It cannot be overstated just how amazing an impact was made by writer Alan Moore on comic books. He came along at exactly the right time, just as the Direct Sales Market was making it possible to do comic book stories with greater sophistication for a somewhat older audience. It was a rare thing for a writer in comic books to become a super-star in this era–typically, it was the most popular artists who achieved that goal, though some of them did mostly write their own material–but Moore did it virtually from the moment he began working for DC Comics on SAGA OF THE SWAMP THING. During his time at DC, he wrote only three Superman stories, but all of them are acknowledged classics in the canon and have stood the test of time. And that’s ultimately because not only was Moore a consummate wordsmith with an understanding of plot, narrative and characterization, but he was also a huge fan of the characters and the material, having studied it from the inside out. His two-part “Whatever Happened To The Man of Tomorrow?” story in the final pre-reboot issues of SUPERMAN and ACTION COMICS is both an affecting love letter to the past and an example as to how such stories could be made contemporary and exciting without needing to throw out the strange aspects that made them interesting.

Moore came to write this two-part story circuitously. By the mid 1980s, DC was investing a lot of time and effort in streamlining their publishing universe, transforming it from a place with assorted multiple Earths into a more simplified continuity that integrated the best of everything in emulation of the Marvel model. Consequently, after CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS did that deed, DC intended to relaunch its flagship character Superman under the auspices of John Byrne, at that time just about the most popular artist in the field. As part of this rehabilitation process, editor Julie Schwartz, who had been putting together the Superman titles since 1971, would be handing them over to a new editorial team. So Schwartz was faced with the question of what to do with his final issues. Given that a new SUPERMAN #1 was being planned (with the current series about to be relabeled as THE ADVENTURES OF SUPERMAN with the next issue) Schwartz saw an opportunity. He hit upon the idea that his final Superman story should be treated as though it was the actual last superman story, wrapping up all of the outstanding business and providing a finale for fans of the earlier version of the character. But who to get to write it?

Schwartz’s first pick makes total sense: Jerry Siegel, the writer who had created the Man of Steel with artist Joe Shuster decades before. Julie had been on friendly terms with Siegel ever since they had both been science fiction fans in the 1930s, and so he approached Siegel with the idea. Siegel was interested in the offer, but ultimately he was uncomfortable with the paperwork that he’d have to sign in order to be set up in DC’s accounting systems as a contributor again. I suspect that, having been screwed by previous DC administrations, Siegel was concerned hat this whole thing was some manner of Trojan Horse to get him to sign documentation that would be detrimental to his settlement on the character. Whatever the truth, he and Schwartz couldn’t make it work. So Schwartz attended that year’s San Diego Comic Convention still needing a writer.

