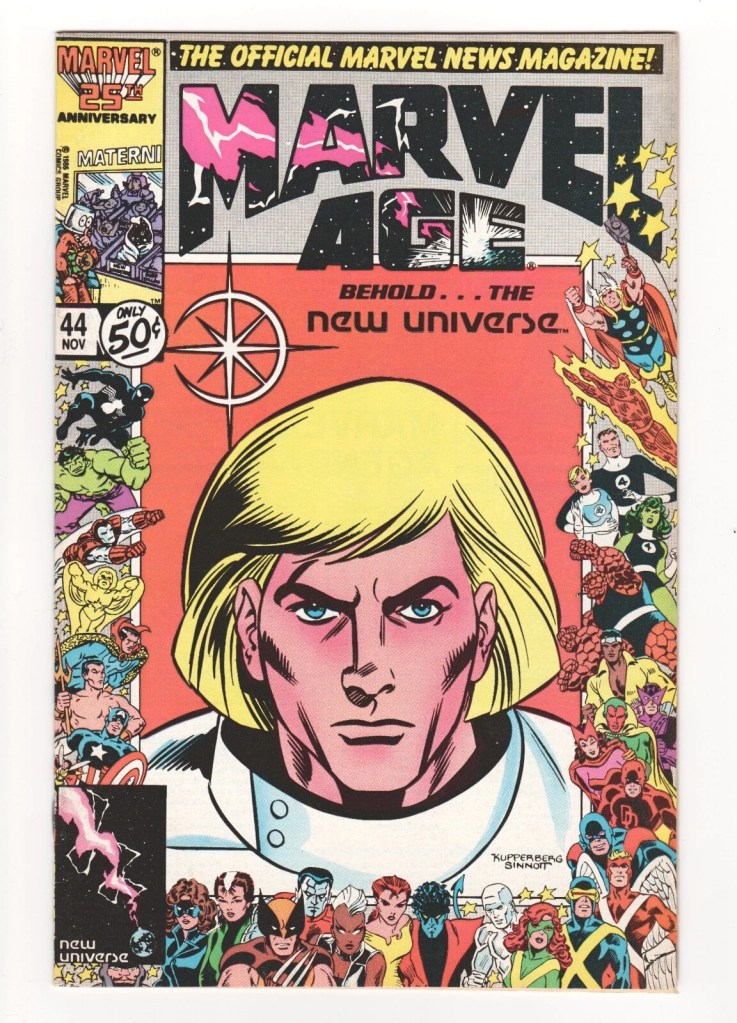

The New Universe was a bit of an epic fiasco in the history of Marvel Comics. it had been conceived as a way to mark the company’s 25th Anniversary as a popular publisher. Instead, it turned out to be an almost-instantly stillborn blemish, a complete creative misfire that was reviled and derided by the fans of that era. And yet, looking back at it, especially in the context of what came thereafter, it’s easy to see the potential that existed there for something pretty novel. There were some good bones in the New Universe, even if they never quite reached the point of being a skeleton that could support a publishing venture. So over the next couple of weeks, we’re going to be taking a look at the eight New Universe launch titles and seeing what can be discerned from them.

The New Universe was the brainchild of Marvel Editor in Chief Jim Shooter. And in fact, in certain circles, it was referred to as the Shooter Universe. Having stepped into the job of spearheading Marvel Comics in the late 1970s, Jim had spent a bunch of years reversing Marvel’s fortunes. He created an editorial structure that allowed for meaningful management of the workload, began to institute stronger emphasis on the fundamentals of storytelling, and expanded Marvel into the direct market in a meaningful way. But having set the ship aright, Jim was increasingly becoming disheartened by aspects of the realm over which he had jurisdiction. There were any number of aspects of the Marvel Universe that he felt were implausible or downright silly. he believed in an ordered universe, and so he strove to get rid of those elements that weren’t to his liking. At his direction, Roger Stern produced stories that eliminated all vampires from the Marvel Universe, for example, and another in which the Savage Land was destroyed. But this was like putting a band-aid on a gut wound. So when conversations rolled around to what the company should do for its impending 25th Anniversary, Jim suggested that they end the current publishing line, bring all of the storylines to a conclusion, and then for the anniversary re-launch the entire Universe again at square one. Only this time, with all of the elements that he didn’t favor left by the wayside. This initiative was internally referred to as the Big Bang. In these days of constant relaunches and continuity reboots and alternate Ultimate and Absolute Universes, the Big Bang doesn’t seem all that provocative. But at the time, it was a radical idea.

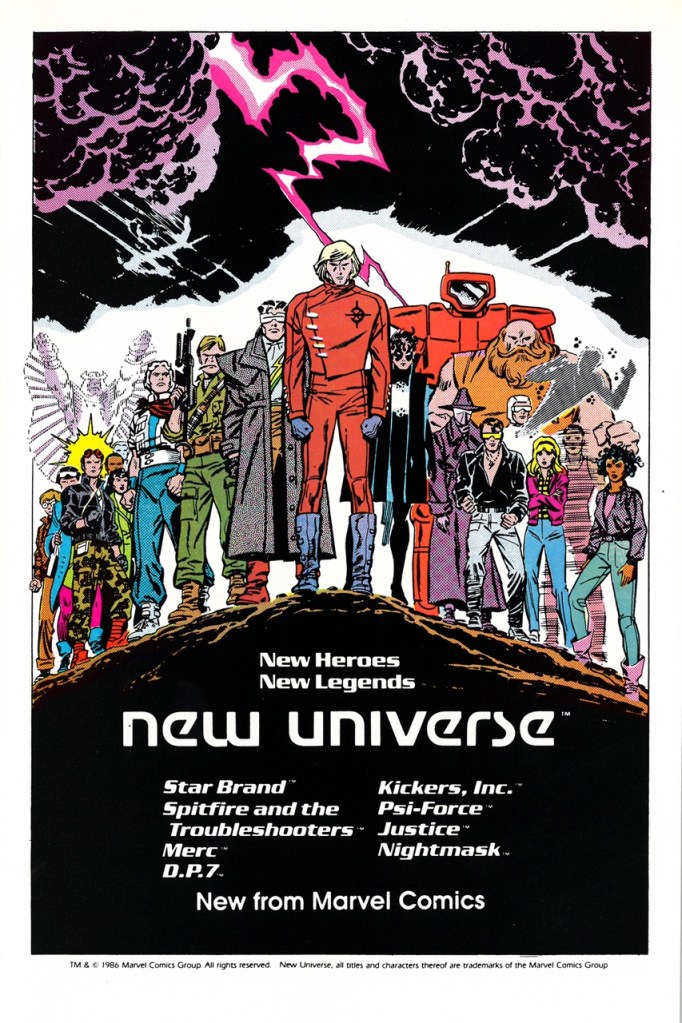

The problem with the Big Bang initiative was that Shooter had done his job too well. The Marvel line was insanely profitable, and the powers-that-be saw nothing but risk in the prospect of shutting it all down and restarting it anew. Additionally, there were several key creators and editors who weren’t keen on this plan, and they took their complaints (overtly or not) to the fan press of the day, who made a meal of Shooter’s plan. So the Big Bang wasn’t going to be a thing, and yet an Anniversary initiative was still called for. Stymied to a certain degree, Shooter suggested that he and his team do the next best thing: produce an entirely new universe of new titles and concepts, one that would be more in keeping with the rigid storytelling logic that he was after. A bunch of rules were outlined for the new effort to guide creators in coming up with properties for it. The New Universe was intended to be “The World Outside Your Window” as the tagline put it, a more realistic venture that was meant to be taking place within the real world. Accordingly, there wouldn’t be any sorcery, no alien life forms, no alternate dimensions, nothing implausible. There would be a single source for all of the change that happened in the world, the “White Event” in which the entire planet was mysteriously enshrouded in bright, white light for a minute, after which beings with superhuman powers would begin to emerge. Even skin-tight super hero costumes were frowned upon; any distinctive garb that the characters would wear had to feel like something that a person in the actual world might be able to put together. The line would also function in real time, just like the lives of its readers, meaning that in practice a month would go by for the characters in-between every issue. And at least at the outset, nobody was allowed to do anything so massive in their storytelling that it would change the state of the world, so any superhuman activity had to stay below-the-radar and not show up on news broadcasts and the like. Most of these guidelines would be bent if not outright broken as the line got started, but in the development stage they felt a bit like a straitjacket to some of the creators who were approached to do work on the new books.

