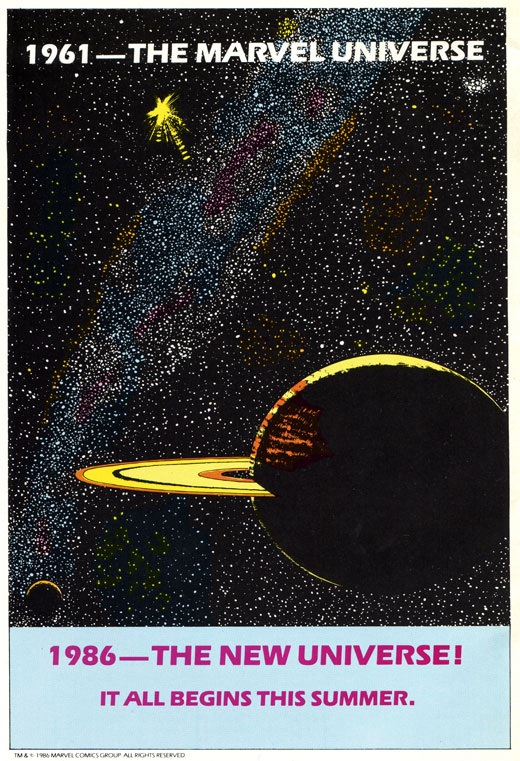

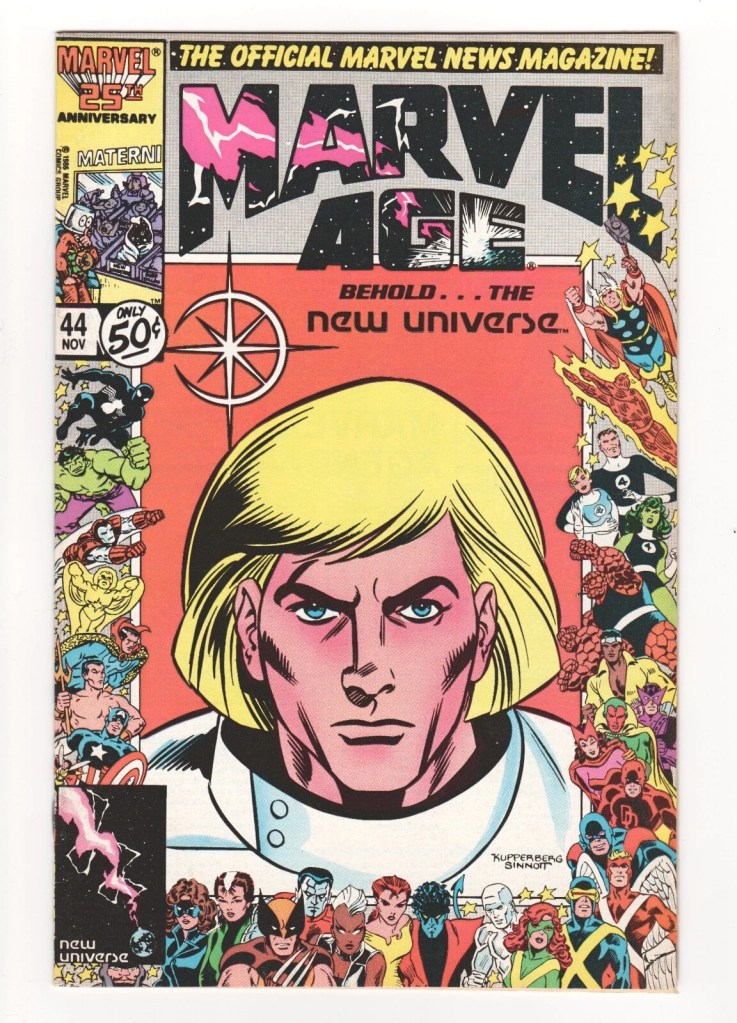

The New Universe was a bit of an epic fiasco in the history of Marvel Comics. it had been conceived as a way to mark the company’s 25th Anniversary as a popular publisher. Instead, it turned out to be an almost-instantly stillborn blemish, a complete creative misfire that was reviled and derided by the fans of that era. And yet, looking back at it, especially in the context of what came thereafter, it’s easy to see the potential that existed there for something pretty novel. There were some good bones in the New Universe, even if they never quite reached the point of being a skeleton that could support a publishing venture. So over the next couple of weeks, we’re going to be taking a look at the eight New Universe launch titles and seeing what can be discerned from them.

