it. That wasn’t a PLOT. It was a STORY.

ME: It was a plot, as we use the term in comics.

CHUCK: Regardless of if Stan used certain words or not, the STORY was already there.

ME: There was a plot there. If it had been published without words, readers would have been very confused. It wouldn’t have made sense as a finished story without the words.

I think what’s going on here is that what you see as “story,” I see as “plot,” but we’re talking about the same thing. When I write a plot for a comic, there’s story structure and character and theme and notes about what they’ll be saying and all the stuff you call “story” when John did it in SPIDER-MAN. But in comics, that’s what we call “plot.”

CHUCK: No no, that’s wasn’t what I meant… the Editor changing words would never even be seen as ‘dialogue’. He was simply doing what an editor does and shoring up the work.

ME: Then that’s not what we’re talking about. If the artist writes a lettering script as well as the plot and art, and the editor edits that script before it goes to the letterer, that’s editing. But that’s not what happened on the Romita-Lee SPIDER-MAN.

CHUCK: Stan CREATED the concept of the Editor making the artist NOT write the words, so that HE could.

ME: He didn’t, actually, though he made it famous. And “making the artist not write the words” is an inaccurate description of it. When Don Heck drew an Iron Man story, or Romita a Spider-Man of Colan a Daredevil, they weren’t itching to write the words if not for Stan stopping them. They didn’t expect to write the words. They’d have been happier if Stan actually wrote a plot.

That they weren’t credited with plotting was an injustice. But they weren’t frustrated scriptures being held back by Stan. Kirby would have liked to script the comics he drew, if he had the chance (or rewritten them from someone else’s script, as he often did in the 40s and 50s), but that wasn’t what he was hired to do. Ditko, over time, decided he wanted to write dialogue. But Romita never did. Nor did Colan or Heck. John Buscema tried it a couple of times, I think, and gave up.

CHUCK: He could’ve let Kirby do his own dialogue, still made his subtle changes (and there are some examples of him doing this from Kirby’s margin notes) and simply been the Editor.

ME: He could have, yes. But he didn’t, so he wasn’t simply the editor. And most of his scripting wasn’t “subtle changes,” either.

CHUCK: He CHOSE to do that dialogue for very specific reasons. Credit and Pay.

ME: He also thought, right or wrong, that his dialogue was better than what they’d do.

CHUCK: I’m sure over the years Julius Schwartz got plenty of stories that were… not done as well as they should’ve been and had to put some time in to clean up the dialogue and sort things out. He never considered himself the writer or co-plotter because of it.

ME: True. And I’d argue that what Julie did on the plotting front was even more than what Stan did, and is illustrative of the problem: The artists should have been credited with plotting.

But what Stan did as scripter was far more than what Julie did as editor of a script, and isn’t the same thing. What Stan did is like what Fleisher did on SHADE, what Levitz did on that LEGION issue and what deMatteis did on the JL books. I’ve dialogued stories from someone else’s plot, too. I got credited as scripter, not editor, because I wrote the words — the captions, dialogue, SFX, etc. I didn’t edit someone else’s words, which is what lie would have done.

CHUCK: I wouldn’t emphasis SOLE writer for the artist… but I think he IS the writer.

ME: You don’t see the contradiction in that sentence? Saying someone is the writer, rather than a writer, is saying they’re the sole writer

CHUCK: Anything added from the dialogue that’s a change, would be Editing.

ME: It’s not. I’ve dialogued too many comics for dialogue to be dismissed as editing.

CHUCK: Really it should read John Romita: Story and Art, Stan Lee: Dialogue and Editing.

ME: That would work for me, too. But that doesn’t credit John as “the” writer, since “story” and “dialogue” are both part of writing.

CHUCK: I appreciate the conversation, but I don’t think we’re going to sway each other’s thoughts on it any…! But hey, it’s fun to discuss…

ME: I hope you’ll entertain the idea, at least, that I’ve got 42 years of experience as a professional comics writer (and even occasional editor) and know what constitutes plotting, scripting and editing. So when I tell you that writing dialogue is not editing, I’m speaking from a firm knowledge of how things work.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m always impressed by how smartly articulate Kurt’s responses on Tom’s form are. There are several other writers I’ve read interviews with whose answers weren’t as sharp. And I don’t think you can gauge just how intelligent & well spoken a comedian c book writer is only by their published comic book writing. I’ll even say Kurt’s answers are slightly intimidating to me. because I’m well aware I can’t reason or communicate on that level. Nevertheless , it doesn’t shut me up. Sorry. 😅

I know the differences between writing, scripting, dialog, etc. is more than just semantics. Depends on the situation, the people I volved, & what they actually did. I’m glad the example of Keith & JM on “JL(I)”.

Comics are different than theater plays, screen plays for TV& cinema. “Script” means “full script”. Events & dialog. So it can be confusing for comics, to credit the person only writing dialog as writing the script. Dialog can contribute to plot. Bendis did it. Claremont, too, sometimes to excess.