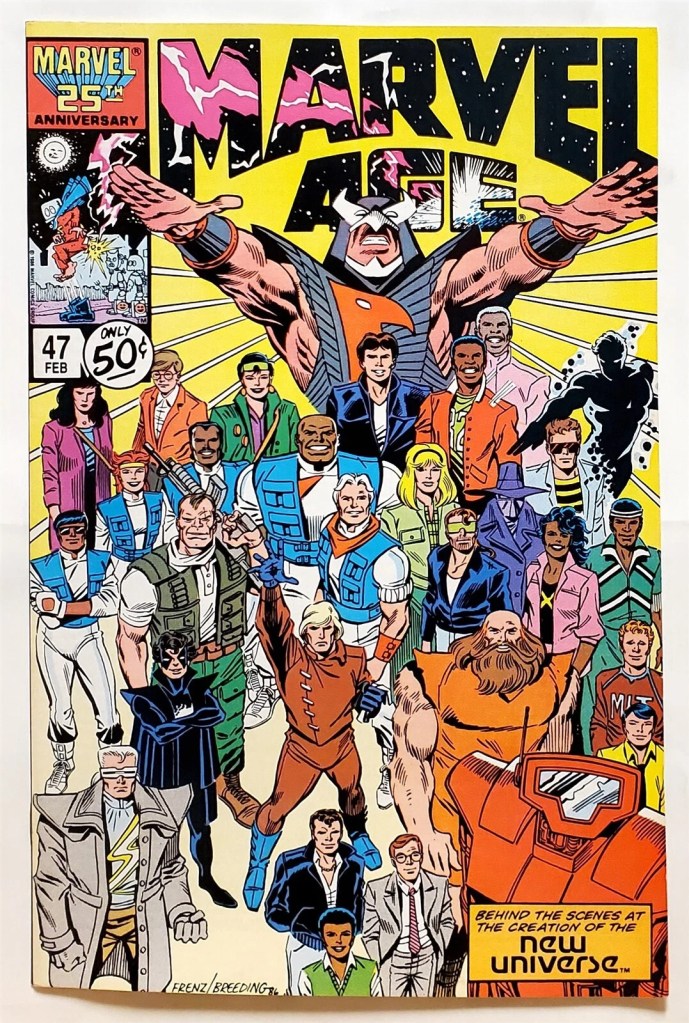

There were other problems as well. for one thing, by the mid-1980s, the battle for creator rights had been going on for a while, and most creators were well aware that anything they created for Marvel under these circumstances would become the property of the company. Most of the more popular creators were unwilling to relinquish their rights to any characters that might prove to be successful. Additionally, the incentive system that Shooter had helped institute meant that those working on popular titles made a ton of extra money in sales incentives. The new titles were untested and untried, so it made more sense for popular creators to remain on X-MEN and AMAZING SPIDER-MAN and the like, where their ancillary income was assured. what this amounted to is that, while the New Universe project was embarked upon with visions of top SF authors coming on board to craft a fully-plausible alternative speculative fiction universe, in practice the New Universe books wound up largely being the creations of editors working on staff (some of whom didn’t even directly write or illustrate the ideas they had come up with.) Creatively, it proved to be difficult to get creators to sign on board, which meant that the launch was fielded by mostly a collection of competent journeymen who weren’t especially popular in the Direct Sales marketplace as well as those who were just starting out and were willing to work on just about anything. The development time had eaten up a ton of lead time as well, for varying reasons, so the books all wound up operating under the gun. Pretty much every title was forced to rely on fill-in creative teams to one degree or another within their initial spate of issues.

Additionally, this was 1986, considered a seminal year in the history of comics, and for good reason. Over at the competition, DC was fielding CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS, SAGA OF THE SWAMP THING by Alan Moore, THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS, WATCHMEN and John Byrne’s MAN OF STEEL Superman relaunch in this selfsame year. And the alternative press was also pushing the boundaries with exciting and more adult-reader-oriented titles such as AMERICAN FLAGG, LOVE AND ROCKETS, GRENDEL, CONCRETE and many others. And MAUS, the first volume collecting Art Spiegelman’s account of his father’s time in a Nazi concentration camp, was helping to redefine just what the medium of comic books was capable of, going on to win the coveted Pulitzer Prize. By comparison, the New Universe titles, steeped very much in Shooter’s approach regarding absolute clarity of storytelling at all times, felt staid and out of step with the industry. Even other Marvel releases of the year, such as Miller and Mazzuchelli’s’ DAREDEVIL: BORN AGAIN or Walt Simonson’s THOR, made the New Universe seem quaint and old-fashioned. Shooter had been trained in making comic books for relatively young readers and it’s an approach that he held to throughout his career, even as the audience for comics grew progressively older and more sophisticated. The New Universe wasn’t targeting older fans, it was attempting to connect with a new generation of young readers. Unfortunately, most of those young readers were more attracted to the tried-and-true Marvel titles that Shooter and his team were putting out, leaving the New Universe out in teh cold.

Ultimately, the New Universe failed to catch on with readers and with retailers, and it began to suffer from weak sales almost instantly. It became a bit of a black eye for the controversial Shooter, who was already under fire in the fan press for other matters. Within a year’s time, Shooter would be relieved of his editorial duties and fired from the company over which he’d presided, and the New Universe would pass into the control of other hands, primarily those of executive editor Mark Gruenwald. Half of the titles were given the axe, while Gruenwald and editors such as Howard Mackie tried to turn around the fortunes of the rest. It was a losing battle, and by the early part of 1990, the New Universe was no more.

The thing is, while he may have become overly didactic about what he wanted and he was never entirely able to get those creators and editors working on the titles to embrace what he was trying to do, the New Universe really does feel like a trial run for the companies and lines that Shooter would create after his time at Marvel. In particular, the Valiant line under Shooter feels like a version of the New Universe done properly–a consistent science-based shared universe in which a variety of characters have grounded, realistic adventures in a story-driven setting that eschews many of the trappings of typical super hero comics. And after his falling out with Valliant’s ownership, Shooter’s later efforts in building the Defiant Universe and the Broadway Comics Universe employ similar approaches. What this says to me is that the New Universe wasn’t intrinsically a bad idea, it simply didn’t come together properly as it might have done under different circumstances. There’s a world where it might have been able to make a go of it and become a success. And there are definitely some interesting ideas buried inside its old, forgotten pages. So while none of these comics is particularly great, they are all pretty interesting–as we’ll see over the course of the next couple of weeks as we essay them.

Ooh, fun! I’ll enjoy reading these! More than I’ve ever enjoyed reading the New Universe comics, probably. I’ve always thought it was a good idea, just done badly…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoyed DP7 and Star Brand but pretty much gave up on them after what felt like a very mean spirited revamp.

LikeLike

Has it been nearly 40 years since the New Universe first launched? One of my roommates and I were avid comic collectors at the time and dove into the New Universe with both feet. However, with the exception of Star Brand for me and DP7 for him, we dropped every title after their debuts. The additional background information helps explain a line of comics that had us wondering what Shooter was thinking. I didn’t last beyond #3 with Star Brand – although I returned when John Byrne had his more vengeful take on the character. I purchased the graphic novels that attempted to bring some life to this struggling line, but was long gone with it ultimately faded from their line,

Given that it has been four decades since the New Universe’s launch, I definitely look forward to Tom’s upcoming reviews.

LikeLiked by 2 people

The basic problem with the New Universe is what I call the “Instaverse syndrome.” Rather than starting with one or two titles, like Shooter did with Valiant, tossing out 8 or 10 new titles all at once. This mistake was endlessly repeated over the course of the 90s. DC also has this problem with their events, where rather than launching one or two new titles, it’s 5 or 6, of which inevitably only one survives, which I call the “Spaghetti syndrome:” Throw it all against the wall and see what sticks. 😉 That being said, I’m pretty sure I bought all the number 1’s, except the Kickers Inc. as the football thing was a nonstarter for me (See also: NFL SuperPro,) but didn’t stick with any of them beyond Starbrand. I did end up picking up Justice after Peter David took it over and revamped what was had been the title that instantly demolished “The “World Outside Your Window” concept. I’m hoping you’ll be talking about the weirdness that happened with the NU in Quasar, not to mention the better stories in Exiles and Avengers.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I liked some of the art by JR,Jr in “Starbrand”. I don’t recall if that was early or later in the series. The character otherwise didn’t interest me. But mid-80’s to mid-90’s JR,Jr is great stuff to me.

I agree with on the Peter David & Lee Weeks issues of Justice. It was dark, but looks really good. The guy was nuts, but the book was interesting thanks to Peter & Lee.

LikeLike

I was a fan of JRJR’s art on pretty everything except X-Men. Something about just makes me itch. Didn’t help that CC’s stories were rather lame, which is odd as CC usually sparks with a good artist, JRJR and Cockrum’s second run being the major exceptions.

Justice was a rare Archie Goodwin flameout. I’m guessing if another writer had suggested it, Shooter would have thrown in the blackball.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, man. From one Tim to another 😉 , I gotta disagree on Jr,Jr’s “Uncanny X-Men”. Sometimes it got sloppy, thanks to the ol’ “deadline style”. And Dan Green used gallons of ink. But there were many, many fantastic panels by that team during that long, X-hilarating run. Certain images, whether covers or interior splash pages, definitive for several of those characters. JR, Jr really made Wolverine “growl” to me. Storm extra noble, in posture & expression. And Colossus, well, colossal. Juggernaut showed up a few times, looking appropriately massive & menacing. Kitty cried, Rogue raged. Nightcrawler pondered poetically. They were the outcasts, the cast-offs. Adamantly bonded together by emotions as well as mutated molecules & over-(re)active atoms. Jim Lee’s broke sales records a few years later, but JR, Jr’s run was “my” X-Men.