The New Universe was the brainchild of Marvel Editor in Chief Jim Shooter. And in fact, in certain circles, it was referred to as the Shooter Universe. Having stepped into the job of spearheading Marvel Comics in the late 1970s, Jim had spent a bunch of years reversing Marvel’s fortunes. He created an editorial structure that allowed for meaningful management of the workload, began to institute stronger emphasis on the fundamentals of storytelling, and expanded Marvel into the direct market in a meaningful way. But having set the ship aright, Jim was increasingly becoming disheartened by aspects of the realm over which he had jurisdiction. There were any number of aspects of the Marvel Universe that he felt were implausible or downright silly. he believed in an ordered universe, and so he strove to get rid of those elements that weren’t to his liking. At his direction, Roger Stern produced stories that eliminated all vampires from the Marvel Universe, for example, and another in which the Savage Land was destroyed. But this was like putting a band-aid on a gut wound. So when conversations rolled around to what the company should do for its impending 25th Anniversary, Jim suggested that they end the current publishing line, bring all of the storylines to a conclusion, and then for the anniversary re-launch the entire Universe again at square one. Only this time, with all of the elements that he didn’t favor left by the wayside. This initiative was internally referred to as the Big Bang. In these days of constant relaunches and continuity reboots and alternate Ultimate and Absolute Universes, the Big Bang doesn’t seem all that provocative. But at the time, it was a radical idea.

