I mentioned meeting my buddy David Steckel in gifted class a couple weeks ago. David was, like myself, an avid comic book reader. But he only liked Marvel comic, and turned up his nose at anything from DC or other companies, which he felt were too childish and stupid. Accordingly, every once in a while he’d wind up with a DC book–he had a cousin who would give him books from the cousin’s collection from time to time–in which he had no interest. And so he started passing those comics along to me. There wasn’t any trading involved, he simply gave them to me as he didn’t want them. And that’s how I came to possess this issue of DC SPECIAL featuring Plastic Man.

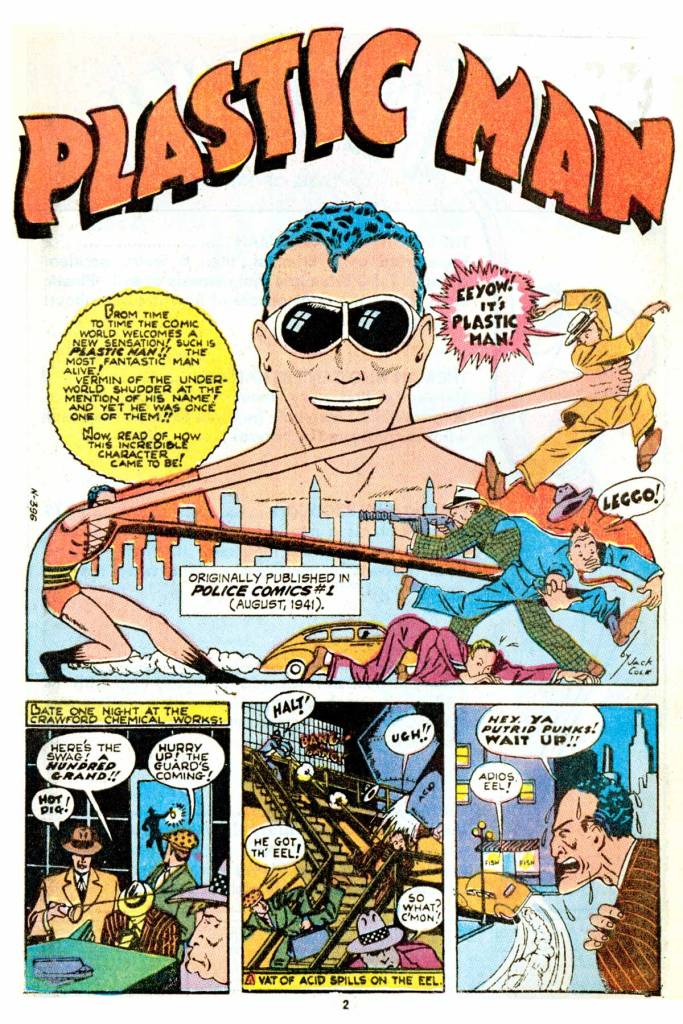

Plastic Man hadn’t started out as a DC character at all. Rather, he was something of a surprise hit for Quality Comics in the early 1940s. He started out as a 6-page back-up feature but generated enough interest that he soon earned the front spot in his anthology home, POLICE COMICS. Plastic Man’s self-titled series ran until 1956, longer than most other super hero series of the era (though the final batch of issues were all reprints.) When Quality Comics got out of the comic book business, they sold their assorted titles and properties to DC/National Comics. This included BLACKHAWK, G.I. COMBAT, and the defunct Plastic Man. DC didn’t do anything with the character for years, until an advertiser made unauthorized use of the hero in a print ad shilling for undergarments, the ad agency apparently mistakenly thinking that he’d fallen into the public domain. DC rushed an appearance of the hero into the most readily available title: the Dial “H” For Hero strip in HOUSE OF MYSTERY. And they also chose to take advantage of whatever public spotlight was now on Plastic Man to attempt a new series with the pliable policeman.

The 1960s revival, though, contained little of the appeal of the original strip. Its humor was labored, it couldn’t quite decide how comedic and how dramatic it wanted to be, and it jettisoned everything apart from Plastic Man himself, surrounding him with a new cast and a new status quo. Eventually in the series, it was revealed that the guy we were reading about wasn’t the original Plas at all, but his son. Papa Plas and Woozy Winks come out of retirement for one last caper. But the book wasn’t successful and the series was cancelled, another casualty of the bubble bursting on the super hero book of the era. Why DC decided to devote this issue of DC SPECIAL to Plastic Man is a bit of a mystery to me–there’d be a revival of the strip a few years later, possibly prompted by good sales of this issue. And there was a constant low level of interest in an animated series, which eventually turned up later in the 1970s as well. But regardless, this issue was chock-full of stories by Plastic Man’s originator, Jack Cole. And they’re all really good.