LikeLike

I’m pretty much with Tim Pendergast on this (and would have replied to his post if there was a reply option). I think JRJr is really, really well suited to a solo book with lots of action, and far less suited to a team book with lots of interpersonal dialogue.

He got much better at it as he went along — he got much better at just about everything — but in X-MEN he was still figuring it out. There were a lot of nice action moments overall, but so much of the book was multiple-character scenes about standing around (or sitting around) talking and thinking, and that stuff, he did on a much more functional basis than the high-energy action stuff.

Cockrum, Byrne, Paul Smith, Barry Windsor-Smith, Alan Davis, Rick Leonardi, Mark Silvestri, Jim Lee, Whilce Portacio…they were all much more facile with the soap opera scenes, even if some of them would have much rather been drawing Big Action.

JRJr got a lot better at it in time, though I think he’s still best off with solo books, and I think he’d agree. But back then, X-MEN was throwing a lot of stuff at him that just wasn’t in his wheelhouse.

LikeLiked by 1 person

John was still pretty new to the business then, remember. He’d only done his first series with MARVEL SUPERHEROES AT THE SUMMER OLYMPICS (eventually CONTEST OF CHAMPIONS) a little before, & running all those characters at once played at least a little into his getting X-MEN.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, he’d had runs on IRON MAN and SPIDER-MAN by then, too, but they certainly didn’t have the character density of CONTEST OF CHAMPIONS.

But I’m not ragging on him. I think he’s an excellent comics artist and developed into an astonishingly good storyteller. I just don’t think he was, at that time, terribly experienced at the kind of story that had been X-MEN’s bread and butter.

He got a lot better at it.

LikeLike

Kurt, I respect you. We just disagree. I love Rick Leonardi’s stuff, and he also got exponentially better after his 80’s X-Men issues. “Spider-Man 2099”, & inked by the unsurpassed master, Al Williamson, no contest. Legendary run.

Silvestri might edge out JR, Jr on UXM here and there. JR,Jr’s run for me benefitted from my fave roster for that team. I wasn’t as jazzed by Havok or Longshot. Kitty & Nighcrawler (I didn’t want to say “Kurt” 😉 ) went off to Excalibur. But JR,Jr’s also just looked more mythic to me. I can’t imagine anyone else drawing that kooky Kulan Gath 2-pater, “And Age Undreamed Of” (Conan reference) & “Raiders of the Lost Temple” And then the trial og Magneto in Paris.

Alan Davis’s elegance is on another level. But his fill-ins on UXM, as breath takingly glamorous as they were to behold, lacked that grimy underbelly of humanity I had started to associate with the X-Men as drawn by JR, Jr.

As for Paul Smith’s pretty pictures, in my limited opinion there was no better drawn (OK, post Neal Adams) issue of UXM than Mr. Smith’s UXM # 172. It has a sleek Patrick Negal design sophistication feel to it. The deadlines really impacted Paul’s UXM run. Several issues were good, but you could see it where the art rushed. Then Walt Simonson drew # 171, I think, and Paul had more time to invest in # 172, and it shows. Bob Wicek’s inks certainly helped. But Paul reached pretty much perfection. It just wasn’t consistent, and he exited the X-train.

None of the other artists you mentioned satisfied my perceptions of the X-Men as much as JR,Jr did for me. I’m OK being in the minority on this. It doesn’t change the enjoyment I got out of those issues. 😉 I agree His art had the opportunity to be more finely tuned drawing just DD, & later Iron-Man (expertly inked by Wiacek). His DD run was also enormously aided by the sublime inking of the great Al Williamson.

Jim Lee’s was almost too prefect. I liked some of it, especially his Cap popping up in Madripoor. But I like a few flaws in my superheroes, personally, as well as visually. Unless it’s Paul Smith hitting his stride. But his best was still just the essentials, slick but distilled, no details wasted. Sometimes Jim & Williams went too far. Showing off, maybe. 😉

LikeLike

“So while none of these comics is particularly great, they are all pretty interesting” I would consider that a charitable assessment, to put it mildly. With most of the books, blank pages would have been equally interesting.

I think this kind of thoughtful, rational, what’s-plausible approach runs against what most of us read comics for (I will freely admit I have not taken a survey to confirm this). Also Shooter’s approach sounds like a familiar problem: creator feels frustrated working on a book, decides the problem isn’t them, it’s that he has crap to work with. Clearly a massive reboot will fix the problem! It’s akin to a point one of your earlier posts made about editors stuck with books they aren’t sympatico with.

All that said, I look forward to your analysis. For instance I’d vaguely heard Shooter had some kind of Crisis-like reboot in mind but never any details

LikeLike

I’ve often wondered how professionals in the comics industry view AC Comics. Even thought (I think) they’re still publishing, I very rarely have heard of people in comics refer to the company or their titles.

LikeLike

I can’t speak for all professionals, but I think a lot of them view it as a very small-scale publisher devoted to mildly-fetishy stories that are laser-focused on a desire to show lots of cleavage and butt shots. And there’s nothing wrong with that if there’s an audience that’ll support it, which there apparently is.

There’ve been a number of publishers like that, ranging from whichever imprint started LADY DEATH and many who continued it, the Jim Balent company, Zenescope, Heroic and others. And there seems to be a healthy number of them publishing through Kickstarter, as well. Some get more fetishy, some are milder, but the prime attraction is tits, in varying levels of artistic competence.

Bill Black’s been doing it longer than the others, and seems genuinely devoted to maintaining a shared universe of ongoing continuity, largely about hot chicks in costume. A little more story-oriented than most, and with a love for public domain heroines.

I can’t say it interests me a lot, though he’s launched artists over the years who’ve gone on to do more interesting things. But mostly, good for him that he gets to do what he likes and there’s an audience that supports it well enough to continue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve got nothing against AC Comics, but, frankly, I can’t remember a single time any other pro has ever even mentioned them to me. By & large, I’d say they/we DON’T think of AC Comics…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for sharing your thoughts. You’re the first comics industry professional I’ve ever seen comment on AC Comics.

LikeLiked by 2 people

A lot to go through here:

“So when conversations rolled around to what the company should do for its impending 25th Anniversary, Jim suggested that they end the current publishing line, bring all of the storylines to a conclusion, and then for the anniversary re-launch the entire Universe again at square one.”

Shooter always insisted this was a brainstorm that never rose above the level of “chatter.” Marvel’s sales were fine. If it ain’t broke, you don’t fix it. The sales department and the distributors for the newsstand market, which at the time still accounted for the majority of Marvel’s sales, would have vetoed something like this the moment they heard about it.

“there were several key creators and editors who weren’t keen on this plan, and they took their complaints (overtly or not) to the fan press of the day, who made a meal of Shooter’s plan.”

Please name these creators and editors and the publications they went to.

With the latter, I know it wasn’t The Comics Journal or Amazing Heroes. I also cannot imagine any editor doing this, because attacking one’s employer in the press is a guaranteed way to lose one’s job. (Freelance creators at the time were given more latitude.) The only creator I know of who blasted the alleged “Big Bang” plan in the fan press was Doug Moench, and it was many years after Shooter had left Marvel. I should note Moench has a big grudge against Shooter. He also has a penchant for exaggerating and outright making things up with his recollections. Most importantly, he would not have been privy to any discussion of this sort inside Marvel. Shooter blackballed him from working on Marvel’s company-owned titles in 1982. The blow-up which led to that also apparently permanently alienated him from Mark Gruenwald and Ralph Macchio, seeing as how neither ever worked with him again.

“There were other problems as well. for one thing, by the mid-1980s, the battle for creator rights had been going on for a while, and most creators were well aware that anything they created for Marvel under these circumstances would become the property of the company.”

I don’t think this was a concern. Marvel began a character-creation incentive plan in 1982 that gave creators a financial interest in the characters they created going forward. To the best of my knowledge, Marvel creators of the time, such as John Byrne, Chris Claremont, Walt Simonson, and Louise Simonson, are still making money from it. If creators wanted ownership of new ideas, there was the Epic imprint and the graphic-novel line. I’m trying to think of a Marvel creator of the period who left a Marvel-owned title assignment to work on a creator-owned project for an indy publisher. (DC didn’t offer creator ownership at the time.) I’m drawing a blank.

Shooter said the problem the New Universe had with attracting top-tier talent was that the project had its budget substantially cut shortly before launch. They couldn’t afford to pay the higher rates, and had to go with less expensive talent as a result. That seems much more likely.