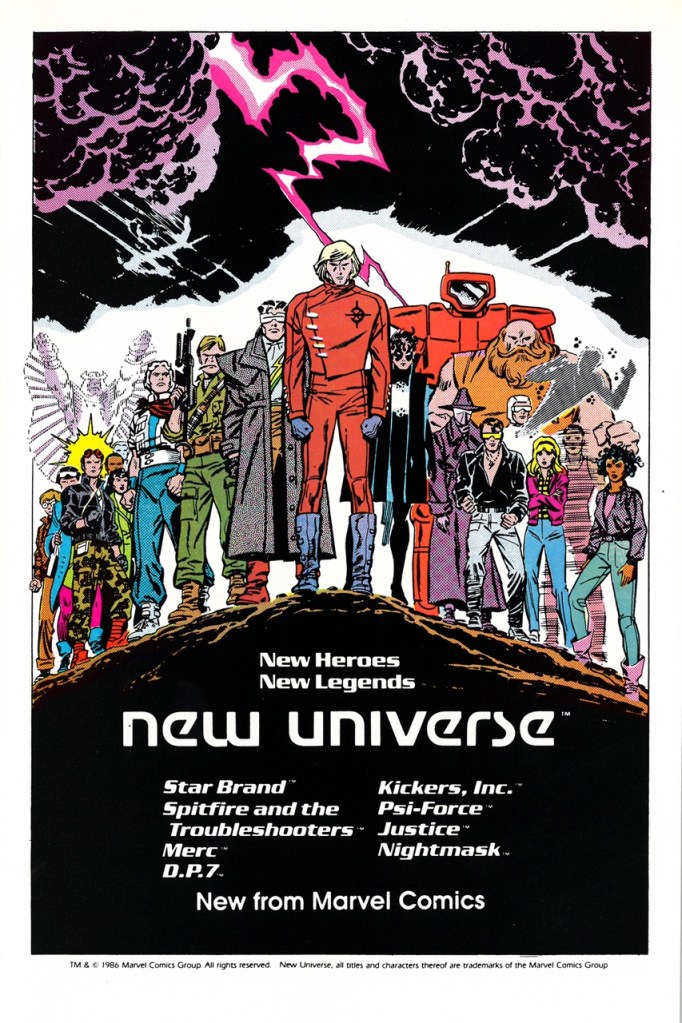

The problem with the Big Bang initiative was that Shooter had done his job too well. The Marvel line was insanely profitable, and the powers-that-be saw nothing but risk in the prospect of shutting it all down and restarting it anew. Additionally, there were several key creators and editors who weren’t keen on this plan, and they took their complaints (overtly or not) to the fan press of the day, who made a meal of Shooter’s plan. So the Big Bang wasn’t going to be a thing, and yet an Anniversary initiative was still called for. Stymied to a certain degree, Shooter suggested that he and his team do the next best thing: produce an entirely new universe of new titles and concepts, one that would be more in keeping with the rigid storytelling logic that he was after. A bunch of rules were outlined for the new effort to guide creators in coming up with properties for it. The New Universe was intended to be “The World Outside Your Window” as the tagline put it, a more realistic venture that was meant to be taking place within the real world. Accordingly, there wouldn’t be any sorcery, no alien life forms, no alternate dimensions, nothing implausible. There would be a single source for all of the change that happened in the world, the “White Event” in which the entire planet was mysteriously enshrouded in bright, white light for a minute, after which beings with superhuman powers would begin to emerge. Even skin-tight super hero costumes were frowned upon; any distinctive garb that the characters would wear had to feel like something that a person in the actual world might be able to put together. The line would also function in real time, just like the lives of its readers, meaning that in practice a month would go by for the characters in-between every issue. And at least at the outset, nobody was allowed to do anything so massive in their storytelling that it would change the state of the world, so any superhuman activity had to stay below-the-radar and not show up on news broadcasts and the like. Most of these guidelines would be bent if not outright broken as the line got started, but in the development stage they felt a bit like a straitjacket to some of the creators who were approached to do work on the new books.

