In 1982, I was a huge fan of Pacific Comics, and really all of the new companies that had begun to spring up in the developing Direct Sales marketplace. These new companies and their assorted offerings excited me with the possibilities. I truly felt that I might be on the ground floor of some future Marvel, having come to that outfit far too late to have been there at its formative days. I’d imagine that readers of a later generation felt the same way about the initial Image books, to say nothing of Valiant and Dark Horse and all of the other new companies of the 1990s. But something new and different was definitely what I was intrigued by at this time, and so Pacific Comics and its growing output was like catnip to me.

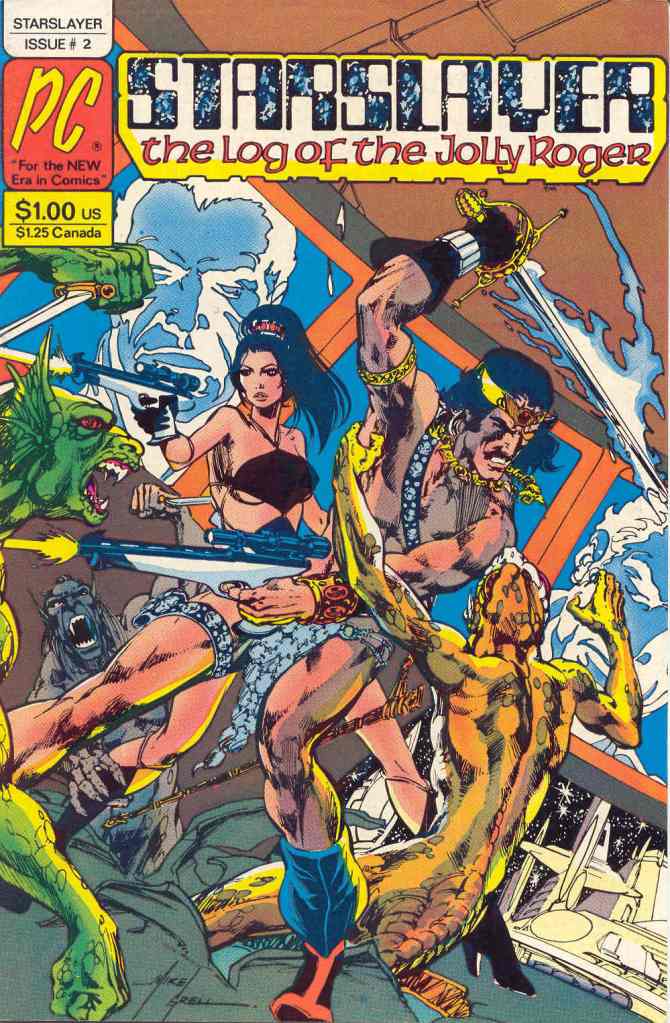

So I bought STARSLAYER right from the first issue, though this is #2 that we’re going to be looking at for relatively obvious reasons. And the ironic thing about it is that I wasn’t especially a fan of its creator, Mike Grell. I knew Grell from is assorted DC work, most notably on LEGION OF SUPER-HEROES. I was also familiar with his popular and long-running series WARLORD. But I never so much as sampled WARLORD–it seemed like it was a barbarian comic book and what I wanted from my comics was always super heroes, so I just didn’t have an interest. So picking up STARSLAYER #2 was driven by a combination of really liking the idea of a new third company and wanting to be there at the ground floor (and not wanting to see early copies listing for exorbitant prices in a couple of years and remembering when I could have gotten them for cover price.)