“Additionally, this was 1986…”

I fully agree the New Universe lacked the freshness of the titles you mention. But it’s probably worth noting Marvel was also doing its part in 1986 with cutting-edge publications such as ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN and THE ‘NAM, both of which outsold everything you mention except DARK KNIGHT and MAN OF STEEL. THE ‘NAM also got heavy mention in the “Comics Aren’t Just for Kids Anymore” newspaper articles of the time. MOONSHADOW wasn’t a big seller, but it rates mention in that company, too.

“It became a bit of a black eye for the controversial Shooter, who was already under fire in the fan press for other matters. Within a year’s time, Shooter would be relieved of his editorial duties and fired from the company”

Contrary to your implication, Shooter was not fired because of his editorial decisions or sales.

The New Universe’s failure notwithstanding, Marvel’s sales during Shooter’s last year there were the best of his tenure, and Marvel’s best year since World War II. Twelve established ongoing titles–I’m not including new-title launches or limited series–averaged unit sales of over 200,000 an issue. Five of those sold over 300,000 an issue, and two of that five did better than 400,000. In 1986, DC had no established ongoing titles that averaged over 200,000 an issue, and neither did anyone else.

Shooter was fired because administrative disagreements with Marvel president James Galton had made their relationship toxic. The last straw was when Shooter sent a letter to New World Entertainment, who had recently purchased Marvel, denouncing Galton and his ethics.

LikeLike

I seem to remember the Journal throwing shade at Shooter for numerous reasons, but doubt that anyone there even paid attention to NEW UNIVERSE.

Anniversary events aside, isn’t there a good chance Shooter was hoping that his universe would be so successful that he would be “too big to fire?” But Shooter had done his job too well, making 616 consistent enough that, as Tom said, young fans wanted to read X-MEN and SPIDER-MAN, not new stuff.

LikeLike

Trust me, when Jim launched the New Universe, he already thought he was too big to fire (no pun intended) & Marvel didn’t so much choose to fire Jim as he thrust it upon them. It was not in the works before it happened.

LikeLike

d9dunn–

I recall R. Fiore, one of TCJ’s most notable contributors, devoting all of one of his “Funnybook Roulette” columns to the New Universe and reviews of the debut issues. He was very harsh.

As for Shooter not being “too big to fire,” well, if he hadn’t been too big to fire by this time, he never would have been. He had by far the strongest commercial instincts of anyone working in comics editorial at the time. Marvel’s growth and diversification during his tenure was an exceptional achievement, and not just in comics, but by the standard of the publishing world as a whole. Overall, his last year at Marvel could be argued to be his strongest sales-wise, and other new launches, such as Classic X-Men and The ‘Nam, were big hits.

Shooter was fired when his conflicts with Marvel president James Galton boiled over in early 1987. I’d be very curious to see Galton’s employment contract. He came to Marvel in the mid-1970s after being fired from the presidency of the CBS-owned Popular Library. Any executive that happens to learns to cover their back. Between 1983 and 1986, he was a part-owner of Marvel and could have had the contract written to his specifications. I suspect there were some nasty poison pills if there was any effort to fire or sideline him.

I’m not sure the New Universe, at least during Shooter’s tenure, could be considered a commercial failure except by Marvel’s internal sales standards, and maybe not even then. Marvel’s policy during most of the 1980s was to cancel any newsstand-distributed color series that fell below 125k in unit sales. (There was some flexibility with this, but it was the general rule.) Marvel dropped several titles with sales that every other publisher would have killed for. Star Brand, D. P. 7, Justice, and Psi-Force all apparently sold well enough to keep going after the first year. A new line that bats .500 during its first year isn’t doing too badly.

LikeLike

oh sure, I wasn’t saying that Shooter was fired for the failure of the NU. Earlier conversations here have established how JS butted heads with Galton, and some of JS’s own comments online specified that he accused Galton of stealing from the company, more or less. What JS might not have realized is the contingency you pointed out, that the company as a whole might be OKAY with Galton stealing from them if indeed there was some sort of unbreakable Galton contract. The idea that JS might have wanted to further secure his hold would just be business as usual for any editor– though I don’t disagree with SG’s assertion that JS probably was never “insecure” about his editorial prowess.

I’ll have to hunt around for that Fiore review. Maybe I forgot it because it was just the usual Marvel-bashing of the time (heh). But my main point was that the dominant critical mood at tcj was anti-Shooter whether he was doing regular superheroes, the NU, or EPIC. If some Marvel employee had come to TCJ with some dire story about the NU’s genesis– even if that meant that the employee burned his bridges with Marvel– I feel pretty sure that TCJ would have run such a story. This was the same magazine that deemed it “news” to quote some Marvel memo in which JS called his readers “little effs.” Yeah, TCJ, like hardcore Marvel readers were going to be so offended by that dis that they’d drop all the books they’d been collecting for YEARS. But I don’t remember any NEWS coverage of NU beyond the basic stuff.

JS’s desire to make the Marvelverse more coherent may have been one oriented on editorial preference. An editor’s better off not having to worry (say) about whether Professor X once had a line of mental dialogue about having the hots for Jean Grey– a line that everyone forgot until one writer (guess who) brought it up again. But I’d agree with all here who’ve said that the charm of the MU was that it WAS messy and unpredictable.

The only NU book I liked– and which I occasionally revisit– was Gruenwald’s DP7. I’ll be interested to see if Tom has a take on that one.

LikeLike

Word I had from contacts inside Marvel at the time the New Universe was concocted – I was living in Los Angeles by then & I never had this confirmed by Jim (he & I chatting was a pretty uncommon event even when I was living in Manhattan), so please take it as heresay – was that the NU titles would be so successful – b/c of the Shooter approach that would immediately be recognized by the audience as vastly superior to, as you mention, the sprawling, shambling “storytelling” of the then-existing Marvel Universe – that the sales of the regular Marvel titles would start to fail, & as each “Marvel” title was cancelled, a new New Universe title would take their place, until finally the New Universe had the only titles left & reigned supreme. By which point “Stan Lee Presents” would be replaced on splash pages by “Jim Shooter Presents.”

I’d say the main problems with the New Universe (which you cover pretty well, Tom, so this is an adjunct to your commentary, not a contradiction) were none of the concepts were especially original – to some extent it seemed like readers were being asked to give it a go not b/c the characters caught their imaginations but because the New Universe concept was all the rationale they needed – & very little of the development was especially exciting or eyecatching. There was nothing especially explosive or scene-changing about it, & that’s what it needed. Most other “new universes” pushed by any company since have faced, and fallen on, the same problems. I suspect much of the problem lies in the planning: everyone wants to be “Marvel” out of the gate, & the NU was no different, but Marvel wasn’t really Marvel for a LOT of years after FF#1, & virtually NONE of it was planned. It accrued pretty haphazardly – what, as you mention, Jim was rebelling against – but while I can see something thinking that a weakness of the MU, it was also its great strength. Creating your entire continuity ahead of time – which almost every intended “new universe,” even today, seems prone to (I know both Dark Horse’s “Comics Greatest World/Dark Horse Heroes” & DC’s !mpact Comics were bibled within an inch of their lives) – is a great way to sap huge amounts of energy out of the comics you produce. Near as I can tell, that’s exactly what happened with the NU, give or take a couple titles.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Your first graf sounds like someone mocking Shooter and his attitudes rather than reporting on them. By all accounts, he was quite ambitious and could be a persnickety pain in the ass to work with at times, but that description is really over-the-top. I wouldn’t take it literally.

LikeLike

Given my source, I’m inclined to believe it was a more or less accurate report, but, like I said, please take it as hearsay. I didn’t get the idea he intended it in one fell swoop, but as a very gradual thing. But I don’t recall whether the NU titles had “Stan Lee Presents” on them or not. (I didn’t pay much attention to them.) Anyone?

LikeLike

Replacing “Stan Lee Presents…” with “Jim Shooter Presents…” is beyond “the brave & the bold”. Holy smokes. Kind’a is over the top, as RSM said. Raises the question, if it were true, if there’d be motivation to let some of the old titles tank. But that’s now a moot point.

“Comics’ Greatest World”! Word play on Marvel’s FF being the “World’s Greatest Comic”. I’ve told you before, but I really enjoyed your “X”, with Doug Mahnke, Chris Warner, Javier Saltares, etc. Great design by Warner, too. Then Miller did a pretty cool cover.

LikeLike

Thanks, I appreciate that. Frank did a bunch of good covers for the book, but they came fairly late in the run.

I doubt Jim would’ve gone out of his way to kill off any titles that were successful for Marvel, but there were always marginal or, frankly, dead titles that easily could’ve been pruned, &, as I said, the way I heard it the dream (not so much a plan as a dream) was to slowly fold in the new & let that gain momentum as the old lost it. Way I see it, the “scheme” was predicated on the old school philosophy that the audience for comic books rolled over every four years – Len Wein told me that himself when I started hanging around Marvel in 1978, & he wasn’t the only one who subscribed to it – but if that had ever been true the Direct Market blew it completely out of the water by catering in substantial part to aging fans, so it was perhaps not the best environment for trying it out…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Steven, I apologize if I remember this wrong, but I was initially blown away when I thought I read you quoted somewhere (or maybe in one of our brief exchanges in email or on Twitter or BlueSky) that you wrote X as a villain, not as a hero. I mean, he went up against many characters worse than he was (Ziggaraut, and all those mobsters, crooked gov’t officials, and that exotic guy with the sword who visually struck me as across of Fu Manchu and Ra’s al Ghul). I think Ron Wagner was drawing “X” by then.