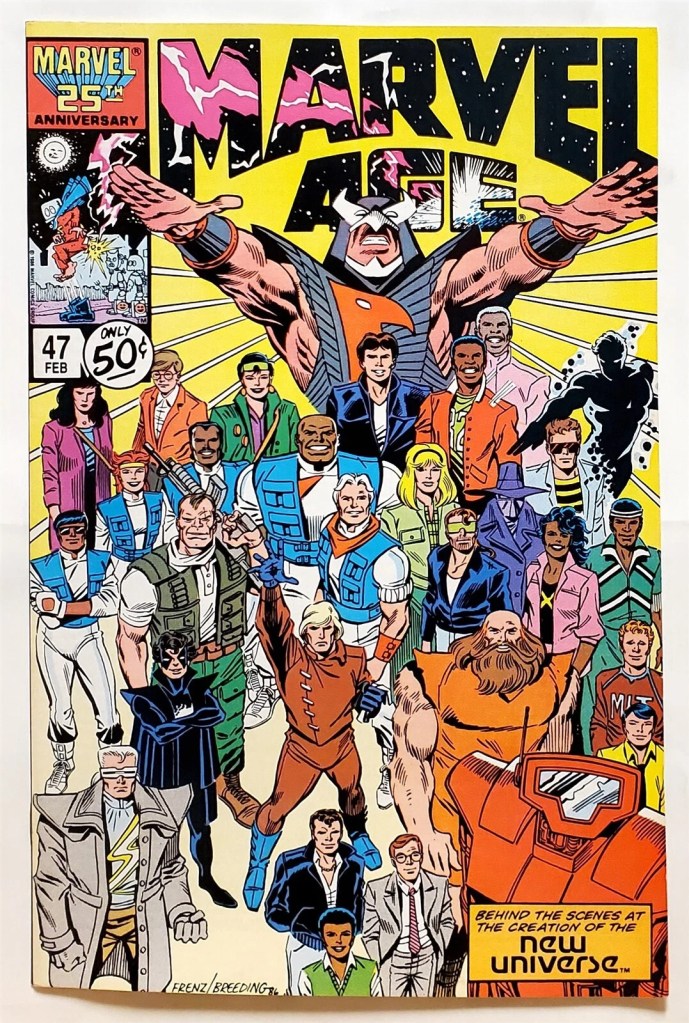

There were other problems as well. for one thing, by the mid-1980s, the battle for creator rights had been going on for a while, and most creators were well aware that anything they created for Marvel under these circumstances would become the property of the company. Most of the more popular creators were unwilling to relinquish their rights to any characters that might prove to be successful. Additionally, the incentive system that Shooter had helped institute meant that those working on popular titles made a ton of extra money in sales incentives. The new titles were untested and untried, so it made more sense for popular creators to remain on X-MEN and AMAZING SPIDER-MAN and the like, where their ancillary income was assured. what this amounted to is that, while the New Universe project was embarked upon with visions of top SF authors coming on board to craft a fully-plausible alternative speculative fiction universe, in practice the New Universe books wound up largely being the creations of editors working on staff (some of whom didn’t even directly write or illustrate the ideas they had come up with.) Creatively, it proved to be difficult to get creators to sign on board, which meant that the launch was fielded by mostly a collection of competent journeymen who weren’t especially popular in the Direct Sales marketplace as well as those who were just starting out and were willing to work on just about anything. The development time had eaten up a ton of lead time as well, for varying reasons, so the books all wound up operating under the gun. Pretty much every title was forced to rely on fill-in creative teams to one degree or another within their initial spate of issues.

Additionally, this was 1986, considered a seminal year in the history of comics, and for good reason. Over at the competition, DC was fielding CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS, SAGA OF THE SWAMP THING by Alan Moore, THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS, WATCHMEN and John Byrne’s MAN OF STEEL Superman relaunch in this selfsame year. And the alternative press was also pushing the boundaries with exciting and more adult-reader-oriented titles such as AMERICAN FLAGG, LOVE AND ROCKETS, GRENDEL, CONCRETE and many others. And MAUS, the first volume collecting Art Spiegelman’s account of his father’s time in a Nazi concentration camp, was helping to redefine just what the medium of comic books was capable of, going on to win the coveted Pulitzer Prize. By comparison, the New Universe titles, steeped very much in Shooter’s approach regarding absolute clarity of storytelling at all times, felt staid and out of step with the industry. Even other Marvel releases of the year, such as Miller and Mazzuchelli’s’ DAREDEVIL: BORN AGAIN or Walt Simonson’s THOR, made the New Universe seem quaint and old-fashioned. Shooter had been trained in making comic books for relatively young readers and it’s an approach that he held to throughout his career, even as the audience for comics grew progressively older and more sophisticated. The New Universe wasn’t targeting older fans, it was attempting to connect with a new generation of young readers. Unfortunately, most of those young readers were more attracted to the tried-and-true Marvel titles that Shooter and his team were putting out, leaving the New Universe out in teh cold.

Ultimately, the New Universe failed to catch on with readers and with retailers, and it began to suffer from weak sales almost instantly. It became a bit of a black eye for the controversial Shooter, who was already under fire in the fan press for other matters. Within a year’s time, Shooter would be relieved of his editorial duties and fired from the company over which he’d presided, and the New Universe would pass into the control of other hands, primarily those of executive editor Mark Gruenwald. Half of the titles were given the axe, while Gruenwald and editors such as Howard Mackie tried to turn around the fortunes of the rest. It was a losing battle, and by the early part of 1990, the New Universe was no more.

The thing is, while he may have become overly didactic about what he wanted and he was never entirely able to get those creators and editors working on the titles to embrace what he was trying to do, the New Universe really does feel like a trial run for the companies and lines that Shooter would create after his time at Marvel. In particular, the Valiant line under Shooter feels like a version of the New Universe done properly–a consistent science-based shared universe in which a variety of characters have grounded, realistic adventures in a story-driven setting that eschews many of the trappings of typical super hero comics. And after his falling out with Valliant’s ownership, Shooter’s later efforts in building the Defiant Universe and the Broadway Comics Universe employ similar approaches. What this says to me is that the New Universe wasn’t intrinsically a bad idea, it simply didn’t come together properly as it might have done under different circumstances. There’s a world where it might have been able to make a go of it and become a success. And there are definitely some interesting ideas buried inside its old, forgotten pages. So while none of these comics is particularly great, they are all pretty interesting–as we’ll see over the course of the next couple of weeks as we essay them.