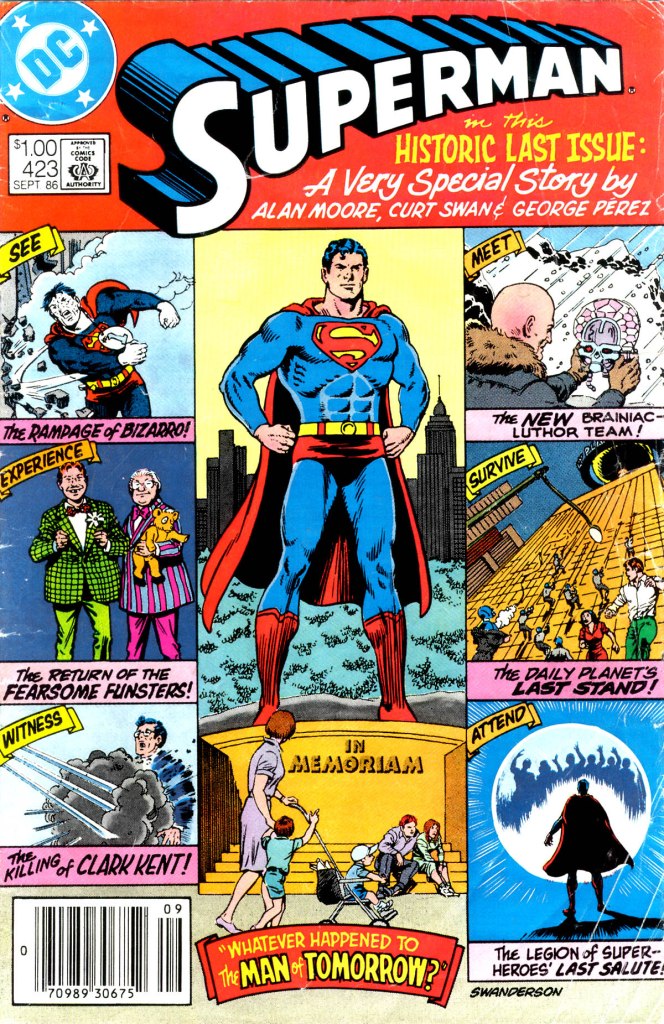

According to Schwartz in his autobiography, he had breakfast with Alan Moore one morning, the latter attending the show for the first time, and Moore reached across the table and grabbed him by the collar, indicating that he’d do Julie bodily harm if he hired anyone but himself to pen this final tale. It’s a good story, but one that’s no doubt become exaggerated in the telling. Either way, Moore was on board to write this concluding Superman two-parter. This was at a time when he was also concurrently writing both WATCHMEN and SWAMP THING, so getting him for this story was something of a minor coup. On the art side, Schwartz of course went with the character’s mainstay for the preceding two decades, Curt Swan. But he also did a bit of stunt casing on this first chapter, getting artist George Perez to agree to ink Swan’s pencils. Perez was almost as popular as Byrne, and his linework helped to give Swan’s final story a bit more of a modern flavor, to make it more instantly appealing to the readers of 1986 that found Swan’s work a bit old-fashioned.

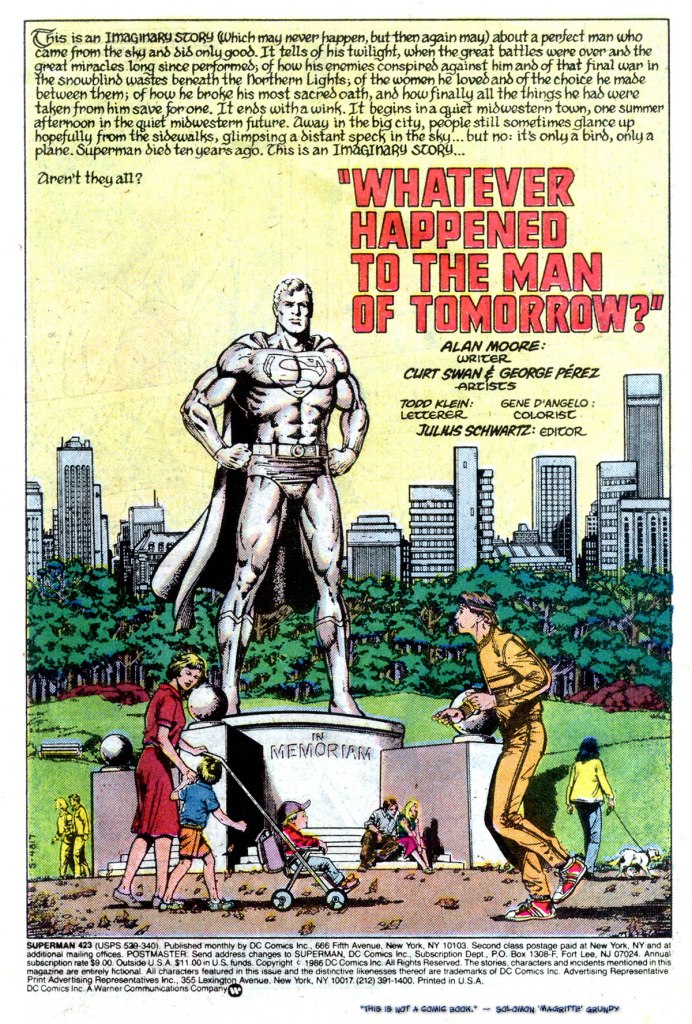

It has to be said that Alan Moore was more an aficionado of the Superman stories produced by Schwartz’s editorial predecessor Mort Weisinger in the 1950s and 1960s than the fare that Schwartz had overseen since that time. Those were the stories that resonated with Moore the most for their fantastic flights of imagination (despite their very childish approach to narrative and characterization.) So he channeled his love of that period into crafting a tale that would make use of all of Weisinger’s canon and treat it with reverence rather than ridicule. In a tip-of-the-hat to one of Mort’s innovations, Moore opened the story declaring it to be an “Imaginary Story” and following up with the clever declaration, “Aren’t they all?”