But, again, just in my own limited perception, you’ve always kind of pulled from the murkier end of the pool, whether with the Punisher, “The Damned”, or “Badlands”. It gets hazy, dark, but never only black & white (well, “Badlands” was literally published in B&W, but I hope you know what I mean). The characters are shades of gray. I guess the most interesting ones are. Even “Whisper” got morally ambiguous. But compelling.

LikeLike

X as a villain is more or less true. His motivations were certainly more villainous than heroic, tho’ ambiguous or pragmatic are probably closer. He viewed the city of Arcadia as his property, really, and not to put too fine a point on it, he didn’t like other people shitting in his toilet, if you get my drift.

I’ve never been especially fond of “heroes” or the idea of heroism as a steady state, & I loathe the idea that people would call themselves heroes, which strikes me as a whole different level of ego. The fun of writing “not heroes” (not exactly the same as villains or even antiheroes) is they’re capable of a much wider range of response, emotional & otherwise. “Heroes” are kind of strapped in by audience expectations, unless you want to totally decontextualize the word heroes (or, maybe, recontextualize it to its original meaning in the Ancient Greek world, of simply “men of might” with no moral implications whatsoever).

But when I read Amazing Spider-Man as a kid, he was perfectly capable of running away from or ignoring a fight (ft. 17-18) when he had other things on his mind. I always thought that was a perfectly reasonable way to behave, & it struck me as something someone in his situation would do. Years later, I wrote a scene (Marvel Team-Up 94, where I 1st worked with Mike Zeck) where, for reasons, Spider-Man walks away from a fight, & got called into Shooter’s office for it, where he read me the riot act b/c “SPIDER-MAN NEVER WALKS AWAY FROM A FIGHT!” I didn’t argue the point – the issue was already published, so it wasn’t like I had the change anything, but it certainly didn’t put me in solid with the boss – & I left thinking it’s kind of dumb that a fight, esp one that’s not really necessary (as was the case in my issue), must override all other concerns. Part of what led to Whisper. Someone asked me on a panel in San Diego why I took Whisper to First instead of trying to sell the book to Marvel. I skipped the economic reasons & gave the philosophical one: Marvel is a world where massive doses of radiation make you a better person, and that just didn’t jibe with my experience.

Anyway, I don’t expect anyone else to feel this way & I’ve no interest in winning converts, but the concept of “steady state heroism,” where the “hero” refers to themselves AS a “hero” (to mangle Robert Frost, hero should be a gift word; only other people should call you a hero) & is always at the ready to leap headlong into instant heroic action, doesn’t really dredge much interest out of me… (Unless we’re talking, say, Superman, who exists to be heroic – but I still don’t think he’d ever THINK of himself as a hero, but as a guy who’s just doing his best to help where he sees help is needed… It’s not like I don’t understand the concept, I just don’t get much emotional juice from it…)

’86 for the Punisher Mini-Series BTW, though I’d been trying the idea since ’76, & the ’86 version was the ’76 idea w/the prison issue added.

LikeLiked by 2 people

@Steven Grant. Thanks for that. “Steady state heroism” is a new term for me. But I really like the idea of hero as a “gift word”; only others should call someone a hero. I know some brave, selfless people who’d only be embarrassed by or dismiss receiving the compliment. Somebody told me once that “hero” may have come from the Egyptian god “Heru”. And since you mentioned it meant “men of might”, without any specific alignment to good or otherwise, maybe a linguistic link is likely. Heru was described as mighty in his own right. Lots of cross pollination between those cultures over the lost centuries.

“…Superman, who exists to be heroic – but I still don’t think he’d ever THINK of himself as a hero, but as a guy who’s just doing his best to help where he sees help is needed….”

Perfectly said. Have you ever written a Superman story? I’d like to read that. I can’t think of one. That’d be something very different while still maintaining what’s great about the character.

I guess Tom got to edit Superman in Kurt & George’s “JLA/Avengers”. And I read Kurt’s Superman. I like the character, so any time a high caliber pro I’m already a fan of gets a shot, I have to see what they do.

LikeLike

Far as I know, I’m the only one who has ever used the term “steady state heroism,” but it’s sort of a tenet (which is to say lie) of our culture that if someone does something heroic in one circumstance – &, believe me, I totally accept people are capable of acting heroically, & selflessly – it’s their disposition to act heroically under all circumstances, otherwise they’re hypocrites. Or if they commonly behave heroically, they should be given extraordinary benefit of the doubt if behavior to the contrary becomes “known.” All that’s fine if all you’re interested in is the ideal, but people are a lot more complicated than that, and everyone’s life contains a lot more stresses & conflicts than anyone else, certainly any who aren’t intimately familiar with them, knows. That’s why I coined the phrase, but I see little evidence steady state heroism is a real thing, tho’ of course some people come a lot closer to it than others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

BTW, I wrote Superman a couple of times, but really only in cameos: Challengers Of The Unknown 15, which was a pseudo crossover with the Millennium Giants big event that was forced on us to bring attention to the book then, as I expected all along, it was never so much as acknowledged, let alone referenced in any of the Superman books at the core of the event, which would’ve gone a much longer way toward bringing attention to the book.

Then there was the Superman graphic novel, Blood Of My Ancestors, an idea Gil Kane sold them of the first in the line of El on ancient Krypton. It was originally intended as an Elsewhere novel, & Superman wasn’t in it at all, but Gil was only halfway through it when he died & it was shelved for a year or two until John Buscema showed up to finish it. But by the time we got the go-ahead to start, the Elsewheres line had been canned, so it was converted into an in-continuity (sort of) graphic novel with a Superman framing device, so I wrote him on those five or six pages.

I think I did an okay job with him, but I’m probably not the best person to judge…

LikeLiked by 1 person

The point of “heroes” in Greek mythology was mainly that as great as you may think you are – & these are the greatest mortals who ever walked the earth – you’re still less than a bug compared to the gods… though the stories clean up a bit in the retelling as Greek culture ages, like we cleaned up Grimm’s Fairy Tales. Instead of dying ignominiously by wear a shirt poisoned by his wife & his corpse disposed of like everyone else’s, Hercules/Herakles eventually gets retold into getting taken up to Olympus after his death to be with his father Zeus. But great men (heroes) coming to bad ends remains an ongoing theme in Greek myth & legend right down to the end, where the greatest & most noble of warrior – the Trojan Hector, strangely enough – is cut down by Achilles (who’s a bit of an obnoxious bastard from the word go) mainly b/c Achilles is invulnerable so there’s not much Hector can do against him, & then Achilles defiles Hector’s corpse by dragging it all around the battlefield behind his chariot. Then Achilles dies ignobly, by being shot in the hell, his one weak point, by an arrow from Paris, who could be read as the villain of the saga. But “heroes” tend to end up on the wrong side of fate overall, to get the “bug to the gods” idea across.

I’ve never run across any connection between heroes & Heru. I’ve heard it connected to the Greek word “hera,” & some speculate it did reference “protector,” but the only things anyone’s certain of is it goes waaaaaaaaaaay back, & no one’s certain where it came from.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re right. Even those we admire have flaws, dirty underbellies. I guess it’s whether the good they do outweighs the bad. There are exceptions, like people we know who never got famous, but damn, they were always there for us. Selfless, putting others first. Parents who may have been brilliant, but whose circumstances kept them bound to responsibility- so they sacrificed to enable their children to have the opportunities they themselves didn’t have. My grandparents were like that. To see what’s possible, even if it wasn’t for themselves. Moses helps his people to the Promised Land, but can’t enter it himself. As Bono said, “vision over visibility”.

This may sound naive, but I see AOC a bit like this. Selfless- putting the benefit of others before one’s self. I don’t see evidence of a sinister side to her as some of the figures we’ve already recognized as great. I’m not putting her on the level of an FDR or a Ghandi. Those guys did great things. Monumental things, But they had “moral” failures, too. FDR & the internment camps for of Japanese descent, his tolerance of racism against Black Americans, too. Ghandi’s neglect of his children and bias towards Hindus over Muslims (please correct e if I’m wrong on that).

I respect & admire guys like Ralph Nader and Bernie Sanders. The only shortcomings I see from them is cantankerous impatience from those who willfully sow doubt to weaken support for their ideas, & try to get them dismissed for “having to only have it their own way, no willingness to listen to others”, etc. Even if the doubt is legit, I guess Bernie gets tired of repeating himself, or he might think their questions are meant to discredit his ideas, and deflect from real solutions. I shouldn’t be using actual examples, sorry. I should stick to hypotheticals as to not drag this into politics.