Ooh, fun! I’ll enjoy reading these! More than I’ve ever enjoyed reading the New Universe comics, probably. I’ve always thought it was a good idea, just done badly…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really enjoyed DP7 and Star Brand but pretty much gave up on them after what felt like a very mean spirited revamp.

LikeLike

Has it been nearly 40 years since the New Universe first launched? One of my roommates and I were avid comic collectors at the time and dove into the New Universe with both feet. However, with the exception of Star Brand for me and DP7 for him, we dropped every title after their debuts. The additional background information helps explain a line of comics that had us wondering what Shooter was thinking. I didn’t last beyond #3 with Star Brand – although I returned when John Byrne had his more vengeful take on the character. I purchased the graphic novels that attempted to bring some life to this struggling line, but was long gone with it ultimately faded from their line,

Given that it has been four decades since the New Universe’s launch, I definitely look forward to Tom’s upcoming reviews.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The basic problem with the New Universe is what I call the “Instaverse syndrome.” Rather than starting with one or two titles, like Shooter did with Valiant, tossing out 8 or 10 new titles all at once. This mistake was endlessly repeated over the course of the 90s. DC also has this problem with their events, where rather than launching one or two new titles, it’s 5 or 6, of which inevitably only one survives, which I call the “Spaghetti syndrome:” Throw it all against the wall and see what sticks. 😉 That being said, I’m pretty sure I bought all the number 1’s, except the Kickers Inc. as the football thing was a nonstarter for me (See also: NFL SuperPro,) but didn’t stick with any of them beyond Starbrand. I did end up picking up Justice after Peter David took it over and revamped what was had been the title that instantly demolished “The “World Outside Your Window” concept. I’m hoping you’ll be talking about the weirdness that happened with the NU in Quasar, not to mention the better stories in Exiles and Avengers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“So while none of these comics is particularly great, they are all pretty interesting” I would consider that a charitable assessment, to put it mildly. With most of the books, blank pages would have been equally interesting.

I think this kind of thoughtful, rational, what’s-plausible approach runs against what most of us read comics for (I will freely admit I have not taken a survey to confirm this). Also Shooter’s approach sounds like a familiar problem: creator feels frustrated working on a book, decides the problem isn’t them, it’s that he has crap to work with. Clearly a massive reboot will fix the problem! It’s akin to a point one of your earlier posts made about editors stuck with books they aren’t sympatico with.

All that said, I look forward to your analysis. For instance I’d vaguely heard Shooter had some kind of Crisis-like reboot in mind but never any details

LikeLike

I’ve often wondered how professionals in the comics industry view AC Comics. Even thought (I think) they’re still publishing, I very rarely have heard of people in comics refer to the company or their titles.

LikeLike

A lot to go through here:

“So when conversations rolled around to what the company should do for its impending 25th Anniversary, Jim suggested that they end the current publishing line, bring all of the storylines to a conclusion, and then for the anniversary re-launch the entire Universe again at square one.”

Shooter always insisted this was a brainstorm that never rose above the level of “chatter.” Marvel’s sales were fine. If it ain’t broke, you don’t fix it. The sales department and the distributors for the newsstand market, which at the time still accounted for the majority of Marvel’s sales, would have vetoed something like this the moment they heard about it.

“there were several key creators and editors who weren’t keen on this plan, and they took their complaints (overtly or not) to the fan press of the day, who made a meal of Shooter’s plan.”

Please name these creators and editors and the publications they went to.

