Jim Shooter is one of the most undeniably important figures in the history of comics. A child prodigy, he first broke into the business when he was only 13 years old, submitting stories to DC editor Mort Weisinger for the Legion of Super Heroes feature in ADVENTURE COMICS. Not realizing quite how young Shooter was, Weisinger bought a number of his stories before learning the truth, and kept him on board even after the fact. Eventually, Jim became the Editor in Chief of Marvel Comics, which was in a bit of editorial disarray. He corralled the chaos, instituting the editorial system that is still used today in place of the outdated arrangement where a single editor was responsible for the content throughout the entire line.

Shooter had been drilled on the craft of making comic books by his mentor Weisinger, and he in turn drilled those same lessons into a generation of Marvel creators. He had a good sense of story and a lot of confidence in his own abilities. Unfortunately, he was often a mercurial boss who created a lot of friction among Marvel’s freelance and editorial staff as time went on. Some of that was unavoidable; as the EIC, Jim was ultimately the guy who often had to say no. But it wasn’t all unavoidable. Eventually, matters reached a head and Shooter was ousted by Marvel.

Picking himself back up, Shooter pulled together a group of investors and like-minded partners to attempt to buy Marvel Comics outright. This bid failed, but in its aftermath, having raised the cash necessary to fund a start-up company, the group did exactly that. Shooter was put in charge of Valiant, a new comic book company based around a number of classic super-heroic characters licensed from Gold Key.

Valiant was an unlikely success story, but it became one steadily over time. Shooter kept a tight control over story content, even as he was often forced to rely on the work of both fresh young newcomers and elder talent who were largely considered past their prime. Despite this, his approach to creating characters and blocking out a universe really struck paydirt with a certain segment of the audience, and the promotional gimmicks that the company had rolled out, including rare gold-logo variants of their hottest releases, fueled speculation in their fortunes. Everything was rolling along very well.

It was at this point, however, that Shooter was ousted from Valiant as well. Accounts differ as to exactly what transpired and what the cause was, but matters reached a head and Shooter was cast to the curb. Undaunted, he once again picked himself up, arranged for some financing, and began yet another comic book company: Defiant.

From what I can tell, Defiant was operating on an even more haphazard basis that Valiant had at its start-up–helped not at all by a nuisance lawsuit from Marvel that claimed that Defiant’s launch title, PLASM, infringed on the trademark held by Marvel UK for PLASMER. The matter seems frivolous to me, but fighting the lawsuit burned through the lion’s share of the capital that Defiant had to work with. Ultimately, the company lasted for about two years, during which time the most issues any of their series released was 13.