Real quick on another point you mentioned that I agree on with you. “Spider-Man never walks away from a fight!”. Well, then he’d never have time for anything else. And he has to make time for Aunt May, Mary Jane. He needs to earn $$ to eat and pay rent. He has to come up for breath, or go nuts.

I’m sorry I forgot about “Blood of My Ancestors”! J. Buscema did precious few DC pages, so I had to get whatever I could find. His drawing “Imagine Stan Lee creating Superman”. His “Batman: Black & White” back-up written by John Arcudi. And your Krypton historical saga. Yeah.

I loved your use of (and the great John Paul Leon’s rendition of) Batman in your “Challengers of the Unknown”. So good. But I missed that Superman appearance. Yeah, those mandated crossovers they force into other series can often be intrusive. I’ll have to look that up. I had forgotten about the “Millennium Giants”. I recall the name after you mentioning it, but I have no recollection about the story behind it.

“A bug compared to gods” is a great perspective. We sometimes cheer for those who attempt greatness, “defy the odds (or gods)”, as long as they don’t cause suffering to others along the way. Or those who risk defying the current limitations or status quo because they want something better for the people they love. That self-sacrifice again. If you risk it all, but only for selfish ends, you’re now almost on the opposite side of the rest of us bugs. 😉 Or look at those of us who haven’t taken the risk, as bugs. Thinking of us as lesser than themselves, so we deserve to be taken advantage of. Maybe that what Lex Luthor thinks. I might be getting distracted…

I wish comics had used the “Herakles” name… I think George Perez did in his “Wonder Woman”.

Just you say that Herakles’s “ascension” to Olympus after his death (“the funeral pyre burned away the mortal parts, leaving only the godly”), was added later, I’ve read that Achilles’ invulnerability was, too, like 300 years later. Roy Thomas coined “retcon”, “retroactive continuity”, but apparently the practice is almost as old as human imagination. Achilles was so swift & strong, & skilled hat he was practically untouchable in battle. But somebody decided to pump up the myth even more. Being held by his heel, dunked into the River Styx. Brilliant and compelling ideas. Not so different than in comics, when “new revelations” are revealed about the characters & stories we “only thought we knew”. If you’re making a living as a storyteller, it’s smart to give people what they might want to hear, especially if it’s something they hadn’t thought of themselves…

Madeline Miller’s 2011 depiction of Achilles was compelling and offered a different take than I was used to, while still paying tribute to the stories I’d heard before. An expansion, but one with the glaring omission of his invulnerability, because she concluded that it wasn’t one of his earliest told attributes. And the ending of the 2004 movie “Troy”, where Achilles’ fellow Achaeans/Greeks find his lifeless body, with just a single arrow, stuck into him above his heel. So the story grows. That was clever.

It was no longer that he was just a much better fighter than everyone. That he was faster, stronger, more skilled. He must’ve been part divine. Wait, he COULDN’T be harmed. You know what, he was INVULNERABLE. Well, then how…? Oh, he was dipped into the River Styx. The river of death. Immunity due to exposure before we knew about immunity. Or maybe some ancient doctors had already considered that idea… And who would’ve had access to Tartarus to dunk baby Achilles into the Styx? His nymph/divine mother, Thetis, of course.

Man, I hope we don’t fall into the abyss, either individually or all of civilization, before I get to watch Christopher Nolan’s take on “The Odessey”. 😉 Wow, that’s petty of me.

LikeLike

Mr. Grant:

Your comment reminds me of Hemingway’s comment that in Spanish (particularly when talking about bull fighters) you would not say, ‘He was brave” but would instead say. ‘He was brave that day.”

Courage and heroism are (to a greater or lesser extent) conditional.

It also implies this question: if someone is doing the the right thing, at potential cost to themselves, are they doing it because it is the right thing or because not doing it is contrary to their own self-image?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Never heard that particular Hemingway quote before, but, yeah. That sums it up. Thanks.

I just realized the idea is also the core of the prose fiction I just turned in for Legends Of Indie Comics Words Only Vol 2.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“I don’t recall whether the NU titles had “Stan Lee Presents” on them or not. (I didn’t pay much attention to them.) Anyone?”

Based on a quick sampling of a handful of them, they didn’t.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Didn’t think so, but it’s been a long time since I’ve put any thought at all into the New Universe.

Your quick sampling reveal any “Jim Shooter Presents…”?

LikeLike

Nary a one.

LikeLike

Didn’t think so, but again, long time…

But this at least establishes that the New Universe was actively eliminating Stan as a legacy feature of Marvel Comics…

LikeLike

For whatever it’s worth, there was no “Stan Lee Presents” on Epic Comics or Star Comics either (again, from a spot check), so it seems likely that at some point before the New Universe, the decision had been made only to use that on the regular Marvel line.

And all of that happened while Stan was at least titularly publisher, and while he might not have noticed for a while if they did it without consulting him, I think it’s likely they would have had him sign off on it.

LikeLike

I remember when these came out. I was getting a little bored with a lot of the Marvel/DC output, so theoretically, a “fresh start” might’ve had some appeal. But as I heard more about them, and flipped through a couple, there was just nothing there to get excited about. I didn’t know about the behind-the-scenes factors that were undermining the line before it ever got off the ground; I just saw it as a massive misfire, and further evidence that Marvel Editorial was out of touch.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Never bought one… though I flipped through them on the stands when they appeared. It’s a puzzler why Shooter or anyone would think that a younger audience would glom onto books with less colorful characters with a more grounded real-world approach? It seems like a possible avenue to get new readers who are older ,and not inclined towards traditional super-heroes… but they probably aren’t searching the spinner rack.

Looking at the crowd of NU characters… they’re a pretty dreary looking lot. All and all it’s a pretty poor idea for a 25th celebration of Marvel Comics. Probably would have been cheaper to repair the rifts with the founding creators and move from there… which is how anniversaries normally work. Easier said than done I suppose.

It’s possibly a pretty good case study of a seasoned and talented pro (Shooter) perhaps not really understanding one of the major appeals of the product….Marvel Comics could be sloppy….and sloppy could lead to surprise and delight.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s a really good observation. I started reading Marvel in the early ’70s. By all accounts, the office back then was in a state of chaos, but the comics that came out of that chaos were wild and exciting! Guys like Gerber, McGregor, Starlin, and Englehart were taking big swings…they didn’t always work, but they were never boring. I’ll take that any day over something that’s technically competent but uninspired.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah. One of the cool things about the Marvel Universe — and DC, too — was that it could have just about anything in it. And if something didn’t work, you didn’t have to drag it out on stage and kill it. You could just ignore it, and then it wouldn’t exist. If it’s not on stage, it’s not a thing.

It was easy enough to ignore the licensed characters Marvel no longer had the right to, and the very same thing could be done with characters Marvel owned but didn’t want to use. It’s not like the SKY-WOLF cast needs to be checked in on every month or anything.

But too many people wanted to “tend the garden” of the Marvel Universe, which meant trimming off the parts they didn’t think were any good. The problem with this is twofold: First, it means bringing stuff you don’t like on stage, wasting pages disposing of it when you could be doing something else. And second, it means you’re getting in the way of potential writers in the future who have good ideas for those concepts.

Which I suppose is the idea, but it’s a bad idea.

I’ve certainly written out any number of characters I had no use for, but generally because they were too tied up with characters I was using to ignore. If I was writing Baron Zemo regularly and didn’t bring up his wife, readers would ask. If I did a big long Kang story without the (ugh) Anachronauts, readers would ask.

So I killed them off — but in one case, I did so off-panel, in an unsubstantiated report, and in the other, I did it in Limbo, where time doesn’t work normally. So it’d be a snap for any writer who wanted to use those characters to bring them back with half a line of explanation.

If I wasn’t writing Zemo, though (or was just doing it briefly), I wouldn’t bring the (ugh) Baroness Zemo on stage for the purpose of killing her. I’d just leave her alone.

If you don’t want to do vampire stories you don’t have to. Killing them all off is — aside from a fun event — mainly an attempt to prevent others from doing vampire stories, which, honestly, if you’re EIC you can do by decree. And either way, they’ll come back as soon as you’re not around any more anyway. Because other creator and readers like vampire stories.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Around that time, there did seem to be support for more “grounded” superhero (type) things (Dark Knight, Batman Year I, Swamp Thing, Watchmen, the Wild Cards novels).

The problem was that these particular applications of that trend were (perhaps) less interesting or more derivitive.

The “White Event” is not unlike the release of the ‘Wild Cards Virus” in 1946 NYC in the Wild Cards novels, a discrete event where everything changes.

However, in the Wild Cards novels. the transformational event has stakes (the vast majority of people who catch the virus die or are horribly mutated and a very small number gain beneficial mutations) and the events in the novel have a context that dovetails with actual history (the dawn of the Atomic Age and the Cold War).