With the latter, I know it wasn’t The Comics Journal or Amazing Heroes. I also cannot imagine any editor doing this, because attacking one’s employer in the press is a guaranteed way to lose one’s job. (Freelance creators at the time were given more latitude.) The only creator I know of who blasted the alleged “Big Bang” plan in the fan press was Doug Moench, and it was many years after Shooter had left Marvel. I should note Moench has a big grudge against Shooter. He also has a penchant for exaggerating and outright making things up with his recollections. Most importantly, he would not have been privy to any discussion of this sort inside Marvel. Shooter blackballed him from working on Marvel’s company-owned titles in 1982. The blow-up which led to that also apparently permanently alienated him from Mark Gruenwald and Ralph Macchio, seeing as how neither ever worked with him again.

“There were other problems as well. for one thing, by the mid-1980s, the battle for creator rights had been going on for a while, and most creators were well aware that anything they created for Marvel under these circumstances would become the property of the company.”

I don’t think this was a concern. Marvel began a character-creation incentive plan in 1982 that gave creators a financial interest in the characters they created going forward. To the best of my knowledge, Marvel creators of the time, such as John Byrne, Chris Claremont, Walt Simonson, and Louise Simonson, are still making money from it. If creators wanted ownership of new ideas, there was the Epic imprint and the graphic-novel line. I’m trying to think of a Marvel creator of the period who left a Marvel-owned title assignment to work on a creator-owned project for an indy publisher. (DC didn’t offer creator ownership at the time.) I’m drawing a blank.

Shooter said the problem the New Universe had with attracting top-tier talent was that the project had its budget substantially cut shortly before launch. They couldn’t afford to pay the higher rates, and had to go with less expensive talent as a result. That seems much more likely.

“Additionally, this was 1986…”

I fully agree the New Universe lacked the freshness of the titles you mention. But it’s probably worth noting Marvel was also doing its part in 1986 with cutting-edge publications such as ELEKTRA: ASSASSIN and THE ‘NAM, both of which outsold everything you mention except DARK KNIGHT and MAN OF STEEL. THE ‘NAM also got heavy mention in the “Comics Aren’t Just for Kids Anymore” newspaper articles of the time. MOONSHADOW wasn’t a big seller, but it rates mention in that company, too.

“It became a bit of a black eye for the controversial Shooter, who was already under fire in the fan press for other matters. Within a year’s time, Shooter would be relieved of his editorial duties and fired from the company”

Contrary to your implication, Shooter was not fired because of his editorial decisions or sales.

The New Universe’s failure notwithstanding, Marvel’s sales during Shooter’s last year there were the best of his tenure, and Marvel’s best year since World War II. Twelve established ongoing titles–I’m not including new-title launches or limited series–averaged unit sales of over 200,000 an issue. Five of those sold over 300,000 an issue, and two of that five did better than 400,000. In 1986, DC had no established ongoing titles that averaged over 200,000 an issue, and neither did anyone else.

Shooter was fired because administrative disagreements with Marvel president James Galton had made their relationship toxic. The last straw was when Shooter sent a letter to New World Entertainment, who had recently purchased Marvel, denouncing Galton and his ethics.

LikeLike

Word I had from contacts inside Marvel at the time the New Universe was concocted – I was living in Los Angeles by then & I never had this confirmed by Jim (he & I chatting was a pretty uncommon event even when I was living in Manhattan), so please take it as heresay – was that the NU titles would be so successful – b/c of the Shooter approach that would immediately be recognized by the audience as vastly superior to, as you mention, the sprawling, shambling “storytelling” of the then-existing Marvel Universe – that the sales of the regular Marvel titles would start to fail, & as each “Marvel” title was cancelled, a new New Universe title would take their place, until finally the New Universe had the only titles left & reigned supreme. By which point “Stan Lee Presents” would be replaced on splash pages by “Jim Shooter Presents.”