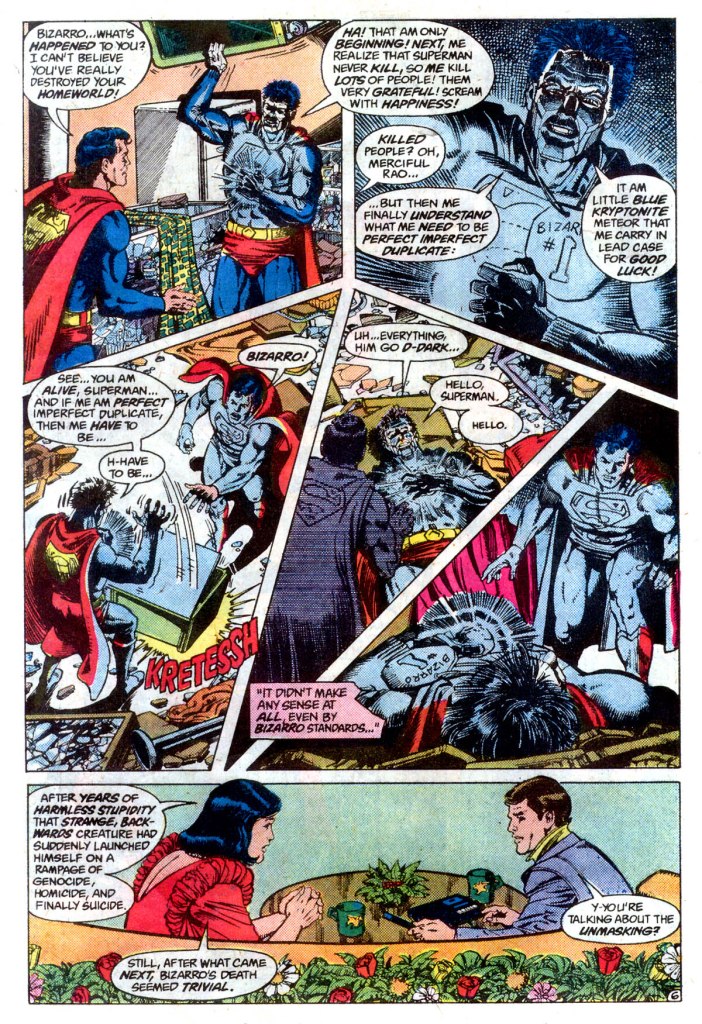

The tale opens in the future, at a point where it’s been a decade since the Man of Steel was last seen in Metropolis and he’s believed to be dead. Tim Crane, a reporter for the Daily Planet, is doing a feature piece on the hero and his final days, and so he’s come to the home of the former Lois Lane, now Lois Elliot, to interview her about the events of ten years previous when Superman fought his final battle. As Lois recounts the tale, we get to witness the events firsthand. After a period of relative peace in which Brainiac had been destroyed, the Parasite and Terra-Man had annihilated one another and Luthor had vanished, events kicked off when Bizarro went on a homicidal and uncharacteristic rampage across Metropolis. Confronted by Superman, Bizarro explains his backwards logic: Superman saves people, so as an imperfect duplicate, he should kill people. Superman came from a doomed planet, so Bizarro has intentionally destroyed the Bizarro World and all of its inhabitants. And Superman is alive, so Bizarro exposes himself to a fatal dose of Blue Kryptonite as a form of suicide. Superman is disquieted by these events, as were the readers. Moore cleverly plays by the established rules of the character and twists them just enough to produce an unexpected and horrific effect.