The issue opened with the very first Plastic Man story, a tale that I had previously read in the later-issued hardcover collection SECRET ORIGINS OF THE SUPER DC HEROES. But after that came a fun yarn that introduced Plas’ sidekick, Woozy Winks. In this initial tale, and for a short time thereafter, perennial grifter Woozy was protected by a charm put upon him by an old man that he helped. With it in force, nothing could harm Woozy, Mother Nature would come to his defense. Woozy initially uses these abilities to further his criminal ambitions, but he isn’t really a bad guy at heart, and Plastic Man convinces him to change sides. Clearly, Cole liked this new character and wanted to keep him around. After a couple of stories, Mother Nature’s protection wasn’t ever mentioned again–presumably, the charm wore off or expired–and Woozy became just another hapless comedic sidekick.

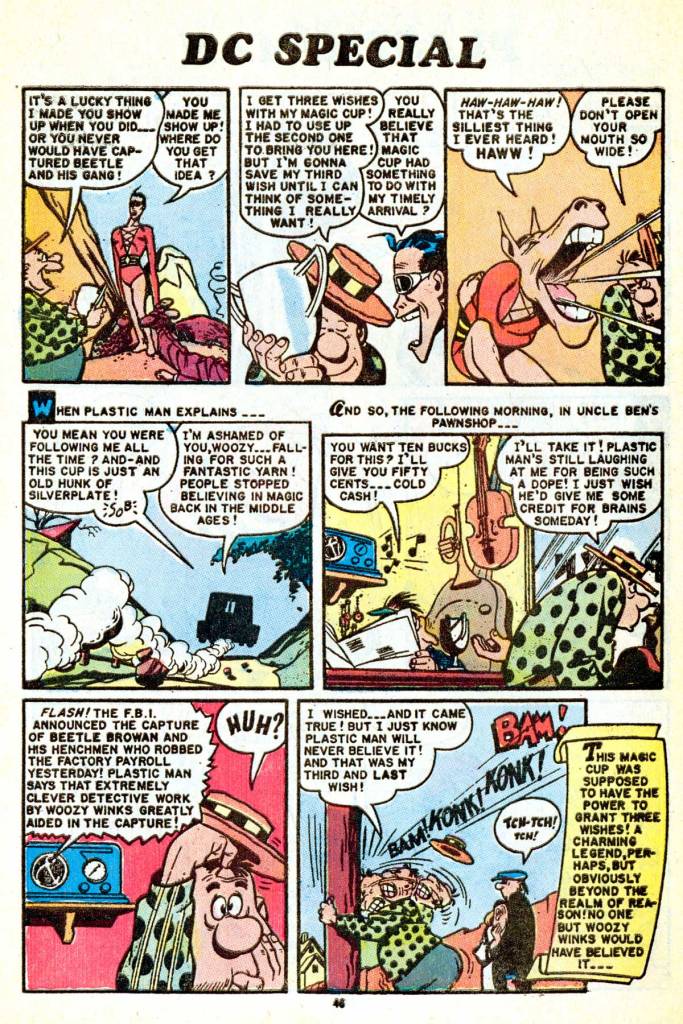

Woozy became popular enough on his own that he was given his own strip within the larger PLASTIC MAN title, an example of which is included in this issue. This story was written by Joe Millard though still illustrated by Cole. And it’s fun, but not as fun as any of the legitimate Plastic Man stories in the issue. This came out during a period where public tastes were turning away from super heroes and more towards comedy features, so it was more in line with that approach. And Cole’s cartooning is always wonderful. I just never entirely warmed to Woozy as a solo player, he needed Plastic Man around to make his antics a bit more palatable to me.

The final story in this issue, written by Bill Woolfolk, is a good example of their dynamic in action. In it, Woozy saves the life of an escapee from an asylum, who rewards him with a silver cup said to grant three wishes. Woozy of course doesn’t believe in such superstitious nonsense–or does he? Either way, Plastic Man doesn’t. And yet, as the story plays out, at three points Woozy makes ad hoc wishes and they wind up coming true, though whether this is the influence of the Cup or just the way things play out is left up to the reader to determine. In the end, Woozy is crushed because he realizes that the magic of the Cup may have been real after all, and he squandered it like a fool . Of course, that squandering saved his life once, so it wasn’t all to the bad. But there you go.

One of the problems most of the Plastic man revivals have had over the years is in not understanding the original strip. They constantly try to make Plastic Man himself funny, a Spider-Man like wisecracker or a drug-addled crazy person. But Cole’s original works the other way around. While on occasion the situations that Plas finds himself in are outlandish, and while Cole cartoons the stories broadly, filling them with sight gags and exaggerated figures, Plastic Man himself is played absolutely straight. He’s a sane man in a cartoon world, despite his ductile abilities. That was on good display all throughout this issue, and as a result, I enjoyed the heck out of it. It made me seek out the other scant Jack Cole Plastic Man stories that DC had reprinted over the years at that point. It was a classic strip, one whose prominence in comic book history has somewhat been forgotten as the character has drifted away from prominence.

That Leroy lettering is jarring and I think it takes away from the story. I have the same issue with EC – it might have been cheaper or faster, but it’s cold.