I often get different definitions from as many professional artists I ask, on the differences between breakdowns & layouts. They aren’t interchangeable. But not all artists agree which are looser, or which includes more detail than the other.

Personally , if some one just writes dialog, if plot elements are introduced not envisioned in the original plot, not every writer will want the same credit name. ”Dialog” omits the plot points added. “Script” might discredit the visual storyteller who had the original idea, and laid out the story without input from anyone else (if that’s to even allowed by an editor today, depending on the clout of the artist).

Who knows how many plot points JM added in his dialog on JLI? So script might be the best credit.

If it’s an indie, creator-owned project, there’s more freedom to call it what they want. I think Byrne was credited for script on Mignola’s initial Hellboy story, “Seed of Destruction”. In interviews, Byrne said he “just did the dialog”, & that he thought Mike could’ve done just as well. The book was great, either way, & subsequent stories continued to be great after Mike wrote it all himself.

In the few self-published comics I’ve written, I will, like Kurt said, make adjustments and references in the dialogue, based on something the artist added that wasn’t in the initial full script. A character being chased was drawn carrying a duffle bag, which wasn’t mentioned in the script. But it didn’t alter the overall plot, & added a new beat. I made a quick reference to it in the final dialog, by having the guy doing the chasing tell a third character that they could keep the bag. And later the 3rd character mentioned giving the bag as evidence to another, off-panel character.

Anyway, I think it’s hard to quantify what people contributed to a story in succinct, uniformed, across-the-board credits. Esoecially when “script” the as different connotations in other media. But there are differences between “Dialog” and “Script”.

LikeLike

“Comics are different than theater plays, screen plays for TV& cinema. ‘Script’ means ‘full script’. Events & dialog.”

In TV or movie writing, “story” means an outline, and “written by” means writing a teleplay or screenplay. That can be confusing in its own way, since someone can be credited as “writer” who’s working from someone else’s outline.

“So it can be confusing for comics, to credit the person only writing dialog as writing the script. Dialog can contribute to plot.”

Also, what the scripter writes isn’t just dialogue. Captions aren’t dialogue. Sound effects aren’t dialogue. Thought balloons (if there are any) aren’t dialogue.

So calling the person who writes all that the “scripter” is confusing, but saying they only wrote “dialogue” is also confusing. There isn’t a good word that’s descriptive and accurate.

In any case, we call the non-textual stuff a plot, even if the film/TV industry would call it a story or a treatment. And we call the textual stuff either script or dialogue, despite the fact that “script” can mean something else, and “dialogue” doesn’t include everything the scripter/dialoguer writes.

Those are the industry terms, that’s all. Better to use them than try to change them, because they’re not going to get changed.

“I think Byrne was credited for script on Mignola’s initial Hellboy story, ‘Seed of Destruction’. In interviews, Byrne said he ‘just did the dialog’, & that he thought Mike could’ve done just as well.”

John was credited with “Script.” Mike was credited with “Plot & Art.”

Chuck might prefer to credit Mike with “Story & Art,” but it’s the same thing. “Plot” is simply what we call it in comics.

And when John says he just wrote the dialogue, he’s not saying he didn’t write the captions and sound effects. He’s just using a term that is understood to mean “the lettered text.”

And yeah, Mike could have done it himself, but didn’t have the confidence to. Once that first arc was done, he realized that yes, he could do it himself, and did, very well.

“But there are differences between ‘Dialog’ and ‘Script’.”

In a comic book, if there’s a “script” credit and no plot credit, it means that person wrote the whole thing (even if, like Stan, they didn’t).

If there’s a “script” credit and a “plot” credit, then the person credited with script wrote the lettered text.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And to add to that, I’m not sure “script” means anything formal in TV and film.

What we might call a script is formally called a screenplay or teleplay. It’s formally credited as “Written by.”

“Story,” on the other hand, means an outline or treatment in film/TV, but in prose it means the whole job.

“Repent, Harlequin, Said the Ticktock Man” is a story by Harlan Ellison. That means he wrote the whole thing. But if he was credited with “story” in a TV show, he’d only have written the outline, not the full teleplay.

Words mean different things in different contexts, and all industries have their own jargon that doesn’t always mean the same thing in another industry.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“The lettered text.” That’s IT! Makes sense! Includes narration, dialog, etc. That could be the correct credit! But, no one will confuse that with “Lettering”, right? LOL Just kidding.

Thanks Kurt. Insightful as always. Appreciate the distinctions. Story, Script, Outline, Treatment, etc. I have noticed some of the different credits you mentioned in the TV & movies, how multiple writers on the same project can be credited differently. Thanks for including so much in your answer.

LikeLike

>>>Steve McBeezlebub

If you can’t accept that writing involves words and plotting and drawing does not, then yes, there will be no convincing you.<<<<

No one said that or inferred it.

Reading comprehension is important.