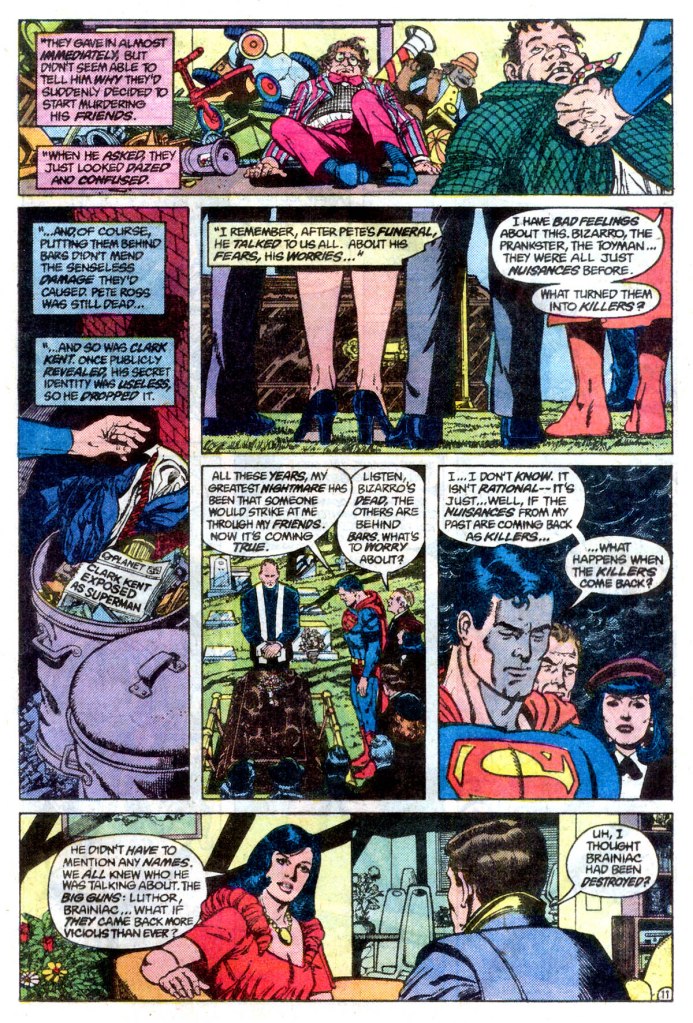

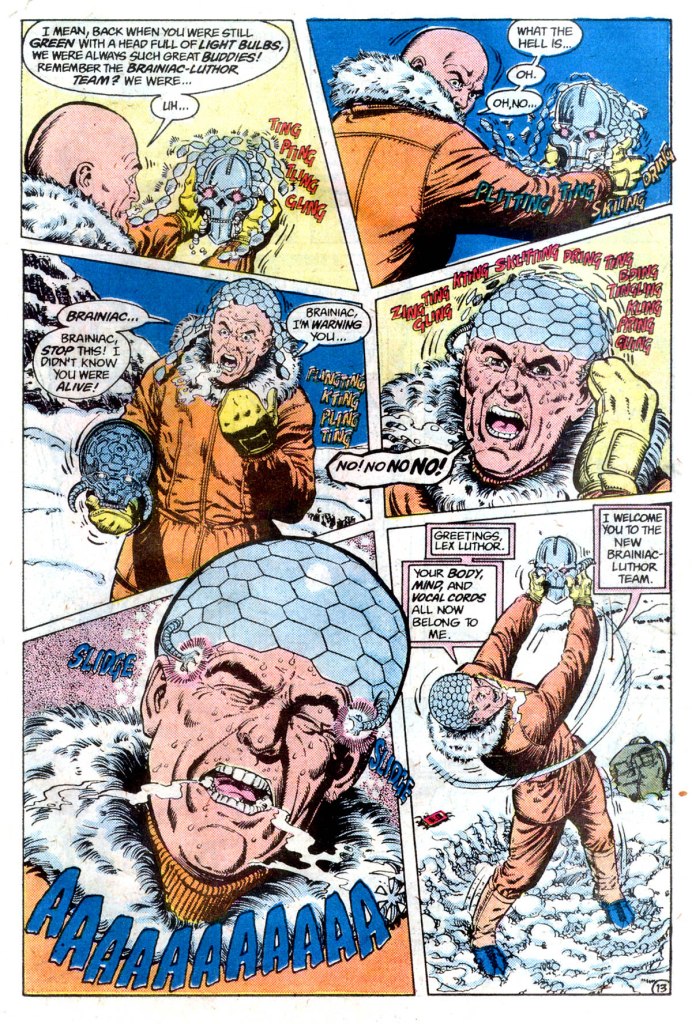

Lois explains that after that, the Toyman and the Prankster joined forces. They somehow learned that Pete Ross knew Superman’s true identity and tortured it out of him, then exposed Clark Kent as Superman on live television. When questioned, the pair couldn’t explain how or why they had done so, but the Man of Steel’s civilian life was now gone. Elsewhere, Luthor resurfaced, tracking down the remains of the destroyed Brainiac with the intent of making use of its advanced technology. But Brainiac, it turns out, wasn’t so demised as everyone thought, and the cybernetic creature hijacks Luthor’s body, turning him into a meat puppet it can manipulate to get its revenge on Superman for destroying it. On top of this, the Daily Planet building is destroyed by an army of Metallo cyborgs. Realizing that these attacks on himself and his friends are calculated, Superman relocates his cast to his impregnable Fortress of Solitude for their own safety.