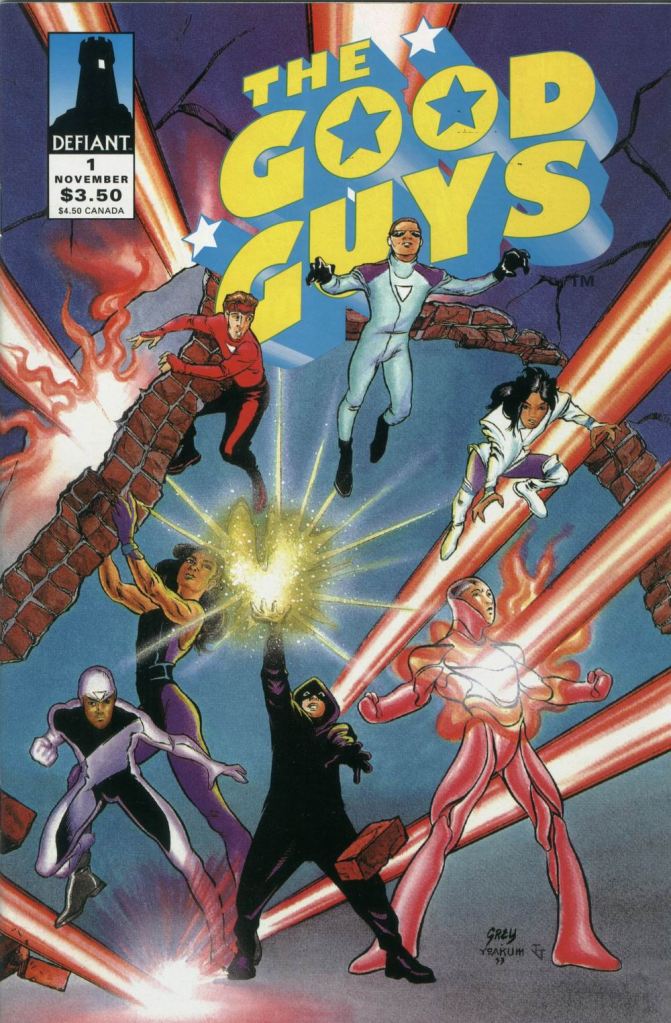

Which brings us around to THE GOOD GUYS. This was the third or fourth Defiant series to be released, and the one that seemed to have the most in common with other previous comics. It featured a team of young characters who gain superhuman powers, a winning formula ever since the launch of the Uncanny X-Men. It also contained some of the flavor of Shooter’s earlier Valiant creation HARBINGER, which was similarly about a group of young people whose newfound powers thrust them into a larger global conflict. It seemed like a strong contender to become a hit.