The “White Event’ has none of that,

Jim Shooter was a brilliant editor, no less than his mentors. Stan Lee and Mort Weisinger, were, But 1986 was probably not as favorable time to launch something new as the late 1930s or the early 1960s had been. Things were more controlled and more corporate, by 1986. Budgets were less shots in the dark,

LikeLike

“Hey, let’s create a shared universe like the Marvel Universe, but with less cool stuff in it!”

Not really the best way to go about starting something.

I mean, vampires, the Savage Land, magic…these are good things to have in a superhero shared universe. Stripping them out made the Marvel Universe less than it was. As big event stories, “Kill all vampires” and “The Savage Land is being destroyed” are cool — but part of why they’re so cool is that they have vampires and the Savage Land in them. They’re literally stories about the things you’re saying don’t belong.

It’s certainly possible to make an interesting universe without those things, but trying to throw them out of the Marvel Universe is a terrible idea, and predictably didn’t work. Though they made for popular event stories. Just not permanent changes.

The New Universe struck me as a good marketing/publishing idea that never got the content. Whatever it should have been, Jim and crew frittered away the time and at least some of the money making big announcements with a splashy graphic but didn’t nail down the ideas that’d go into the books, to the point that it felt like half the line was made of concepts Archie Goodwin slapped out overnight at the last minute — and they read like it, too.

The restrictions all just seemed to make it harder to make the stories exciting and commercial (not impossible, but harder), and the insane churn of freelancers prevented most of the ideas from being developed well, since the creative teams kept getting replaced. The strongest books, creatively, were the ones that kept (or found) consistent creative teas, but whatever chance they had was dragged down by the failure of the rest of the line.

It’s a shame. It was a terrific opportunity to create something effective and lasting, and while it’s true that Marvel’s top talent already had gigs that were paying them well, so dropping a well-paying book for a new launch wasn’t as attractive as it could have been, that doesn’t mean they couldn’t have lined up a slate of creators who knew how to make comics but weren’t already booked up.

That, however, would have needed development time, and would have been best done by creating books built around the creators’ strengths and interests, rather than making up a bunch of ideas the EIC liked (or would at least tolerate) and then finding warm bodies to write and draw someone else’s vision.

And yes, most successful shared universes grew form one of two books rather than being an insta-line, but 1986, at Marvel, was perhaps the best time ever for an insta-line — before people had become exhausted by them, and with the support of the most successful comics publisher in the US.

Jim’s ideas for a more “realistic” world could have worked, too, but I think a world like that would have been best pitched at older readers who’d get into the logic of that and be fascinated by the worldbuilding, rather than at younger readers who didn’t give a shit about whether the world held together scientifically.

But Jim wanted the more sophisticated world, aimed at younger readers, and he wanted the creators to do top-notch work not only on ideas they hadn’t created and didn’t grow up loving, but in editorial directions they largely didn’t like and weren’t natural to them. And it was, unnecessarily, a rush job to boot. What a mess.

It would be a blast to do a project like that well, but the time for something like that (and the support) is long gone.

I also think they needed to come up with a better name. “New Universe” is great for a launch, but if it lasts, you’re going to be stuck with that branding after it’s clearly no longer new.

I agree that the editorial rules of the NU presaged the various lines Jim launched thereafter, but I think it’s also interesting that the difficulty of keeping steady creative teams (or, perhaps, thinking they weren’t necessary) was part of those lines, too, though not to the drastic extent of the NU.

Everybody makes mistakes. But the NU was a pretty spectacular missed opportunity.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I can’t argue with any of this. I have no idea how Jim Shooter reacted to the massive failure of the New Universe, but I do wonder if it did shape his approach to later co-creating the Valiant Universe a few years later, because that was *so* much better, a genuinely great group of comic book titles set in an interesting world, and a huge success both creatively & financially.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Jim was not pleased, & the Valiant universe was helped considerably by the creative input of Bob Layton & Barry Windsor-Smith. (If I remember correctly, Bob’s official title at the company – which he co-owned w/Jim & several others, which became quite an epic tale of its own – was creative director.)

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m sure it did shape his approach to creating the Valiant line, which was much better thought out to begin with and better managed, though it didn’t last (lasted longer than the NU, though!), had a lesser version of the inconsistent-creative-teams problem, and from the outside it looked like the end came due to disorganization and internal acrimony.

For all that, though, it was a very good example of how to build a line, at least at that time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Valiant’s demise was a product of its own success, strangely enough. When Jim was ejected sales were still strong enough that Blockbuster was eager to buy it for a LOT of money; why that fell through & Jim’s departure are heavily intertwined. But then it got hit, as every company (inc & maybe esp Marvel) did, by the speculator collapse of the mid-’90s, but sales were still strong enough they managed to cash out to Acclaim. (The money Bob Layton made off it helped finance Future Comics a few years later.) Problem w/Acclaim buying it was the same as the problem faced by virtually every company bought by a larger corporation, esp. one with little knowledge of that particular field: Acclaim wanted to make back their investment ASAP, which became very difficult (I don’t know that they ever did) in a collapsing market. Relatively rapidly, Acclaim decided continuing with the line was throwing good money after bad, & walked it down the chute into the stud gun. Like many companies, albeit with somewhat better product than many, Valiant lived by the speculator market & died by the speculator market.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I also think Shooter made a good call with Valent by using established IP (Turoc, Dr Solar, and Magnus) as part of the Valiant world.

it was not all-new . . . .

LikeLike

I think that was a big help at Valiant, since they didn’t have much of a track record, so having some established characters helped. I don’t think they were needed in the New Universe, where newness was part of the appeal and they had the Marvel name (and sales machine) behind the imprint.

Similarly, Eclipse got more mileage out of launching AIRBOY and MIRACLEMAN than they would have gotten with all-new characters. It helps to have something to stand on, whether it’s an established property, a creator’s reputation, socko art, or whatever else you can muster.

LikeLike

People tend to forget that Valiant actually started out publishing wrestling comics. (I forget whether they were WWF or WCW.) I know these were to some extent forced on Jim by his backers, b/c they wanted the company publishing known properties. (Who lined them up for Valiant I couldn’t say.) I don’t recall whether they did okay for the company or not; seems to me that line didn’t go on all that well. The old Gold Key franchises – Solar/Magnus/Turok, if I remember correctly – may likewise have been a market hedge. But, as Kurt mentions, if they were, it was a fairly smart move.

And, no, the New Universe had the Marvel name behind it, & it was still marginally in the era of the Marvel zombie, so it didn’t… well, given the final result, perhaps it could’ve used some pre-established property but I’ve no idea what the possibly could’ve been. Which at one point was a pretty real thing for a lot of Marvel fans, but the direct market killed it by allowing Marvel to publish so many titles buying all of them was virtually impossible (& then you dump a whole new universe on top of it). Once it became impossible to maintain a “complete” collection, the concept of the Marvel zombie eroded to the point where virtually no one even makes reference to it anymore… (Plus the direct market opened a lot of readers to the idea there was something to comics besides Marvel, that had an effect as well, with Image perhaps dealing the death blow, no pun intended…)

The problem with most prefab universes is characters in them are created mainly to fill existing marketing niches, not because anyone felt any great creative need to create them, & they often smack just too overtly of corporatethink…

LikeLike

Valiant started out publishing a bunch of Nintendo comics, LEGEND OF ZELDA and the like. They had the WWF, but got MAGNUS, at least, out before any WWF books, if I recall correctly.

But yeah, they started out with licensed books. I don’t know if they’d have built out a Nintendo universe or a WWF universe alongside the superhero/adventure books, if those books had showed staying power, but I tend to doubt it — Shooter, Layton and Windsor-Smith clearly had their focus of interest. But they might have brought in some nice cash to help things get going.

I think they went after the Gold Key books because they had enough cachet to get them some ink, and that’s a big help, even if a large portion of the audience doesn’t remember those characters. The comics press and distributors and a substantial percentage of the retailers do, and that counts for a lot. It’s not the easiest foundation to build a universe on, since those three licenses all take place in different time periods, but Jim & crew made it work (Turok didn’t get launched until after much of the present-day line was rolling). They might have been better off with a different license, if a good one was available — I think the THUNDER Agents had failed too recently (and may have still been tied up somewhere or having legal fights), DC had bought the best of the Charlton characters, I’m not sure what else was out there that’d have made a splash.

So they worked with what they could get. And I don’t know who was coming up with the launch stunts, but they were very good at it.

And I don’t think the New Universe needed Marvel characters to launch it — I think first issue orders on those book were really impressive. It’s just that too many of the books weren’t good, and even if they had been, the creative teams kept changing. Having Spider-Man and the X-Men show up early, like Superman did with Captain Carrot, might have helped some, but I don’t think they needed greater incentive to get eyes on the books. They got that. The books just didn’t have staying power, and guest-appearances by Marvel stars would only have disguised that briefly, and would have violated the spirit of what Jim wanted to do, whether what he wanted was a good choice or not.