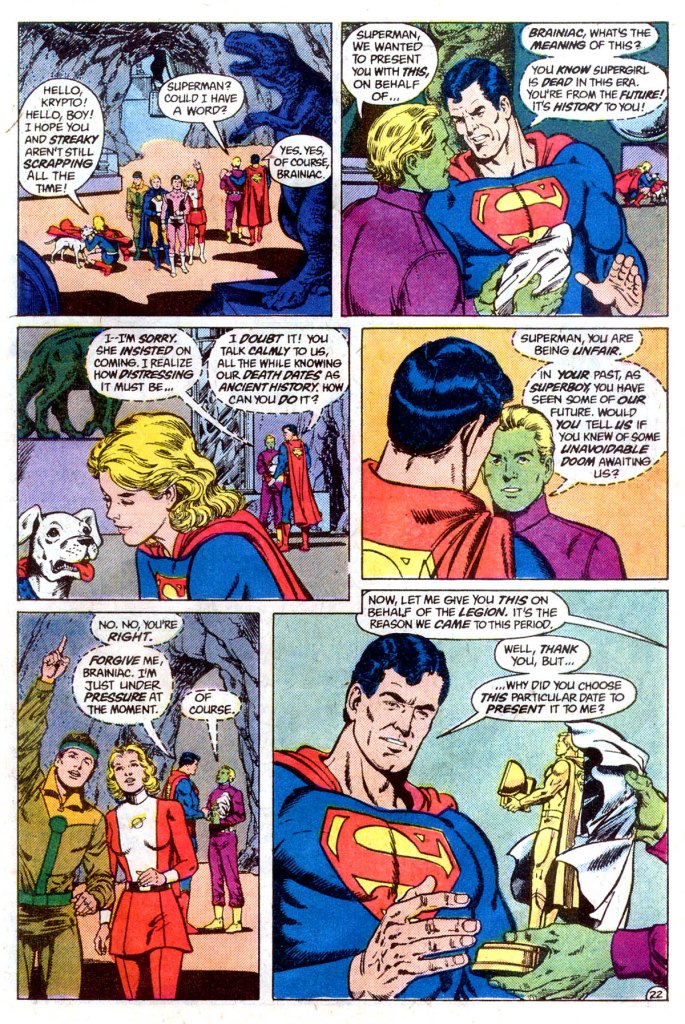

As the Luthor/Brainiac hybrid inexorably draws closer, Superman prowls the halls of the Fortress with Krypto, feeling a sense of impending dread. This feeling is only accentuated by the arrival of his future friends the Legion of Super Heroes. They’ve come to present him with an award but are elusive about why they’ve chosen this particular moment to do so. What’s more, the young Legionnaires have brought Supergirl with them. The modern day Supergirl had tragically perished during the Crisis on Infinite Earths, so Superman is horrified to see her young and vital again. Moore cleverly refutes Superman’s argument with the Legion about the callousness of them knowing the death-dates of himself and Supergirl by framing the shot around Invisible Kid, whom Superman knows will himself perish due to adventures the Man of Steel experienced when he was a boy. The Legion are clearly here to pay their last respects, and after they depart, Superman breaks down in tears.