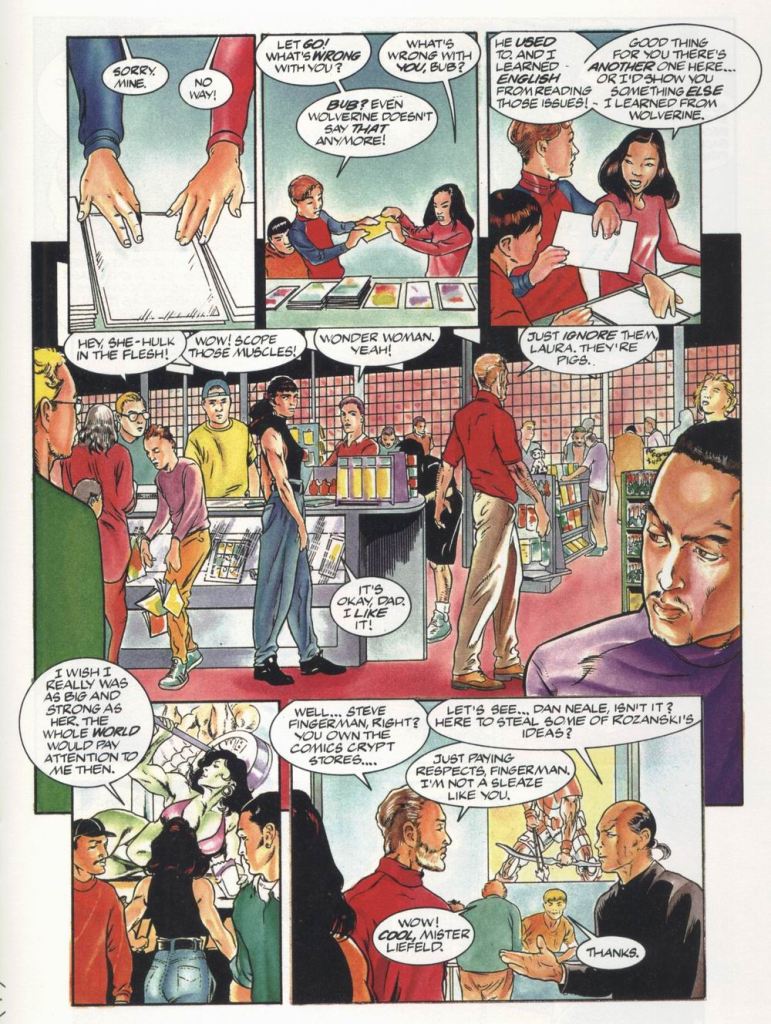

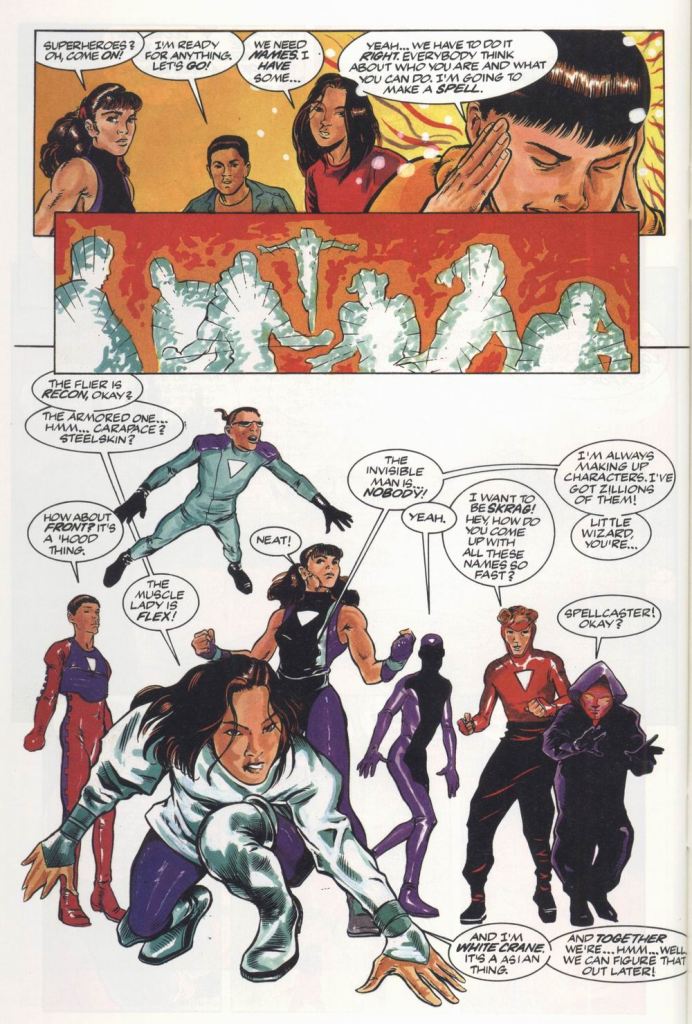

There was an additional promotional aspect to THE GOOD GUYS. Defiant held a contest among the readership, casting a bunch of real-world fans as the lead characters. In practice, I’m not certain how this all worked on a practical level–it seems as though the basics of the characters had already been worked out, with the fans only contributing their names and possibly a bit of their likenesses to them. The telltale sign is the fact that the real-world counterparts of brothers Skrag and Spellcaster aren’t related at all. In any event, this was a fun promotional effort and helped to create some buzz around the launch of the title.

Now, not to put too fine a point on it, but while there’s a good comic book buried within THE GOOD GUYS somewhere, it never comes together, not in its launch issue and not for the duration of the remainder of its run. So it’s a good object lesson that even the most accomplished creators can put out a turkey from time to time. There are a whole mess of things wrong with this series, and having familiarized myself with the run, I’d like to talk about them a little bit.