I’d say the main problems with the New Universe (which you cover pretty well, Tom, so this is an adjunct to your commentary, not a contradiction) were none of the concepts were especially original – to some extent it seemed like readers were being asked to give it a go not b/c the characters caught their imaginations but because the New Universe concept was all the rationale they needed – & very little of the development was especially exciting or eyecatching. There was nothing especially explosive or scene-changing about it, & that’s what it needed. Most other “new universes” pushed by any company since have faced, and fallen on, the same problems. I suspect much of the problem lies in the planning: everyone wants to be “Marvel” out of the gate, & the NU was no different, but Marvel wasn’t really Marvel for a LOT of years after FF#1, & virtually NONE of it was planned. It accrued pretty haphazardly – what, as you mention, Jim was rebelling against – but while I can see something thinking that a weakness of the MU, it was also its great strength. Creating your entire continuity ahead of time – which almost every intended “new universe,” even today, seems prone to (I know both Dark Horse’s “Comics Greatest World/Dark Horse Heroes” & DC’s !mpact Comics were bibled within an inch of their lives) – is a great way to sap huge amounts of energy out of the comics you produce. Near as I can tell, that’s exactly what happened with the NU, give or take a couple titles.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I remember when these came out. I was getting a little bored with a lot of the Marvel/DC output, so theoretically, a “fresh start” might’ve had some appeal. But as I heard more about them, and flipped through a couple, there was just nothing there to get excited about. I didn’t know about the behind-the-scenes factors that were undermining the line before it ever got off the ground; I just saw it as a massive misfire, and further evidence that Marvel Editorial was out of touch.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Never bought one… though I flipped through them on the stands when they appeared. It’s a puzzler why Shooter or anyone would think that a younger audience would glom onto books with less colorful characters with a more grounded real-world approach? It seems like a possible avenue to get new readers who are older ,and not inclined towards traditional super-heroes… but they probably aren’t searching the spinner rack.

Looking at the crowd of NU characters… they’re a pretty dreary looking lot. All and all it’s a pretty poor idea for a 25th celebration of Marvel Comics. Probably would have been cheaper to repair the rifts with the founding creators and move from there… which is how anniversaries normally work. Easier said than done I suppose.

It’s possibly a pretty good case study of a seasoned and talented pro (Shooter) perhaps not really understanding one of the major appeals of the product….Marvel Comics could be sloppy….and sloppy could lead to surprise and delight.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Hey, let’s create a shared universe like the Marvel Universe, but with less cool stuff in it!”

Not really the best way to go about starting something.

I mean, vampires, the Savage Land, magic…these are good things to have in a superhero shared universe. Stripping them out made the Marvel Universe less than it was. As big event stories, “Kill all vampires” and “The Savage Land is being destroyed” are cool — but part of why they’re so cool is that they have vampires and the Savage Land in them. They’re literally stories about the things you’re saying don’t belong.

It’s certainly possible to make an interesting universe without those things, but trying to throw them out of the Marvel Universe is a terrible idea, and predictably didn’t work. Though they made for popular event stories. Just not permanent changes.

The New Universe struck me as a good marketing/publishing idea that never got the content. Whatever it should have been, Jim and crew frittered away the time and at least some of the money making big announcements with a splashy graphic but didn’t nail down the ideas that’d go into the books, to the point that it felt like half the line was made of concepts Archie Goodwin slapped out overnight at the last minute — and they read like it, too.

The restrictions all just seemed to make it harder to make the stories exciting and commercial (not impossible, but harder), and the insane churn of freelancers prevented most of the ideas from being developed well, since the creative teams kept getting replaced. The strongest books, creatively, were the ones that kept (or found) consistent creative teas, but whatever chance they had was dragged down by the failure of the rest of the line.

It’s a shame. It was a terrific opportunity to create something effective and lasting, and while it’s true that Marvel’s top talent already had gigs that were paying them well, so dropping a well-paying book for a new launch wasn’t as attractive as it could have been, that doesn’t mean they couldn’t have lined up a slate of creators who knew how to make comics but weren’t already booked up.

That, however, would have needed development time, and would have been best done by creating books built around the creators’ strengths and interests, rather than making up a bunch of ideas the EIC liked (or would at least tolerate) and then finding warm bodies to write and draw someone else’s vision.

And yes, most successful shared universes grew form one of two books rather than being an insta-line, but 1986, at Marvel, was perhaps the best time ever for an insta-line — before people had become exhausted by them, and with the support of the most successful comics publisher in the US.