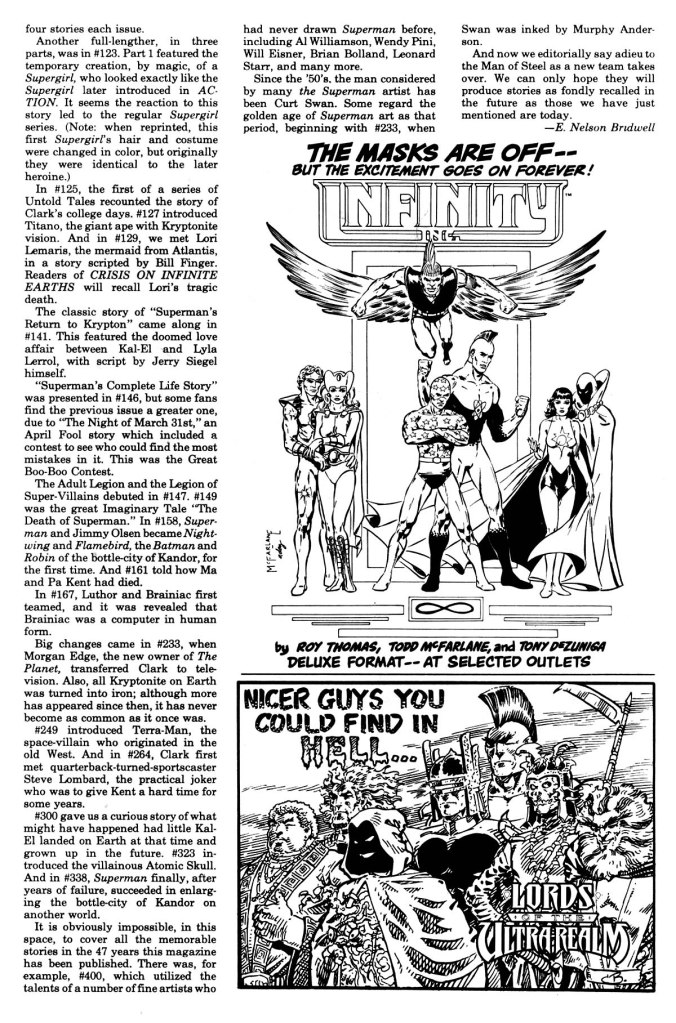

The story would be concluded in ACTION COMICS #583, Schwartz’s final issue editing that series as well, in a chapter that’s just as good as this one, just as affecting. As an added bonus, Assistant Editor E. Nelson Bridwell, who possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of Superman’s history, filled the inside front and back cover with a retrospective of the key events that had transpired in the series since it first began in 1939. I can recall the two-week wait for the second chapter of this story feeling incredibly long, so perfectly did this tale hit its mark and rekindle my love of Superman and all of the crazy, implausible elements of his universe. Just as Moore had previously done with MARVELMAN, by looking at these ideas from a different angle, the writer imbued them with pathos and found interesting wrinkles to play out with them. Seriously, Krypto’s demise in the second half is a genuine tear-jerker and perhaps the most that anybody cared about that dopey pooch until James Gunn’s recent film. This two-part story also threw down the gauntlet to John Byrne at least as far as the old guard fandom was concerned. it proved, they insisted, that no reinvention of the character was needed, only superior writing. While they (we) may have had a point, Bryne’s take on Superman would become incredibly popular and make the character a top seller once more.

I teared up twice reading this, remembering the story well because it may be one of the most re-read Superman stories for me. Just remembering Krypto’s last stand (as well as two others who don’t make it the last page) was the biggest trigger. I didn’t follow Moore’s Swamp Thing because it was more true horror than I liked and my feelings for Watchmen are mixed because how other writers took the wrong elements to copy when it was a hit but these last two Bronze Age Superman stories will always be a favorite. Moore really did get and respect Superman and it shows.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This wasn’t a perfect game for me — I forget offhand whether it was in part 1 or part 2, but it bugged me that Superman was facing the villains doing things that he would have handled easily in the Weisinger days, and he just gave up without much effort here. This was also my complaint about the DC PRESENTS Moore wrote, but at least there it was drawn by Rick Veitch — seeing it drawn by Curt Swan made it feel much more like a Weisinger story and brought into relief how different Superman’s reactions here were than they would have been in the 1960s. In fairness, I understood that Moore had two issues to wrap it all up, and so things had to happen fast, but it still bugged me. What, Superman, your shirt’s been torn open revealing that you’re wearing your costume under your Clark Kent clothes? So you go, “Yeah, okay, it’s true?” How many times have you been in the same situation before and deflected things easily?

