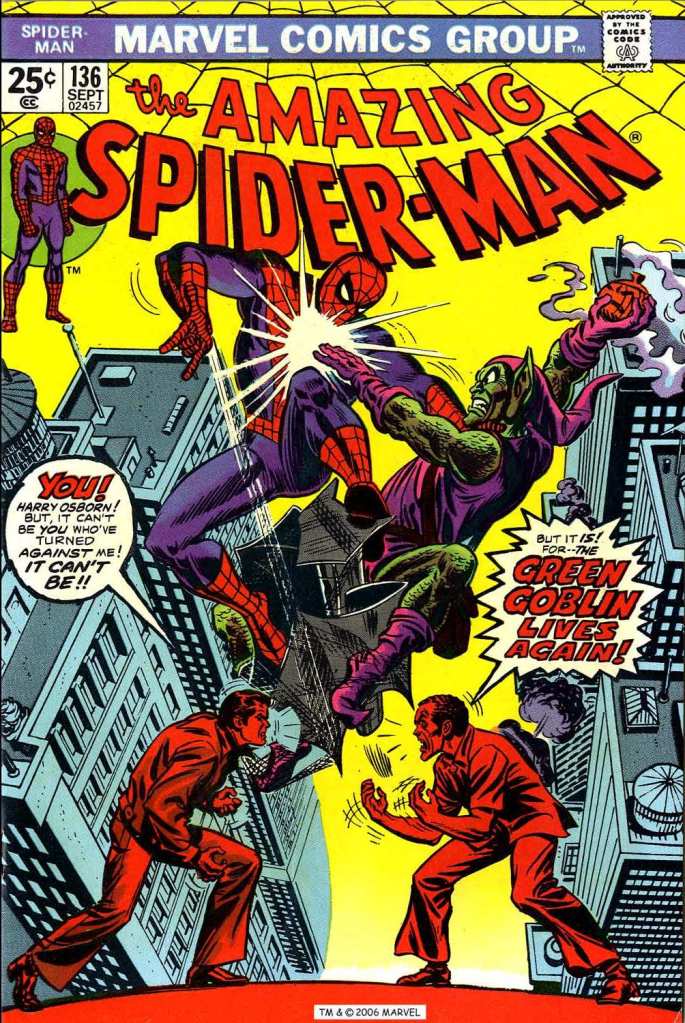

This issue of AMAZING SPIDER-MAN was another one that I read courtesy of my grade school friend Donald Sims, who lent me his copy for a day or two. Already by this time, the Green Goblin had become somewhat legendary as Spider-Man’s greatest foe, his reputation somehow enhanced due to the fact that he wasn’t around any longer. So this development, one that writer Gerry Conway had been building up to in the series for several months, seemed incredibly exciting to me–even though I knew in general already how all of this worked out. The great John Romita cover certainly does a lot to sell the momentousness of this particular issue.

I have a lot of fondness for the Gerry Conway era of AMAZING SPIDER-MAN, even though the strip during this period had only the loosest connection to the formative Lee/Ditko days of the character. Possibly because he was around the same age as Peter Parker when he was writing these stories, Conway’s Spider-Man always felt genuine to me. It was clear that he was trying to follow in the footsteps of Stan Lee, not by simply imitating what Stan had done, but by pushing things forward in new directions. Gerry did the same thing on FANTASTIC FOUR, but there his innovations felt counter to the appeal of the strip, particularly in the form of the marital strife between Reed and Sue Richards. But in ASM, Conway dedicated a good amount of time to building up Peter Parker’s burgeoning relationship with Mary Jane Watson following the death of his earlier girlfriend Gwen Stacy. Parker was more angst-ridden in a Woody Allen manner in this period, but that seems very 1970s to me, so it fit the times.

And Peter had good reason for his anxieties in this period, as Conway kept continually hitting him with one thing after another. Case in point: this issue opens with Peter and MJ returning to his apartment after a Sunday out doing things together. There’s a sense in-between the lines that this may be the moment when the two finally get together. But this lasts right up until MJ puts Peter’s key in the door lock, and Pete’s spider-sense goes off. And then, the apartment explodes, and MJ takes the brunt of the blast. With his usual sense of priorities, Peter cursorily checks to see if MJ is all right, then he races into the demolished apartment to grab and stash his spare Spidey outfit before the cops and the fire department can respond to the explosion. The man has priorities, and MJ doesn’t entirely seem to be one of them.