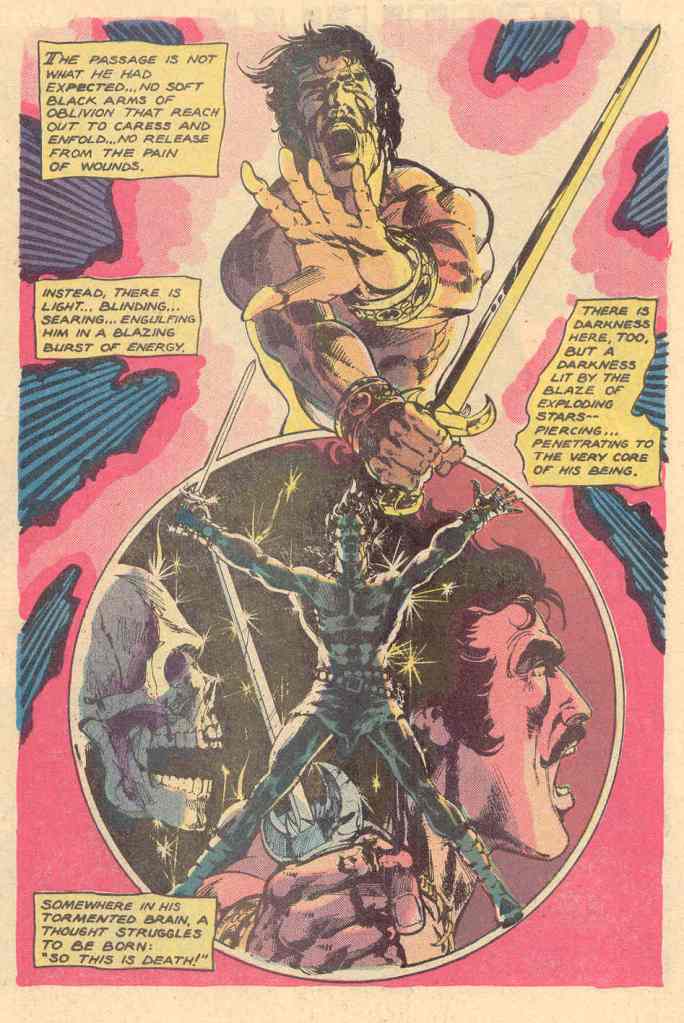

The premise of STARSLAYER was an inversion of Grell’s earlier series WARLORD: in that title, a modern day soldier finds himself in a strange sword-and-sorcery realm secreted at the center of the Earth and becomes a heroic fighter. In STARSLAYER, the lead character, Torin Mac Quillon, is pulled from the distant past at the moment of his death into the far future, a world that needs a heroic champion of its own of the sort that centuries of civilization have bred out of the men of that era. Torin awakens in this issue in this future time and is schooled by Tamara, the woman who has drawn him here, as to what the situation is in this tomorrow time and what they need him to do.