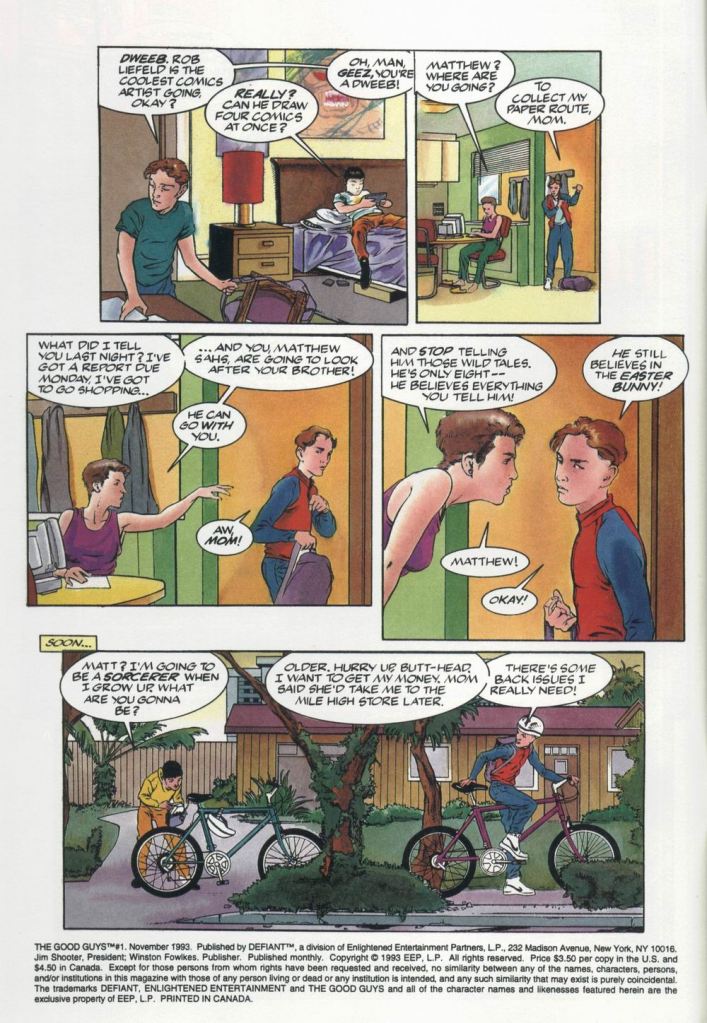

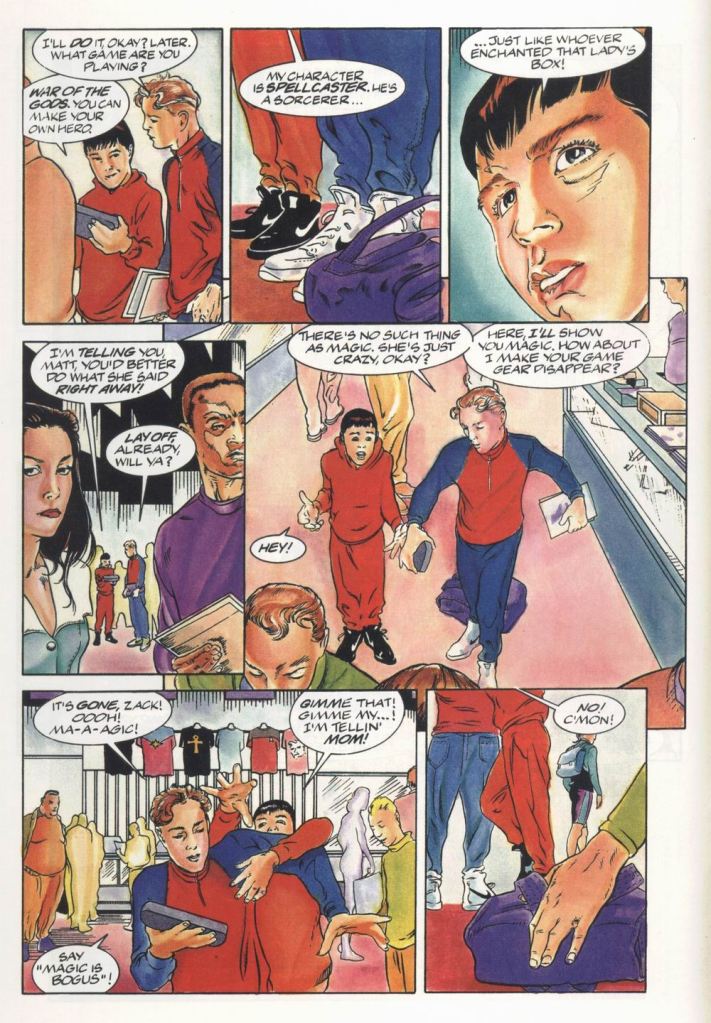

First off, there’s no getting around the fact that the talent producing this first issue are at best amateurs with a bit of promise showing through. The main writer was Jan Childress, who had come to Shooter’s notice when he complained publicly about the dearth of worthwhile characters of color in the field. Shooter invited him to come on board and work to change that–but THE GOOD GUYS doesn’t really tackle that question very much. There are a few black characters in the book, but more often than not, they talk in stereotypical dialogue. They certainly don’t register as well-rounded characters.