Jim’s ideas for a more “realistic” world could have worked, too, but I think a world like that would have been best pitched at older readers who’d get into the logic of that and be fascinated by the worldbuilding, rather than at younger readers who didn’t give a shit about whether the world held together scientifically.

But Jim wanted the more sophisticated world, aimed at younger readers, and he wanted the creators to do top-notch work not only on ideas they hadn’t created and didn’t grow up loving, but in editorial directions they largely didn’t like and weren’t natural to them. And it was, unnecessarily, a rush job to boot. What a mess.

It would be a blast to do a project like that well, but the time for something like that (and the support) is long gone.

I also think they needed to come up with a better name. “New Universe” is great for a launch, but if it lasts, you’re going to be stuck with that branding after it’s clearly no longer new.

I agree that the editorial rules of the NU presaged the various lines Jim launched thereafter, but I think it’s also interesting that the difficulty of keeping steady creative teams (or, perhaps, thinking they weren’t necessary) was part of those lines, too, though not to the drastic extent of the NU.

Everybody makes mistakes. But the NU was a pretty spectacular missed opportunity.

LikeLike

By 1986, after about 16 years of collecting many Marvel comics regularly (irregularly from about 1969 to 1972, more regularly starting in 1973), I found myself buying a lot of titles that I didn’t have sufficient time or even interest in reading and drastically cut down on my purchases, while at the same time I came across new titles that I really did enjoy, such as Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing and Miracle Man and then Watchmen. I did love Miller’s return run as writer on Daredevil as well as Simonson’s run on Thor but I mostly gave up on other Marvel titles, although I did get the Englehart/Rogers run on Silver Surfer and stuck with that until a bit after the 50th issue.

I vaguely recall trying out at least a couple of the New Universe titles, but they bored the hell out of me and that was that for me. In retrospect, I can kind of sympathize with Shooter’s intent, but if he truly thought it would be commercially feasible to end the Marvel un/iverse as it stood in 1986 and launch an entirely new line starring far less fantastical characters, he must have been out of his mind. Mainstream comics fans tend to love the fantastic and bizarre with a touch of human realism. Most aren’t genuinely interested in the “world outside their windows” – they may prefer something that sort of resembles the world outside their windows but is nevertheless a lot more exciting and with characters who may be utterly bizarre but still reasonably relatable. That was the key to the success of characters like Ben Grimm and Spider-Man — yes, they had very bizarre aspects and powers, but they were also written as characters readers could sympathize with and relate to, despite not being covered in rock-like scales or being able to climb walls and swing from webs of their own making. What Shooter tried to do might have worked for an indie company on a shoestring budget but in which the creators had full creative control over the characters and the capacity to come up something unique enough to attract at least some attention and, if they were successful enough to keep going, gradually build up a loyal audience. Dave Sim did that with Cerebus. Wendi & Richard Pini with Elfquest. And several other creative types have had similar success over the decades since. But, of course, Shooter would never have approved of Cerebus and Elfquest because they didn’t fit within his restrictive demands for “real world” comics. Well, Harvey Pekar had that down pat with American Splendor, which I also came to love when I discovered that, but again that was the product of Pekar’s unique outlook and vision and the talents of his many collaborators, including Robert Crumb. And while American Splendor did well enough as an annual indie mag to keep going for decades, it wasn’t the sort of great financial success that enabled Pekar to quit his day job before he qualified for retirement.

Anyhow, can’t say I was the least bit surprised that the New Universe proved to be a fiasco. A variation of the Atlas fiasco launched by Martin Goodman a decade earlier but similar in astonishingly shortsighted thinking in trying to imitate what Lee, Kirby & Ditko, et. al., did rather haphazardly between late 1961 and early 1965, establishing what was essentially a new comics universe, albeit with roots in the elder eras of Timely/Atlas, but with entirely new outlooks and storytelling techniques that built up an ever-expanding fan base.

LikeLike

Great start, looking forward to hearing more.

LikeLike