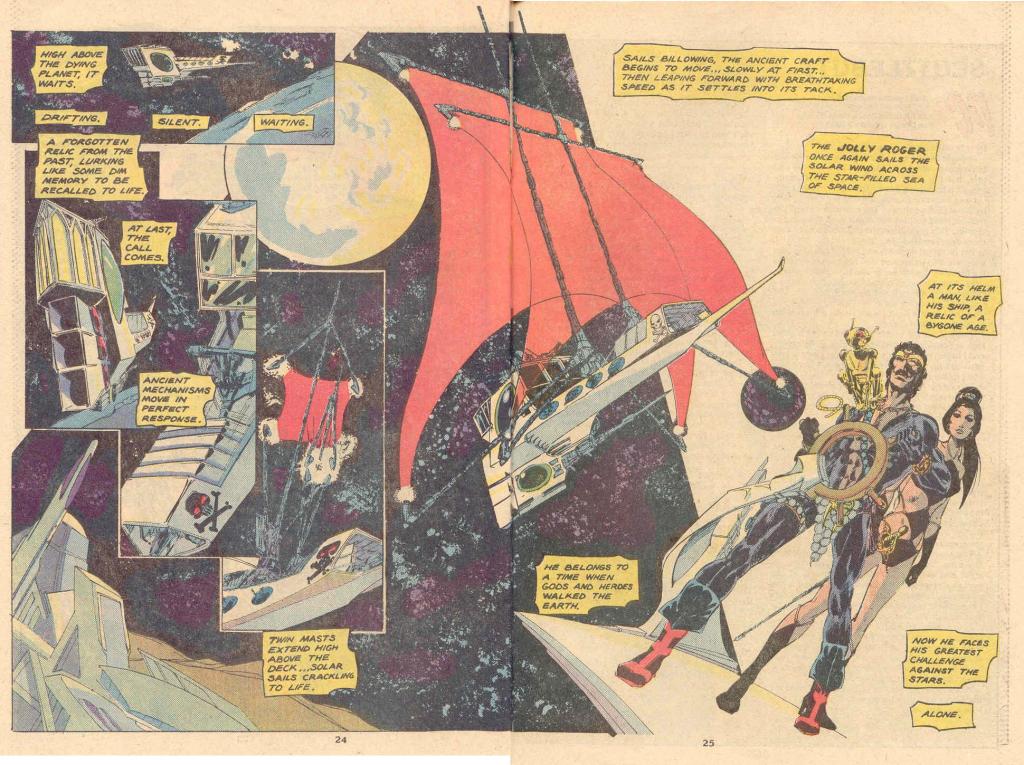

As an aid to his understanding, Tamara provides Torin with a high-tech headband that not only restores the sight of his lost eye, but which also pairs him up symbiotically with SAM, a Simbionic Android Mindlink–essentially a robotic monkey–which can feed him information and analysis about the world he now finds himself in. He’s also kitted out with futuristic weapons, a sword and a firearm, as well as a full costume–only some of which he prefers to wear initially. The civilization of the future needs Torin to seek out and reunite a series of amulets, each of which was given to the leader of the colonization efforts across the solar system. Together, the amulets can unlock a power source great enough to defend the Earth from the transmogrified settlers of the outer planets, who have turned against the Earth government. It’s a relatively simple quest plot: gather up the macguffins and save the day.

It’s also pirate adventure in space, something that I could wrap my head around a lot more easily, somehow, than barbarians at the Earth’s core. The lettering in this story was often shaky and the coloring was trying for a more fully-realized effect than the usual four-color separations that were then available. But the kinks hadn’t been worked out yet, and so the presentation is a big, uh, sloppy-looking. I had no idea at the time that STARSLAYER had been developed as a property for DC but that it was spiked by the DC Implosion and that therefore Grell took it to Pacific where he could retain ownership and rights to it. It wasn’t a polished presentation at Pacific, but there was something about it that I liked nonetheless. so not a big favorite or anything, but at least a title that I’d continue to follow. And one of the reasons for continuing to pay attention to STARSLAYER premiered on the following page.