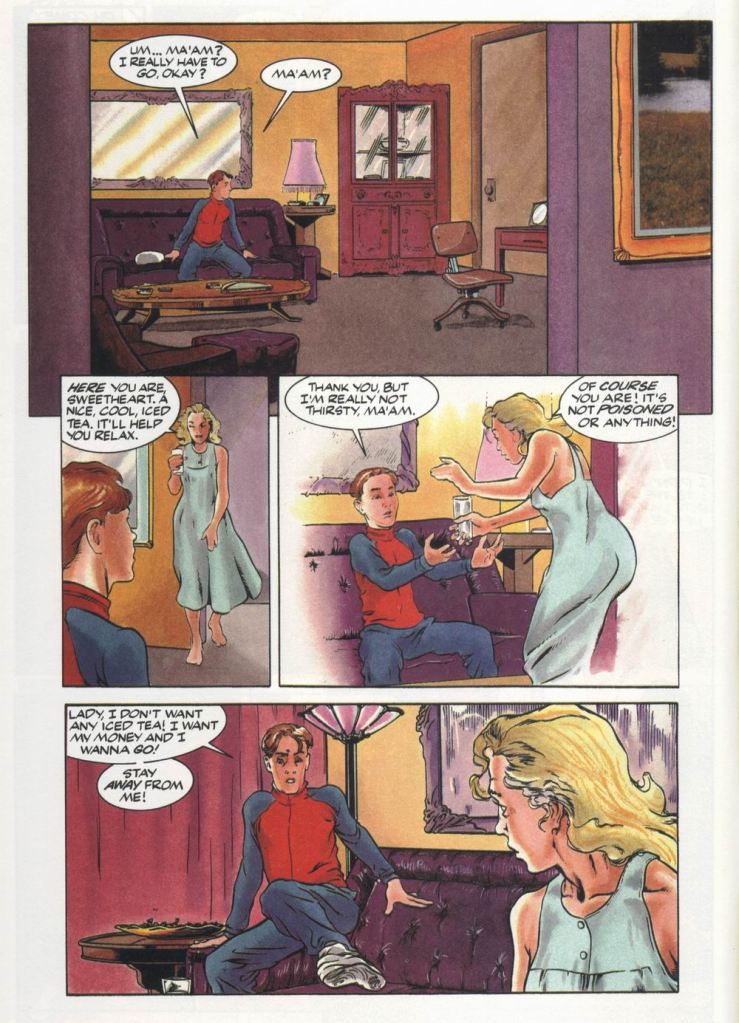

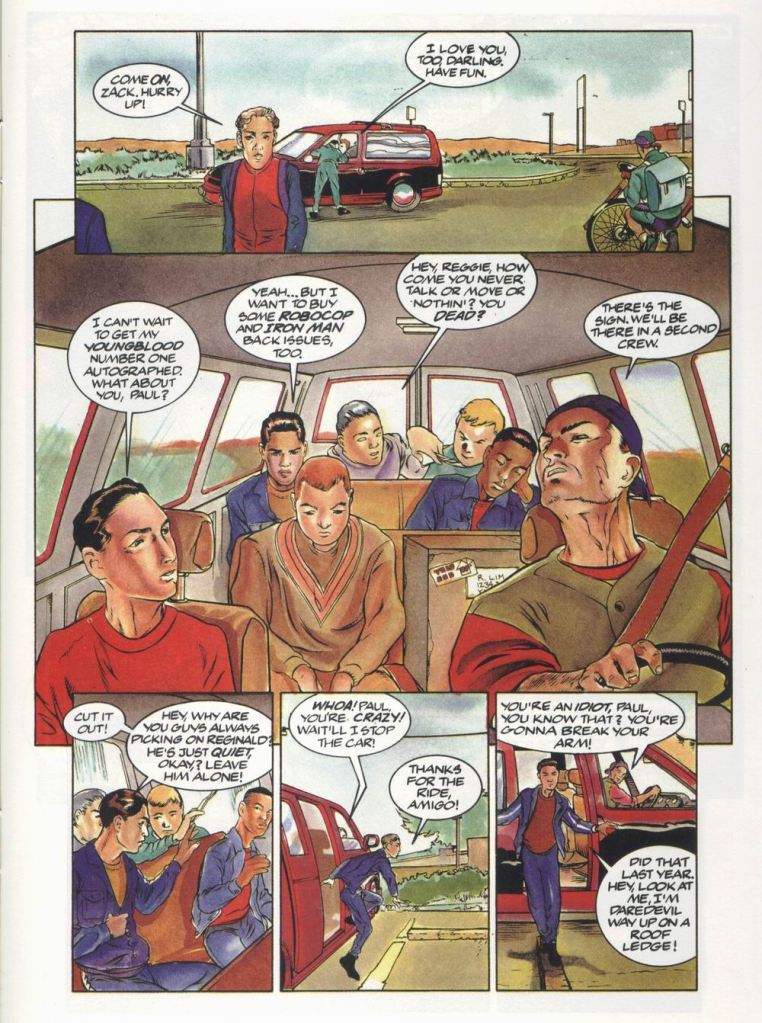

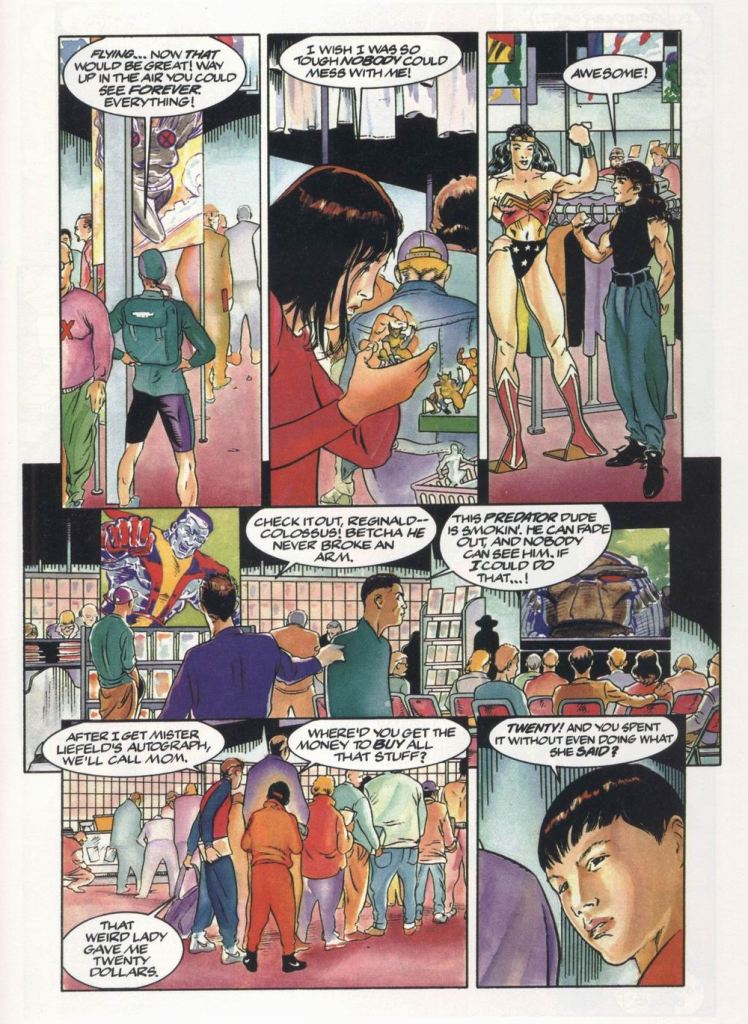

And that’s a problem with the cast of the Good Guys as a whole. Nobody really stands out from the bunch. For one thing, a lot of the character designs look generic–it can be tough to even keep track of who all the characters are as they look so similar. On top of that, the series make a key and central mistake: it attempts to introduce too many characters at once. There are seven new lead characters in this book, to say nothing of supporting players, villains and incidental characters. It’s a lot of get one’s arms around. Throughout the course of the series’ nine released issues, this situation doesn’t really get any better. The main seven never break out from being broad types, blossoming into three-dimensional characters. Most of their dialogue feels generic and interchangeable throughout the run. On top of which, nobody really has a sensible motivation for half of what they do in the series. The Good Guys become a team of super heroes because, well, that’s what you’re supposed to do when you find yourself with super-powers and surrounded by others in the same boat.