Hours later, after a grilling from the cops, Peter is still at the hospital when MJ comes around. Seeing her injured in the hospital bed conjures up memories of Gwen Stacy for him, which makes him think naturally of the Green Goblin. Clearly the explosive at the apartment was meant for him, and the Goblin was the only foe of his who knew his true identity. So Pete’s got a sinking feeling that he knows what’s going on here, as unbelievable as it may be.

Presumably to make the pagination work for the upcoming double-page spread, the first half of the two page THE SPIDER’S WEB letters page runs at this point. It was odd to find a Marvel letters page this early in the book, let along broken across the magazine, but I expect it was necessary in order to get the spread onto two facing pages.

And here it comes, the big moment! Leaving the hospital, Spidey suits up and heads over to the abandoned warehouse that Norman Osborn used as a base of operations when he was the Green Goblin. The place appears to be untouched, but Spidey realizes that the dust covering the place is actually the material used in films to replicate the look of dust. So he sets himself up in a web hammock to wait. And wait he does–until finally, in the dead of night, in this big two-page spread, the Green Goblin soars into the place in all his glory. It’s a great shot, one that would be pulled as pick-up art for licensing purposes, appearing on any products that featured the Goblin.

This, of course, isn’t the genuine Green Goblin, but rather his son, Peter’s roommate Harry Osborn. Having gone ’round the bend thanks to a bad drug trip and the grief from his father’s death, Harry worked out Peter’s true identity and adopted the Goblin identity to revenge himself on the man who killed his father. Now, Harry doesn’t have his father’s Goblin-serum enhancing his physical strength, yet he’s able to go one-on-one with the web-slinger anyway. This was a common thing in the 1970s, when writers would downplay just how strong Spidey really was. Either way, the pair engage in a multi-page pitched battle, one that Spider-Man is hesitant to go all-out in as he realizes that Harry is sick and not himself.

So ultimately, with the help of some drug-laced smoke, the Goblin defeats Spider-Man and is ready to lower the boom on him. But at that instant, like a reverse Parker Luck moment, the Goblin’s finger-blasters run out of charge, and so he’s unable to kill his hated enemy. So Harry flies off, threatening to put an end to Spider-Man one way or another–by killing him in a return match or by revealing his true identity to the world. And all Spidey can do is watch his former friend soar away. The final four panels of the book read as strangely to me now as they did back then. It’s the following day, and Peter is at the daily Bugle and pissed off. J. Jonah Jameson refuses to give him some time off, and Peter is so upset about this that he practically takes Betty Brant’s head off. I can remember thinking as a young reader that this maybe had something to do with the gas the Goblin hit Spidey with, especially as the final captions hint at there being something behind Peter’s bad mood. But nope, when I finally tracked down the second part, there aren’t any extenuating circumstances–Peter is just being an asshole here.

and since I showed the first half earlier, the final page in the issue runs the back half of THE SPIDER’S WEB letters page, including a huge ad for a couple of different Conan projects and the dreaded Marvel Value Stamp, this one of the malevolent Mole Man.

I wasn’t buying comics at this point in my college career, but I was peripherally aware of what was going on. I was tired of the on-again-off-again teasing of the Green Goblin. But what could you do, once you had revealed each other’s identity and killed him off? Fortunately, Roger Stern did know…

LikeLiked by 1 person

“This was a common thing in the 1970s, when writers would downplay just how strong Spidey really was.” True under Stan Lee, who had no problems with an ordinary thug like Man-Mountain Marko going toe to toe with the Webslinger. Perhaps everyone on Earth-616 is just stronger than we are.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think it was that the superheroes weren’t as strong as they’ve gotten since.

Lots of them used to be able to have a reasonably dramatic fight with normal thugs, even if they were capable of amazing feats of strength when they needed it. But once the Marvel Handbook hit, suddenly their strength level was quantified, and the fans expected them to operate at peak strength at all times.

And then we started to get stories revealing that the guys they were fighting had super-strength too, for one reason or another, and power creep — which, to be fair, had been a thing even before the Handbook — began to get more and more dramatic.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah… the Handbooks took a bit of zing out super-hero comics for me.