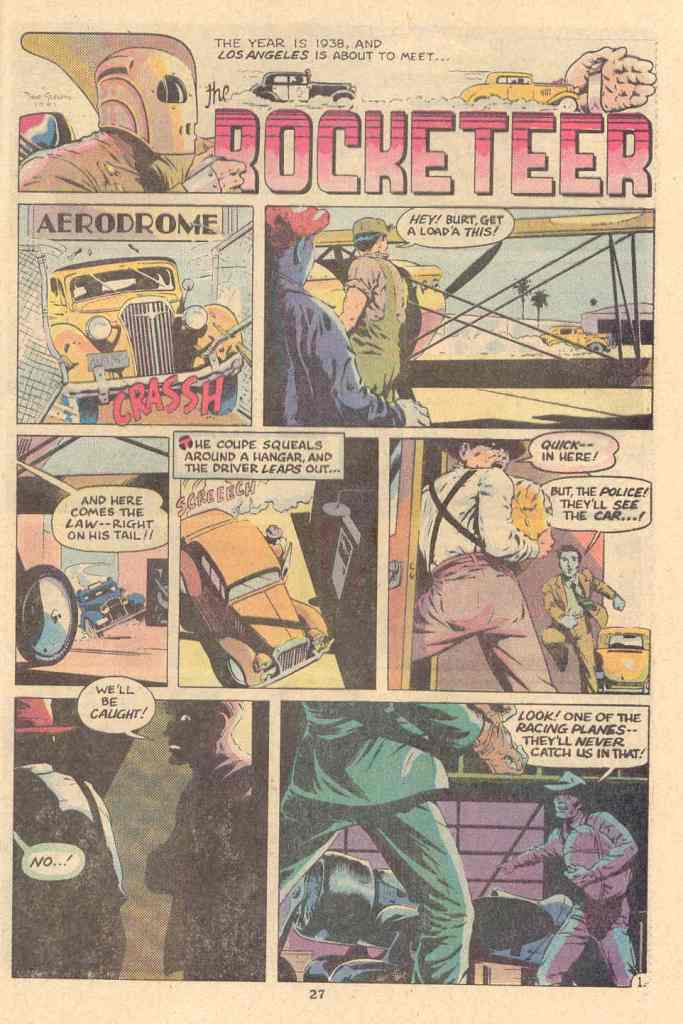

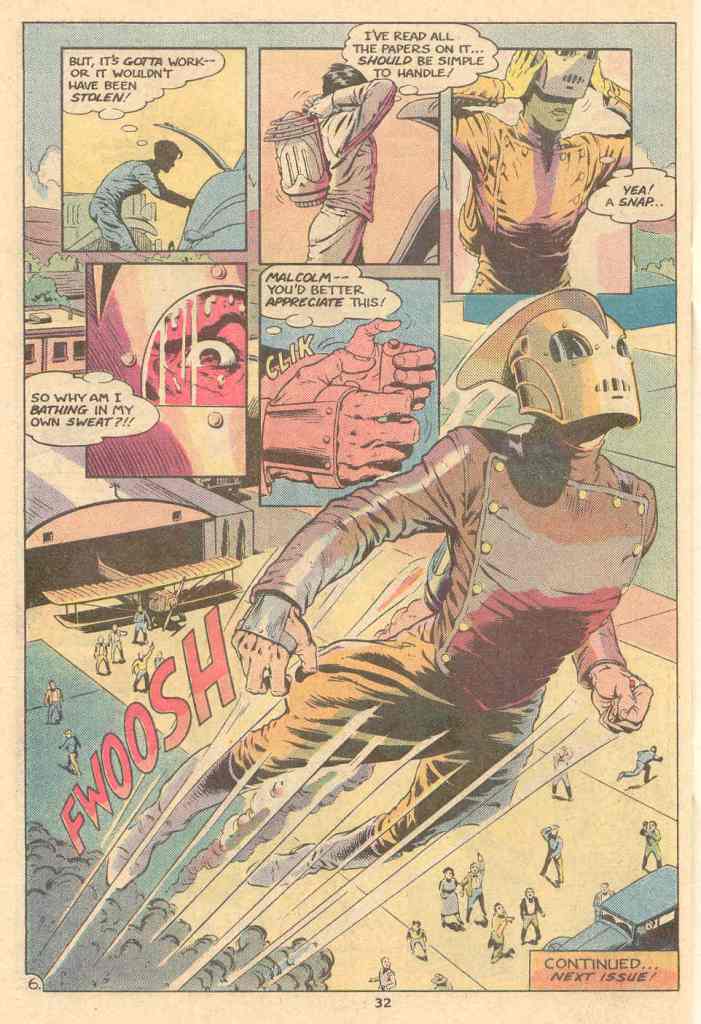

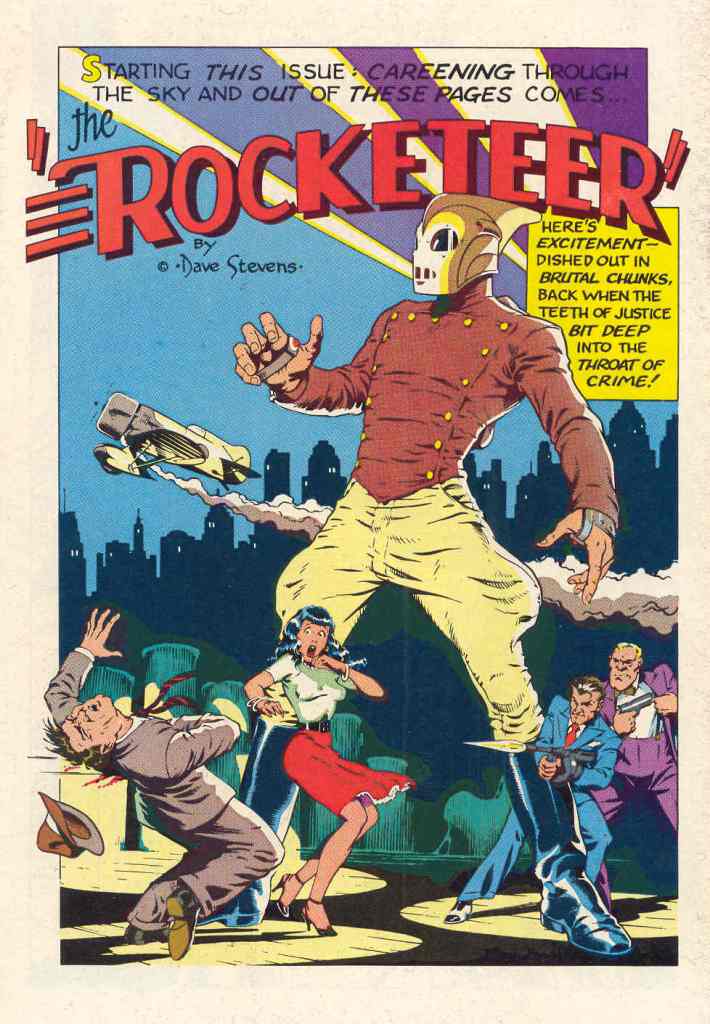

I had no idea who Dave Stevens was. I doubt than many readers did, apart from maybe a few who’d met him at the San Diego Comic Con over the years or knew him from his work in film. But his back-up series The Rocketeer caught people’s attention immediately with this initial offering. As I understand things, with Grell unable or unwilling to fill up the entirety of this issue and future ones, Pacific needed filler, and so they turned to Stevens to craft something, anything, for them to fill the space. Dave took inspiration from a bunch of the things he loved, pulp adventure and movie serials and the verve of the 1930s and came up with the story of Cliff Secord, a hard-luck aviator who stumbles into possession of an advanced rocket pack which enables him to fly without a plane.

Much of what would make the strip noteworthy–including the first appearance of Betty page within its pages–wouldn’t happen for another issue or two. But even here, limited to a mere six pages in which he races through his character’s origin in almost shorthand, Stevens expert draftsmanship and talent for caricature and cartooning as well as dramatics comes through meaningfully. The Rocketeer was instantly a strip readers were paying attention to. The Rocketeer helmet is possibly the greatest full-face character design since Steve Ditko’s Spider-Man, and gave the character an instant recognition and appeal.

It’s great stuff, and has been much-reprinted over the years, even given that Stevens only managed to produce two extended stories for the character (with a bunch of help from others–Stevens was meticulous with his artwork, which made him slow.) Moreso than the interior pages, this back cover image really summed up the flavor of the series and hinted towards the potential of it as a serial. I know that I was instantly hooked by it, and only got more so as further installments unfolded. It was finding strips such as this one that was the whole reason I was so enamored of all of the new companies that were springing up–there was a lot of irredeemable crap as well, and material that was no better or really different than the mainstream. But every once in a while, you’d stumble across a gem such as The Rocketeer.