It also bugged me that the whole revelation with Mxyzptlk is lifted from Robert Mayer’s SUPERFOLKS, including almost direct dialogue swipes, and I’d already noticed Moore swiping other authors’ work before. So while I recognize it as a powerful and elegiac ending for the Earth-One Superman, it wasn’t an unalloyed triumph for me. It was very well written and it looked great, but I was too conscious of flaws.

[Ironically, what I thought made Moore’s other Superman story work so well — Superman’s indomitable spirit, overcoming even the Black Mercy’s dream-effect — was why I had problems with the other two, where he seemed to give up too easily.]

But, well, crab, crab, crab…

LikeLiked by 2 people

In the Justice League Unlimited cartoon episode “For The Man Who Has Everything” it was Batman yelling at him that got him to start questioning the perfect world the Black Mercy helped him create in his mind. I never saw the Alan Moore version. Just the cartoon and the CW Supergirl version ( which had her adopted sister Alex Danvers projected into her mind to help her — “For The Girl Who Has Everything” ).

LikeLike

This one has always fallen flat for me, even though I can’t specify what it is that doesn’t work (I hadn’t read Superfolks at the time). Perhaps what you’re talking about is part of it.

For me the LSH story where pocket-univers Superboy dies saving his friends is the best goodbye to the Earth-One Kal-El.

LikeLike

Yeah, the borrowings from Superfolks bugged me a bit as did Moore’s many other cut-and-pastes that I learned about later (e.g. E.T. in Skizz, The Master and the Margarita cop in an early issue of Swamp Thing run, etc.) That said, his borrowing from Superfolks actually worked pretty well, adding to the genuine emotional resonance of the story in way that I certainly didn’t get from Superfolks, although I enjoyed the novel well enough.

Re: the Clark Kent revelation, I have long assumed that Moore never liked the whole Clark Kent thing and wanted to dispense with it ASAP. Clark doesn’t appear in “For the Man Who Has Everything” and Clark’s appearance in the DCCP Swamp Thing team up is brief, during a depowered phase.

LikeLike

That is insightful.

What I think Moore was trying to capture was a situation where you have a cascading collapse. Enough is going wrong, that Superman no longer has the resources to solve one problem and deal with the next.

In the end he can only go on (continue living) by stopping (being Superman).

I think his idea is that old dictum of Orson Welles, “If you want a happy ending, that depends, of course, on where you stop your story.” However, you make me wonder if he sold it, in the end.

LikeLike

I agree that that’s what Moore was trying to do, and it clearly worked for many, many readers. I was even aware, at the time, that my objections requires Superman doing the story of “silly” plot behavior that he really didn’t do any more. But to my mind, Moore seemed very much to be writing the Weisinger Superman, and this was made even stronger by Swan drawing the story in a way that felt more like the Weisinger era than the Schwartz era, something I assume was a product of the way Moore wrote the script.

And the Weisinger Superman didn’t get overloaded, at least not by that kind of thing.

So while I might well have bought it if it was drawn differently, or paced differently, it didn’t ring true for me as it was.

But I was clearly in the minority there.

LikeLike

I wonder if Alan Moore’s Brainiac-Luthor merger was the inspiration for the WB’s Justice League Unlimited episodes 24 & 25 “Panic in the Sky” & “Divided We Fall” – July 09 & 16,2005 ( Years earlier Brainiac inserted a microscopic copy of himself into Luthor’s body when he forced Luthor to build him a new body inside LexCorp — “Ghost in the Machine” — Superman: The Animated Series — dcau.fandom.com ) and later Luthor convinces Brainiac to merge with him because he can show Brainiac a higher purpose by providing him a trait he lacks, imagination ( I just noticed that reminded me of Commander Willard Decker & V’ger in Star Trek: The Motion Picture –1979 ).