The strict ranking seemed at odds with how the stories always bent over backwards to leave the actual power differences between combatants within a given league somewhat vague. They broke an enduring genre rule that allowed us to previously enjoy Spider-man vs The Kingpin without thinking that Spider-man was really struggling to beat a guy who has less than 1/10th his strength.

LikeLike

There’s definitely been superhero strength increases over the decades, but Spider-Man’s powerset since the start has had super-strength far greater than human. I remembered these old writeups:

https://tombrevoort.com/2021/09/25/lee-kirby-the-character-write-ups-of-stan-lee/

The Thing: “One of the strongest mortals on earth. Can lift ten-ton weight.”

[Yes indeed, increases since then!]

Spider-man: “Has proportionate strength of spider. (Approx. a dozen times as strong as average healthy male)”

At 12x strength, he should wipe the floor with any unenhanced human opponent, even top-level humans such as Kingpin. Spider-Man also doesn’t seem to use his webbing as much as he should, as it’ll quickly immobilize any unenhanced human. I understand writers want a fistfight between a hero and a villain for the action. But it’s hard to suspend disbelief when the hero is doing something like throwing a manhole cover like a frisbee on one page, yet having trouble taking down an athletic human on another page.

LikeLike

Stan Lee had villains in a couple of stories chop through solid steel with no super-powers, just a black belt in karate. Which an ordinary human can’t do. Though I realize that’s because Lee approached martial arts as a super-power (all the fights in Avengers resolved because “Captain America taught me the secret of using my enemy’s strength against him!”).

LikeLike

Those ordinary humans just aren’t doing karate right.

If they knew how to do it really, really well, then steel has no chance against them. We just haven’t figured that out yet in our world.

Also, ants understand English.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And yet, the creators of these characters wrote and drew them in such a way that they were regularly presented as being in some peril when fighting groups of human assailants, or a single notably skilled/strong human assailant.

So rather than say the creators got it wrong because the numbers somewhere say X, it’s best, to my mind, to think the creators got it right, and what they show is how the characters work.

As such, maybe having 12 times the strength of a human isn’t the casual thing that post-Handbook readers tend to demand. Maybe that’s his top level at extreme effort, and it’s true when he’s thinking about how Aunt May’s going to die unless he lifts the Huge Machine, but it’s not his everyday level of activity.

Maybe if he accesses that level of strength now and again, he’ll be weak as a kitten from the effort, so it’s not easy and it’s not casual and it’s not something he accesses when he’s fighting a gang of thugs with tire irons.

And maybe what happens in the stories outranks the character write-ups, because that’s what happens in the stories, and that’s what we should base the portrayal of the characters on, not what it says somewhere that doesn’t match what happens in the stories.

The stories are what counts.

When readers look at the stories — especially the foundational stories — and say those stories are wrong and the data they get from power listings is correct, I think they’re getting it wrong.

And whether that data comes from the Handbook or from a backup feature somewhere or from Stan’s write-ups that he batted out as advice to animators, it’s always, always, always secondary to the stories, and if the stories show something other than what’s in the data, then the stories trump the data.

The stories are just plain more important than numbers on the side somewhere, and always should be.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I’m of the view that writers should “play fair” in the stories, which includes staying within rules long-established about a character’s powers. There’s wiggle room here, but there’s also the other direction of just ignoring too much. And from the start, Spidey has super-strength far, far, stronger than an ordinary human, “the proportional strength of a spider”. It’s even part of his theme song (“Is he strong? Listen, Bud. He’s got radioactive blood”). Putting aside the exact value, it’s clearly a large amount. Back in ASM#1, Spidey gets into a tussle with the FF, and easily breaks out of a containing cage, and tosses The Thing around without overly exerting himself. Now, as expert fighter characters often monologue, training, skill, and technique matter, aside from raw strength. But still, there’s strength differentials where the battle is almost certainly going to the strong. Given Spidey’s strength, plus enhanced agility, speed, and reaction time, he should trounce any non-superpowered wrestler or acrobat. Doing otherwise is just violating the premises of the characters, even if it makes for a dramatic scene. This isn’t overquantification, about “10 tons” vs some other number. It’s a basic qualitative difference, that Doctor Doom should trivially stomp a pack of squirrels.