Good article. I liked the coloring attempts in this issue. Some rough spots, but the intent was appreciated. Strong drawing by Grell. And of course a landmark story by Dave Stevens.

Tom wrote: “I’d imagine that readers of a later generation felt the same way about the initial Image books, to say nothing of Valiant and Dark Horse and all of the other new companies of the 1990s.”

Apologies, but Dark Horse started publishing comics in 1986. I was buying them right away, with DHP, and “The MarK” soon after.

From Wikipedia:

“Dark Horse was founded in 1986 by Mike Richardson with Dark Horse Presents No. 1 and featured the first appearance of Paul Chadwick‘s Concrete and Chris Warner‘s Black Cross, selling approximately 50,000 copies, which was far better than predictions.[8][11] The series has become a platform for new creators to highlight their works.[11] The success of Dark Horse Comics can be attributed to a change in comic book marketing that occurred in the 1980s when comics began to be sold in comic specific stores.”

“After his success, Richardson began buying the rights to several titles including: Godzilla in 1987, Aliens, Predator in 1989, and Star Wars in 1991 (owned by Marvel prior to the Dark Horse Comics acquisition). Dark Horse evolved further and began producing toys in 1991. In 1992, Richardson formed Dark Horse Entertainment, the company’s critically acclaimed film and television division.”

“With the release of the first Aliens comic in 1988 and Predator in 1988, Dark Horse Comics’ popular characters appeared in their own line of work as well as Dark Horse Presents and Tarzan and numerous crossovers that included Superman and Batman of DC Comics, and WildC.A.T.s.”

LikeLike

That shaky lettering in STARSLAYER is apparently by Grell himself.

And yeah, the Rocketeer was an absolute bombshell of a debut. I wasn’t even reading STARSLAYER — I wasn’t interested in space pirates much — but I heard so much about the Rocketeer I had to track a copy down.