LikeLike

I have this reprint too and enjoyed both the art and story. I think I liked that he wasn’t a traditional looking ( The Lon Chaney looking werewolves. Howling style werewolves would show up in movies years later ) and as I would find out later traditional werewolf either.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Correction, Lon Chaney, Jr. looking werewolf.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nostalgic and insightful look mto Marvel’s past and it’s continued Influence on a current Marvel master!

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a kid I got very annoyed in this era — jeez, is he still moping about Gwen six months later? In hindsight, I was extremely clueless about grief.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Not to mention in Marvel Time it was ’bout 2-3 weeks at most.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Right there on the splash page it says “almost ten days”. So not even two weeks.

LikeLike

I read this when it came out.

There was something about Man-Wolf that I did not like, He looked too much like a dog. I think Kane was trying for something between the Werewolf Bernie Wrightson did in Swamp Thing # 4 a few months before this was published and the Oliver Reed Werewolf from the Hammer Film.

I also did not really like how Kane and Romita’s styles converged. I also thought Ross Andru (on Marvel Team-Up tried to get Spider_Man’smask on model (Looking at reprints, Romita struggled with this is 1966-’67.)

I thought Conway was a good (and sometimes excellant) writer, but I thought he struggled with Spider-Man, the FF and Thor in 1972-’75. He both wanted to be different and original . . . and to fill Stan’s shoes. Not an esy task and he might have done it best when he did more original things,(The Thor story where. Thor fights a Lovecraftian being (Where Darkness Dwells, There Dwell I) or the Spider-Man where Spider-Man fought a random mutant while on a trip. (The Mindworm).

Finally, it is odd to me how many times Ditko and Kane swapped characters: Ditko followed Kane on Noman and Kane followed Ditko on Hawk & Dove, Blue Bettle and Spider-Man.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I also like Romita, Sr.’s inks over Gil Kane’s drawing. Gives it a sturdy, well lit finish. Dynamic, overall.

I’m no wolf expert, but I’m surprised Johnny’s close proximity to Peter didn’t allow him to heard growling or snarling. I might be spitting wolf whiskers.

I’m not a fan of Conway’s writing, but this issue zipped along well enough. It’s still high level Spidey era. Feels genuine to the established pathos & ethos.

JJJ sure was a prick, though.

LikeLike

I´ve read this story in he eighties, after skipping the previous issue of the brazilian edition of Spider-Man. And that´s how I´ve learned about Gwen´s death… It would take me a couple of years to complete the collection and read the classic ASM #121 http://www.guiadosquadrinhos.com/edicao/ShowImage.aspx?id=55&path=rge/h/ha00301019.jpg&w=400&h=606

LikeLiked by 1 person

If Peter Parker spent 6 month acting like this in ASM within the last 15 years people on Reddit would be upset about him acting out of character

LikeLiked by 1 person

From the Comic Book Artist Interview with Romita:

John: The only thing he used to do from 1966-72 was come in and leave a note on my drawing table saying “Next month, the Rhino.” That’s all; he wouldn’t tell me anything; how to handle it. Then he would say “The Kingpin.” I would then take it upon myself to put some kind of distinctive look to the guy. “

“We would have a verbal plot together. First it was two or three hours, then it was an hour. Stan would tell me who he would like to be the villain, and personal life “threads” he would like carried on. Generally we would select the setting; sometimes we wouldn’t even have time to select the settings, like “it takes place on a subway.” He would give me that, and tell me where he wanted it to end. I would have to fill in all the blanks.”

In the first response I think he’s talking about having to come up with the character design from Stan giving him a written note with just a name. He was asked if he co-plotted and why some of the characters had a strong Romita stamp.

He goes on to say that he and Stan would plot the book together and he (JR) would fill in the blanks. He was obviously doing a lot of heavy creative lifting vis a vis story, plot, and character design but based on his words here I think it’s inaccurate to say he was writing Spider-man and Stan was just the dialogue guy if they were in fact having 1-3 hour sessions talking about plots.

The entire interview is here: https://twomorrows.com/comicbookartist/articles/06romita.html#:~:text=John%3A%20The%20only%20thing%20he,distinctive%20look%20to%20the%20guy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In cases where they would have a conversation like that, I would say that John deserved co-plot credit (and payment).

I think that in other cases (notably the Stone Tablet Saga and the later story with all the TERRY AND THE PIRATES callbacks), John was working from much less and was doing most or all of the plotting himself.

I’ll also note that the kind of description John gives of a plotting session is the way Julie Schwartz often worked, as well. But Julie called that editing. Guiding the writer, figuring out what story the writer would go home and write.

Stan chose to take full plotting credit when editors who did that at other publishers just got credit (and pay) as editors.

LikeLike

Thanks for the clarification.

I presume that in today’s comic book offices that a greater care is given to making sure credits better reflect who did what and perhaps that’s more or less a standard between the big two.

No disagreement with what you said. My main contention was that based on Romita’s full comments Stan was apparently contributing more to the story process than just giving Romita a note with a name on it and letting him go.

LikeLiked by 1 person