LikeLike

When I saw or read about the Sub-Mariner’s Timely Comics foe the Iron Brain [ Sub-Mariner Comics#30 ( February 1949 ) 1st story — criminal genius, given mechanical brain after hanging, caused heat wave with Earth-moving machine, created monstrous Aquasaurus Rex. Namor crushed his skull, but his mind was downloaded into that mechanical brain so perhaps it can upload to another nearby mechanical brain ], I thought of him as a Brainiac-Luthor amalgamation ( The Iron Brain, Doctor Feerce [ Marvel Mystery Comics#79 ( December 1946 ) over 1000 year old Greek scientist ( 970 AD )– lab accident made him immortal ( he was starting to age in this story, but perhaps the electric chair execution acted on the chemicals still in his body and restored his immortality ). Also he is very short — marvel.fandom.com ] and the Shark-Man ( Nazi mutate — marvunapp.com ) [ Kid Komics#4 ( Spring 1944 ) Sub-Mariner story – ( He looks like flabby Abomination, but I would give Tiger Shark’s man-shark form ) are the Golden Age Namor foes I wish were active in modern Marvel among his current foes )– I know this is all about Superman but I got carried away.

LikeLike

ALMOST FORGOT THIS PART ( Tom comment on Alan Moore ): .. so he channeled his love of that period into crafting a tale that WOULD MAKE USE OF ALL WEISINGER’S CANON and TREAT IT WITH REVERENCE RATHER THAN RIDICULE. The writer of Marvel Adventures Super Heroes#21 ( May 2010 ) might not have been channeling any love for Gary Gaunt [ Mystic Comics#9 ( May 1942 ) ] but he TREATED HIS TIMELY COMICS ORIGIN in that UNIVERSE WITH REVERENCE RATHER THAN RIDICULE or IGNORING IT by explaining the experiments with rabbits had nothing to do with trying to create attack rabbits but studying aggression ( Which I suggested could mean he was working on a chemical cure or stabilizer to the Super-Soldier Serum not stabilized by Vita Rays ) — unlike the “writer” of The Twelve wo ignore the Fiery Mask’s origin and gave him the Silver Age Green Lantern’s instead ( or the Torpedo ) Brock Jones ) or Nova’s or Power Pack kids ) or the various writers of the 2005 Marvel Monsters series of books that didn’t treat the monsters with the same seriousness those characters were in the 1960s ( Those stories might be simple, but they were written as camp ). X-Men#111 ( June 1978 ) where Beast ( Henry McCoy ) used Professor X’s training to resist Mesmero’s hypnosis, just like Dr. Jack Castle ( before he gained his Fiery Mask powers ) resisted the mind-control/hypnosis ray in his Timely Comics origin.

LikeLike

I like Alan Moore’s work. I like George Perez’s work. But this story never made much of an impact on me. A lot of it probably has to do with the fact that I never cared for the Silver and Bronze Age version of the character, so bringing all of that stuff to a close was emotionally inconsequential to me. Also, I never, ever got the appeal of Curt Swan’s artwork. I’d describe it as competent but bland. And as much as I like Perez’s artwork, I never cared much for his inking (it always felt too overworked (with the exception of that Sirens book he did late in his career where I felt he finally became a solid inker)).

I get that a lot of people really like this story, and I’m glad they do. But at the time (I was 13 in 1986), I couldn’t wait for the Byrne run to begin. And, to this day, that two-year run is still probably my favorite comic book iteration of the character.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Re: Moore’s favoring Weisinger’s Superman over Schwartz’s, to be fair, Moore did provide at least one genuine Julie moment when Superman magnetized the Daily Planet symbol to deal with and had Lois explain the process in a very Schwartzian way.

LikeLike

*to deal with the multiple Metallo menace.

LikeLike

One nice understated detail, in the last page with the Legion: Brainiac 5 asks Superman if he would warn them about some future doom, and the very next panel has Invisible Kid in the foreground, a Legionnaire who died in the line of duty.

(His death was one of my very first Legion issues I ever bought, in fact.)

LikeLike