There’s a great scene in the story A Death In The Family, where a very emotionally distraught Batman punches Superman in the face, and Superman is concerned Batman could have injured himself. I found it powerful, because the writer worked within the constraints. It showed how upset Batman was, because he did something so ridiculous. Yet it was dramatic action. But it had the expected consequences, in that an ordinary human socking Superman is only going to hurt their hand.

Yes, practically the sheer amount of stories needing to be written means keeping consistent isn’t going to happen. But plot holes are still plot holes, and people aren’t wrong for pointing out some of them make a story unreasonable, or even unsatisfying to those readers.

LikeLike

I don’t think something Stan wrote to animators that’s only public because someone found it and showed it around should trump what’s in the stories themselves.

I don’t even see any evidence that the animators followed it.

I can see the argument that everyone who’s got X amount of super strength should be an unstoppable tank, but I don’t agree with it, because (a) that’s not how they act in the stories and the stories are what counts, and (b) it’s boring.

Superman being concerned that Batman broke his hand is fine. Superman is an unstoppable tank, even in the stories. Though human villains can still get the drop on him with hi-tech weapons, which suggests his reaction time is highly variable.

But Spider-Man shouldn’t be Superman. He should be the guy in the stories, regardless of what some well-meaning person put in the handbook or in private notes to an animation company or wherever, without realizing it would make a percentage of fans start arguing that what’s in the stories must be wrong.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I referenced those writeups because I’d recalled them, and they were quantifications which were far earlier than the Handbook. Also, it does support your point about power increases, since Thing / 10 tons was top super-strength level (nowadays, that’s closer to a starter super-strength level). But even so, once more, Spider-Man was very very strong all along, from inception. I looked through a few initial issues for more story evidence:

AF15: “I crushed this steel pipe as though it were PAPER!” (page 4)Easily carrying a heavy fighter – “I have the speed, the agility, the very STRENGTH of a gigantic spider!” (page 5).ASM2: “My muscles are far stronger than an ordinary human’s!” (page 6)ASM4: “… if I get into a fight with a normal guy, I could PULVERIZE him!” (page 20)Annual1: “Having the proportionate strength of a spider, Spider-Man is one of the most powerful super-heroes! Only THOR, THE HULK and THE THING have greater strength!” (obviously that was then, but the point is he’s extremely strong).

This isn’t about mistakenly being thought to operate at all times with peak strength. Rather, it’s repeated over and over that the character is much stronger than human. Not a little stronger, but greatly stronger. Exactly how much is the quantification, but if someone can easily crush steel pipe, they just shouldn’t have trouble with a nonpowered human opponent. A writer can do that in a story, but again, in my view, it’s bad writing (which of course happens) because they aren’t “playing fair” to well-established rules.

LikeLike

Like I said earlier, I understand your argument, but any view that says Ditko and Lee (and Romita and Kane and Conway and Andru and…) got it wrong, over and over, is to my mind a bad view.

You have to find a way to reconcile the idea that he is that strong but that he can also be menaced by a bunch of gangsters with knives and lead pipes.

Because both of those things are evidently true. It’s right there on the page, and it’s there in the work of the creators who invented the character and invented the idea that he’s that strong. If you buy one, you need to buy the other. If you don’t, you can’t buy either, because they’re part of the same package.

Not everyone has to feel this way, of course, but no amount of “This scene says X and that scene says Y, so X is true and Y is false” will convince me. You could just as easily say that since the scenes say Y, then he’s not actually as strong as the X scenes say.

Me, I think X and Y are both true. Call it biorhythms, call it whatever. The creators got it right, not just half right.

And a happy Christmas to all, or at least a Merry Thursday.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I believe in two laws of superhero comics: 1) Hulk is strongest one there is, and 2) the Flash is the fastest man alive. However writers and artists want to interpret those is fine by me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The only rule I can think of I follow is that no inconsistencies or incongruities are important if I only think of them after enjoying an issue. If the story works with them then it doesn’t matter more than reading a good story.

LikeLike

Depends. I’ve read stories I liked and overtime the only thing I remember is OMG, that was so wrong.