LikeLike

I don’t know that I’d agree with the idea that the classic Plas was played “absolutely straight.” He was certainly straighter than the manic Plas of the present day, but he wasn’t exactly Reed Richards.

He had a sense of whimsy, turning himself into goofy objects in the pursuit of his foes — and even in the pages you show here, turning his head into a big donkey head to laugh at Wimpy is a gag that he’s indulging in.

He’s not Jerry Lewis and he’s not Spider-Man, but he’s got a sense of the absurd.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with Tom. Surrounded by Woozy and his oddball rogue’s gallery, Plas, even with a sense of the absurd, is the most normal person in a lot of the stories.

LikeLike

“The most normal person in the series” and “absolutely straight” aren’t the same thing, though.

I’d agree with the first description, but not the second.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Plas is a “straight man” in a comedy duo, but he isn’t stiff or reserved. Rather, he’s very expressive. It’s a combination that’s uncommon, but not unknown. Think of, say, a stereotypical Italian man, who is always waving and gesticulating when he talks – but what he says is smart and level-headed. The distinction shows in the panel where he says to Woozy “That’s the silliest thing I ever heard!” and uses his powers to morph into a donkey head. What he’s conveying is a rational, scientific idea. But he’s doing it in with more than words, with a forceful facial expression. It’s basically an elaborate version of a theatrical eye-roll. I think that’s what been lost in subsequent versions. Here, he’s not a wacky character mentally. He’s a fundamentally down-to-earth person who often readily shows his thoughts or emotions, in a way which might seem “wacky”, but is more just very visible on his body.

LikeLike

This was a wonderful issue. There were also a couple of stories reprinted in Jimmy Olsen.

Plas’s continuity got remarkably tangled before Crisis came along: https://atomicjunkshop.com/it-is-easier-for-a-camel-to-pass-through-the-eye-of-a-needle-than-to-untangle-the-continuity-of-plastic-man/#comment-16272

LikeLike

I don’t remember how I acquired this issue, years after it had originally come out. But like Tom, I was instantly hooked by Jack Cole’s amazing, frenetic, surreal cartooning. It’s wild to me that this is the same artist who did those lurid pre-Code crime stories, AND the flat, graphic style of the “Betsy and Me” comic strip, AND those lush, sexy pin-ups for Playboy. What an amazing artist. And what a tragic end for one of the all-time greats.

LikeLike

Hi Tom,

I’ve been reading your blog for a long time and wanted to ask this for a long time. When you mention something like “He started out as a 6-page back-up feature but generated enough interest….” what does that actually mean? How was interest measured back then? How did they know that it was the Plastic Man, Superman, Spider-Man feature in an anthology that generated interest?

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a very good question, and one that I’ve wondered about as well. And I expect that it was some combination of feedback from their distributors concerning retail comments–what the customers were talking about that they saw or heard–and whatever direct feedback there may have been in the form of letters and the like. Letters pages weren’t really a thing then, so almost any quantity of mail about a feature would be a strong indicator that it was something the buying public was paying attention to.

LikeLike

I first was aware of the character through the first DC revival attempt, which, as you say, wasn’t that successful on very many levels. They lumped him in with all the Arnold Drake-style humor characters a la Jerry Lewis and Bob Hope; Angel and the Ape was another of these. I think Gil Kane drew at least the first couple but he was replaced early on by Win Mortimer (and eventually Jack Sparling of all people), who was no hack but he was no Bob Oksner. Anyway, that kind of humor had already become old hat by this time. I first discovered the “real” Plastic Man when DC started reprinting the old Jack Cole stuff in some of their 100 Page Super Spectaculars of the early 70s- I knew then what I’d been missing. That stuff was the uncut funk, as George Clinton said. This DC Special came after those, but I snapped this one up anyway- I kinda preferred Cole’s old style to the more refined (but no less manic) style he ended up with, but they were all good as far as I was concerned. Subsequent revival attempts have not been great (though I will make an exception for Joe Kelly’s Plas in JLA)… like with Captain Marvel and many of the Golden Agers, people just don’t think like that anymore and modern takes have very little of what made those old stories special.

You’re all now two cents richer!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I had always heard that Myron Fass’s use of the name “Plastic Man” in one of his CAPTAIN MARVEL titles was the thing that alerted DC’s lawyers to the fact that the company still had rights to Eel O’Brian. The name appears in the first issue, dated April 66, and then the character appears again in #2 about two months later, but with the name judiciously changed to Elasticman. Depending on the timing it could be that Fass and the ad company both randomly tried to rip off the PM name just because both were rooting around, trying to take advantage of the Bat-hype by using theoretically unprotected names for their junk. If Fass was contacted by DC after CM #1, it must not have made much impression, since in CM #3 he cover-featured a villain called “the Bat,” and in the next two months this character too got a sudden, lawsuit-averting name change to “the Ray.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

To lironhalleck’s question, I’ve always assumed that the more enthused readers actually wrote letters to the company in numbers impressive enough that the editors allowed Cole more pages with PM, though it took a little longer for PM to shove Firebrand off the covers.

LikeLiked by 1 person