LikeLike

I started with issue 4 and loved it so much that I immediately bought the first three issues as back issues the next time I went to the comics shop. I subscribed to STARSLAYER when it went to First Comics, and I kept reading all the way through to the bitter end (#34).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve seen the recolored Rocketeer for so long that the original coloring is jarring. I know that there are a lot of comics fundamentalists out there who believe that original coloring should always be preserved when comics are reprinted, but the recolored Rocketeer is just better.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have no idea why I’ve never read any Rocketeer. I reason I skipped this is a lifelong dislike for Grell’s art. I was stuck with Warlord (completism) and Legion (One of my two favorite teams) but no way was I going to touch anything else with his art in it unless it was a series I was already committed to. I did notice the very small loincloth suggests something else was very small for this hero as with Travis Morgan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s strange that I didn’t glom onto Starslayer at the time; I was a big fan of Grell’s Legion and Warlord, and this seemed to have elements of both. I think perhaps I dismissed it as Grell running out of ideas and regurgitating the same kind of stuff he’d already done. To this day, I still haven’t read it, so I couldn’t say if that was actually the case.

Of course, that meant I was late to the Rocketeer party as well, although I did manage to grab the collected edition when it came out. As Tom and Kurt said above, it was mind-blowing that this unheard-of guy suddenly turned up doing such polished and confident work, like he’d sprung forth from the forehead of Zeus or something.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Rocketeer film ( 1991 ) was the first time I saw the character and had no knowledge he began in comic books. I rewatched it a couple of years ago and it still held up to me. I’ve seen the Starslayer series in back issue box years ago, but it was a friend who introduced me to Mike Grell’s Jon Sable Freelance ( to read and I watched the Sable short-lived TV series. Didn’t until today know it introduced Rene Russo to audiences )

LikeLiked by 2 people

The Rocketeer was my inspiration for wanting Breeze Barton ( Kurt Barton ) who has a jet pack [ Daring Mystery Comics#3 ( February 1940 ), 4 ( May 1940 ) & 5 ( June 1940 ) ] to be active in 1945 and 1990s at the same time by borrowing from Star Trek: The Next Generation episode Second Chances ( 2 Will Rikers created a a unique energy field around a planet and a second unnecessary transporter beam — one rescued and one stranded on the planet ) and revealing that changes made to escape the one way portal to the dimension that the City of the Mirage/Miracle City created 2 of them ( Breeze Barton & Ann Barclay ) that ended up in different time periods ( 1945 and 1995 ). A version of him ( made references to early 21st century pop culture he shouldn’t have knowledge of ) appeared in Marvel Zombies Destroy!#1 ( July 2012 ) as a member of the Ducky Dozen ( marvunapp.com ).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I still say the rocketeer and the phantom are two of the most faithful-feeling comic book/strip adaptations, although I’d prob say Road to Perdition or A History of Violemce are the best films adapted from comics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

KING OF THE ROCKET MEN ( 1949 12 chapter movie serial from Republic Pictures. Shots of Jeff King as Rocket Man taking off, flying and landing were reused in Radar Men from the Moon ( 1952 ), Zombies of the Stratosphere ( 1952 with a young Leonard Nimoy as an alien ) and Commando Cody: Sky Marshal of the Universe ( 1953 ) all by Republic ) is probably the inspiration for The Rocketeer. Clearly the inspiration for Star Trek: Voyager’s Tom Paris’ Captain Proton’s jetpack and outfit ( Season 5 episode “Night” — can’t remember if he wore a helmet too ) or as Reddit says Commando Cody.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For me, Warlord and Starslayer have more in common than Grell: I only bought either title for the back ups, Warlord for Arion, and Starslayer for Rocketeer and Grimjack. I never bothered with Sable at all, despite my singular status as a First Comics zombie.

LikeLike

You weren’t the only First Comics zombie …

LikeLiked by 1 person

But I never see at the meetings! 😉

LikeLike

There was a period where I stopped reading comics around maybe 1977. And then I picked up a few years later when I discovered a big cache of Warlords at the local used book store. I bought those, started buying Warlord as it came out and then started buying other comics. Mostly, if not all, DCs.

One of my friends showed me the ad for Starslayer knowing my love of Mike Grell. I got a subscription (small town, no comics shops, might not have been able to drive when the series started) and really loved the first issue. The series got less fun when it went into space and even less fun at First with other creators.

After years and years of Vince Colletta inking Mike Grell it was sure nice to see him ink himself. I still like the artwork in this series.

And, yeah, the Rocketeer was awesome. More awesome than the main book. Rewatched the movie the other day after reading this. The movie is perfectly fine, but not a labor of love like then comic was.

LikeLiked by 1 person