From my viewpoint, having done a superhero book at Eclipse shortly before the launch of Valiant, it was Valiant that broke the superhero fan’s allegiance to Marvel and DC for their super-product, and Image, as you say, made that break permanent. Although it does seem to have healed up a lot, in the decades since — launching costumed superheroes outside of the Big Two seems like an uphill battle again. Then again, launching almost anything, at the Big Two or beyond, seems like an uphill battle these days.

LikeLike

Martin and Chip Goodman’s Atlas “Universe” was probably handicapped by the lack of logical “team-ups” within the universe for comics coming out in 1974-’75 (where DC and Marvel had both been doing that sort of thing for 15 years or so).

I think Shooter did better in crafting the Valiant universe, where everything came out of the “Unity Event.” Something that seemed more grounded and to have more stakes, like the release of the Wild Card Virus in the Wild Card novels and unlike the “White Event” in the New Universe comics.

It was both solid storytelling and smart marketing.

The fact that Chaykin’s The Scorpion (Moro Frost/David Harper) was apparently immortal might have been the thing that could have tied the Atlas books together He could have done contemporary super hero Team u[s with The Destructor, Tiger-Man and The Phoenix and met the Western and WWII characters in their own times. It was an open enough concept, that he also could have met Iron Jaw and Planet of the Vampires in the future. (Chaykin dropped the concept for his later Marvel hero, Dominic Fortune, but it would have worked in its original setting.)

I wonder if Shooter and his crew actually factored that into they creation?

LikeLike

Did any of the Atlas/Seaboard characters meet? I’ve never thought of that line as a shared universe, because I don’t remember any sharing.

If there was some, and I’m just not remembering it, I don’t think there was enough to establish a line-wide universe.

And I doubt the Valiant guys took many lessons from Atlas beyond “Don’t do that.” There’s more than enough connection between the past, present and future in the Marvel Universe to show them how to connect them up; it’s just tricky to start with such separated elements.

LikeLike

You don’t remember it being a shared universe b/c it wasn’t one. Seaboard/Atlas didn’t copy that aspect of Marvel (& its universe was much less of a marketing focus in the ’70s than its brand was, while DC’s “universe” hadn’t really coagulated across the line then; there were character crossovers, & JLA, of course, but the editorial offices & most of the titles operated more or less independently, & DC titles well into the ’80s showed little interest in coordinating with others & many books introduced showed little indication of a shared universe) likely b/c Martin Goodman was behind it & Goodman’s publishing instinct had always been to figure out what was selling then flood the market with as many duplicates as possible. On launch the Atlas approach was to tick as many market niches as possible, not to create a “universe.” Even though Marvel & DC were both employing them to varying extents, “universes” was still considered largely a fannish notion through most of the ’70s, embodied in things like Mark Gruenwald & Dean Mullaney’s Omniverse fanzine. It only really took root as a marketing ploy in comics in the ’80s…

LikeLike

I would expect that, had the Atlas books lasted, the characters would have started meeting — at least some of them — because TIGER-MAN VS. BOG BEAST! is promotable, as long as anyone cares about those two characters.

But they never got to that point, and they didn’t really even nod to there being any connections, to my memory. Heck, they barely acknowledged that the characters were the same people, issue-to-issue…

LikeLike

Undoubtedly, Atlas would’ve gone that way, at least to some extent. Like I said, Martin Goodman made his money spotting & mimicking trends. (JLA->FF is a good example.) If he saw Marvel getting serious traction off superhero teamups & a shared universe, he’d had Destructor Team-Up or Tales Of The Atlas Universe out in a hot New York minute.

LikeLike

Re: Atlas continuity– I doubt that Martin Goodman ever had any inkling as to how important the “shared universe” thing had been for Silver Age Marvel. The entire aesthetic of Atlas (if one could call it that) was about the same thing Goodman had usually promoted in the 1940s: lots of books to dominate shelf space. Even the shared-universe stuff from Golden Age Timely probably mostly resulted from creators being playful with Timely properties, such as the big forties crossover everyone remembers, Super Rabbit and Widjit Witch…

LikeLike

By 1986, after about 16 years of collecting many Marvel comics regularly (irregularly from about 1969 to 1972, more regularly starting in 1973), I found myself buying a lot of titles that I didn’t have sufficient time or even interest in reading and drastically cut down on my purchases, while at the same time I came across new titles that I really did enjoy, such as Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing and Miracle Man and then Watchmen. I did love Miller’s return run as writer on Daredevil as well as Simonson’s run on Thor but I mostly gave up on other Marvel titles, although I did get the Englehart/Rogers run on Silver Surfer and stuck with that until a bit after the 50th issue.

I vaguely recall trying out at least a couple of the New Universe titles, but they bored the hell out of me and that was that for me. In retrospect, I can kind of sympathize with Shooter’s intent, but if he truly thought it would be commercially feasible to end the Marvel un/iverse as it stood in 1986 and launch an entirely new line starring far less fantastical characters, he must have been out of his mind. Mainstream comics fans tend to love the fantastic and bizarre with a touch of human realism. Most aren’t genuinely interested in the “world outside their windows” – they may prefer something that sort of resembles the world outside their windows but is nevertheless a lot more exciting and with characters who may be utterly bizarre but still reasonably relatable. That was the key to the success of characters like Ben Grimm and Spider-Man — yes, they had very bizarre aspects and powers, but they were also written as characters readers could sympathize with and relate to, despite not being covered in rock-like scales or being able to climb walls and swing from webs of their own making. What Shooter tried to do might have worked for an indie company on a shoestring budget but in which the creators had full creative control over the characters and the capacity to come up something unique enough to attract at least some attention and, if they were successful enough to keep going, gradually build up a loyal audience. Dave Sim did that with Cerebus. Wendi & Richard Pini with Elfquest. And several other creative types have had similar success over the decades since. But, of course, Shooter would never have approved of Cerebus and Elfquest because they didn’t fit within his restrictive demands for “real world” comics. Well, Harvey Pekar had that down pat with American Splendor, which I also came to love when I discovered that, but again that was the product of Pekar’s unique outlook and vision and the talents of his many collaborators, including Robert Crumb. And while American Splendor did well enough as an annual indie mag to keep going for decades, it wasn’t the sort of great financial success that enabled Pekar to quit his day job before he qualified for retirement.

Anyhow, can’t say I was the least bit surprised that the New Universe proved to be a fiasco. A variation of the Atlas fiasco launched by Martin Goodman a decade earlier but similar in astonishingly shortsighted thinking in trying to imitate what Lee, Kirby & Ditko, et. al., did rather haphazardly between late 1961 and early 1965, establishing what was essentially a new comics universe, albeit with roots in the elder eras of Timely/Atlas, but with entirely new outlooks and storytelling techniques that built up an ever-expanding fan base.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“But, of course, Shooter would never have approved of Cerebus and Elfquest because they didn’t fit within his restrictive demands for “real world” comics”

Marvel published both Cerebus and Elfquest during Shooter’s tenure.

LikeLike

Marvel never had anything to do with publishing Certebus, which was entirely self-published by Aardvark-Vanaheim. Elfquest was original sefl-published by Wendi & Richard Pini’s company, WaRP, but Marvel did publish colorized reprints of Elfquest from 1985 – ’88 under its Epic line. Marvel did threaten to sue Dave Sim over a parody of Wolverine, and Claremont included a parody of Cerebus in his X-Men run, but that was about all Marvel had to do with Cerebus.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Original full-color Cerebus stories were published in Epic Illustrated #26, 28, and 30. Cerebus in EI was promoted with a full-page house ad in other Marvel publications.

Epic editor Archie Goodwin did have more autonomy with EI than the other Epic Comics. Shooter had to approve every Epic Comics series and graphic novel for acquisition, so he was clearly on board with Marvel publishing Elfquest. He is listed as a consulting editor on the issues. However, I believe Goodwin could publish material in EI without clearing it with Shooter first. But I don’t believe he could have gotten a house ad published in other titles without Shooter’s O. K. Shooter was on board with publishing Cerebus, too.

LikeLike

There was also the much talked about but ultimately stillborn X-Men/Cerebus crossover.

LikeLike

I’d’ve LOVED to have seen that X-Men/Cerebus crossover. Not the product – couldn’t care less (not a slight on anyone who could) – but the mechanics of the project. Would’ve been a HOOT!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I remember seeing Dave at a Toronto store signing in 1983 and asked him what had happen with it and he said “The problem with working with Chris Claremont is you don’t so much co-plot as take notes,” which said to me that Claremont tried to take total control of the project, something Dave wouldn’t have let happen on his worst day. Personally, I’m still astounded it ever got beyond the post con bar conversation stage. Somewhere around here I have the Cerebus fan club newsletters cover the progress, such as it was.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It promised to be fun.

I could see a Cerebus-Wolverine stand-off being especially entertaining.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great start, looking forward to hearing more.

LikeLiked by 1 person