LikeLike

I’ll add a couple more to that:

Captain America is the World’s Greatest Fighting Machine.

The Batman is the World’s Finest Detective.

LikeLike

It’s not just the handbook or the games. Based just on what we see in the stories, Man-Mountain Marko should be punching way out of his weight class. Kingpin too, but John Romita endows him with so much presence, I can buy it.

On the other hand, Barry Allen should have been able to take down his rogues easily 90 percent of the time, given how fast he can move (and without coming anywhere near an exhausting level of effort). But as you say, that would make 90 percent of his stories wrap up in two pages so I roll with it (as Roger Ebert used to say, “grant them the premise” if they can make a good story out of it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sometimes I think about what one can accept, even if it’s “wrong”, and what’s just going too far for suspension of disbelief. I speculate it has something to do with our intuitions. We don’t have much of a sense of the difference between being able to lift “10 tons” vs “30 tons” vs “100 tons”, even though these are massive. But we have a much better sense of the difference between “average human strength” vs “can throw you across the room without breaking a sweat”. This may be the root of the problem with Kingpin vs Spidey. Kingpin looks like he can swat Spidey, since intuitively someone with all his muscle would crush a nonpowered human of Spidey’s build. Thus there’s a strong temptation to write that, due to the dramatic way it looks on the page. But that grates on me since it’s so much a violation of the core aspect of “Spider-strength”.

LikeLike

Marko got retconned as part of a super-strength experiment by the Maggia, so he’s been retroactively made super-strong.

But he wasn’t, originally. He’s just been power-crept to match Spider-Man’s power creep. Back then, a really tough guy could do way impressive things, without needing powers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I didn’t have access to Gerry’s Spider-Man back then. I knew his DC stuff from a few years after that. I know he’s got a ‘storied” and lengthy resume, but nothing really clicked with me.

Some if the artists he worked with during that period at DC, Gene Colan, Klaus Janson, Don Newton, much of their work then is gold. I still look at a lot of it with awe.

LikeLike

Andru/Giacoia. So nice.

LikeLike

This was my first issue of AMAZING, although I had previously bought a couple issues of MARVEL TEAM-UP, and I’d seen the TV cartoon, so I was familiar with the character. Looking over the covers, it was apparently also the last issue I bought for a couple years. I remember liking the story, so why didn’t I continue? My guess is, I wasn’t able to find the following issue, and just gave up. I had a weird habit of doing that — if I couldn’t find the conclusion to a continued story, I would drop the book entirely. I can’t explain why, but it made sense to me at age 9. Years later, I would spend a lot of time and money catching up on back issues that I had passed by in my youthful fits of pique…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Seeing the art makes em realize Andru’s Goblin is my favorite of all time. Not a revelation? That I feel like Norman should never have been revived and the Goblin retired when Harry’s nutty shrink died.

LikeLike

Though I’m not a Conway fan, I like seeing Parker occasionally be an asshole and not apologize for it. I even think there was an off-and-on arrogance in the Lee-Ditko version.

LikeLike

Pride, and over-confidence…not arrogance…

LikeLike

Maybe a little self-pity, too. And aggressive towards weaker people. He inherently knew not to offend Jameson. So he took his bad mood out on someone weaker. Shows the human in superhuman. Hopefully he was much nicer to her next time & apologized.

LikeLike

I don’t recall reading this issue. I do recall that Spider-Man would lose some or maybe all of his powers. Perhaps a ReMasterwork will return these issues to print.

LikeLike

“Now, Harry doesn’t have his father’s Goblin-serum enhancing his physical strength,” IIRC Norman didn’t either — that was a retcon added later. In Lee/Ditko the green gunk made him nuts but not super-strong — he never goes toe to toe with Spidey in brute force but relies entirely on his gadgets and strategy (he ain’t even that good a fighter). If I’m wrong, I’m sure someone here will know it.

Also was Peter on staff by this point? Because he pointed out to Jonah years earlier you can’t fire someone who doesn’t work for you. Not that Jonah might not throw a fit anyway.

LikeLike

From those last four panels, I might have guessed that Peter was trying to put some distance between him and his supporting cast…in order to protect them in the event Harry tried to “spill the beans”… Am I right? (I never read the follow up…)

LikeLike