Some of this comes down to the way this series was managed moving forward. Childress only stays with the book for four issues, and with increasing portions of it being credited to Shooter and his close friend Jay Jackson. Thereafter, the remaining issues are all scripted by a different person every month. While Shooter and Jackson are credited as doing the overall plotting, this makes the book feel utterly generic. Some of the creators working on this series were well-established professionals, but there just isn’t enough to the characters for them to do anything noteworthy with, and so they churn out generic dialogue to fit the generic situations the stories present. In other words, nobody sees to have agency in charting the direction of the series. My guess is that Childress and Shooter hit some divisive point between their two perspectives, and Jim, as the head of the company, won out. If it had only been a change of creative team, the book might have righted itself, but it became a rolling problem all the way through the final issue.

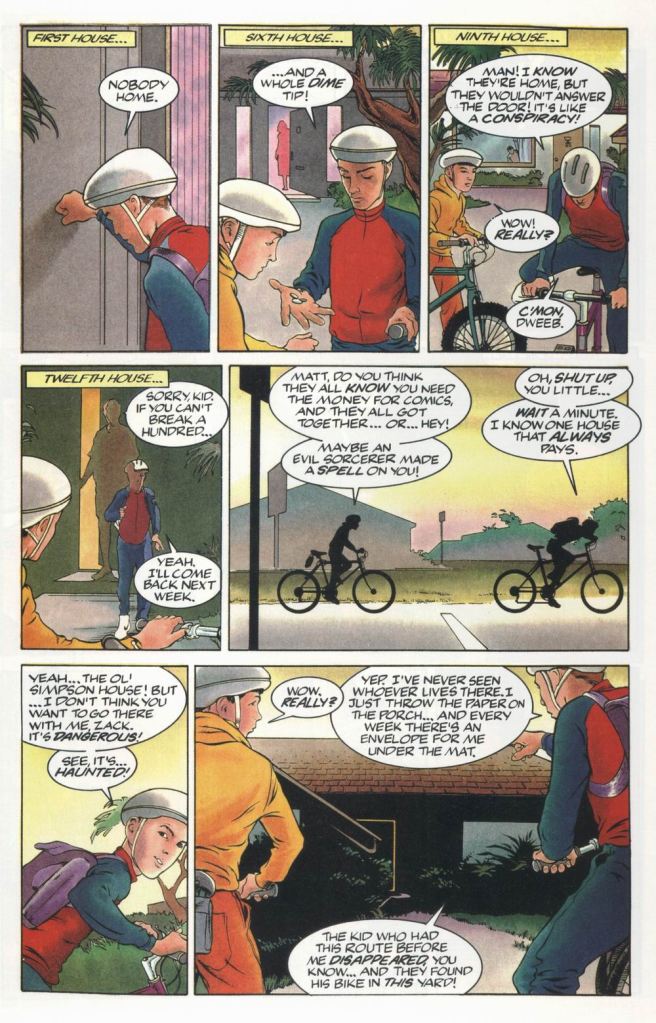

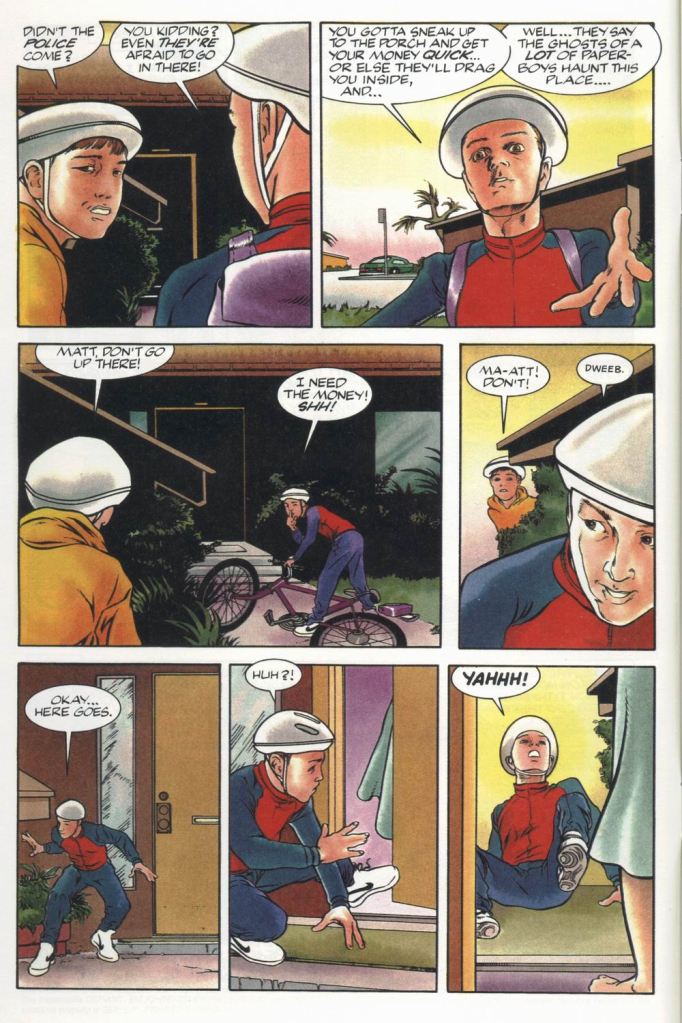

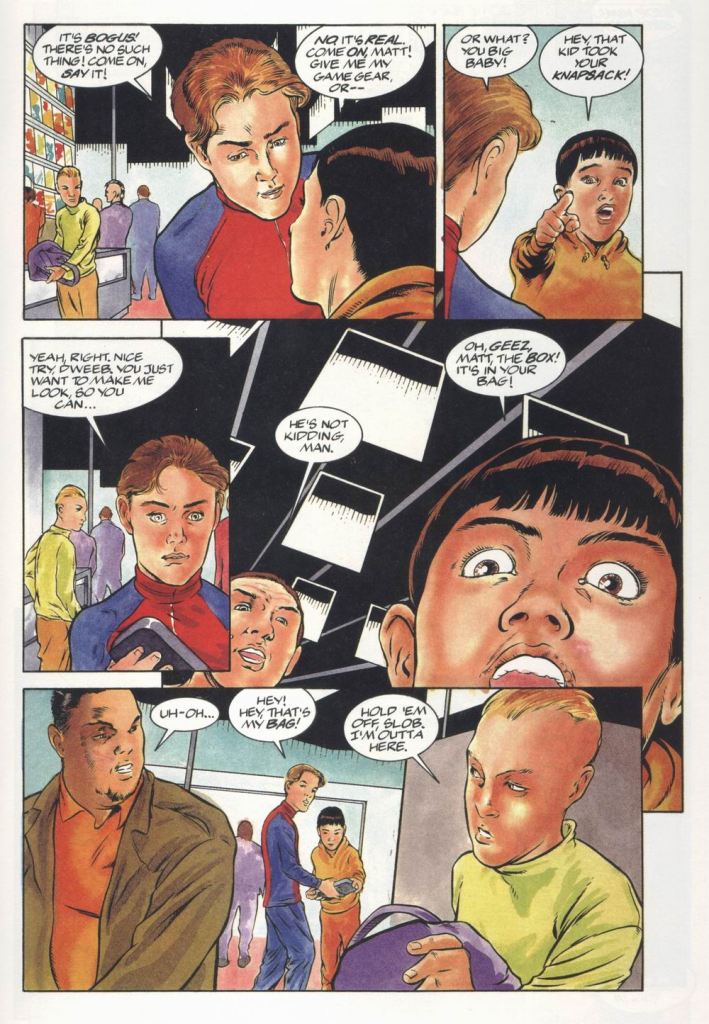

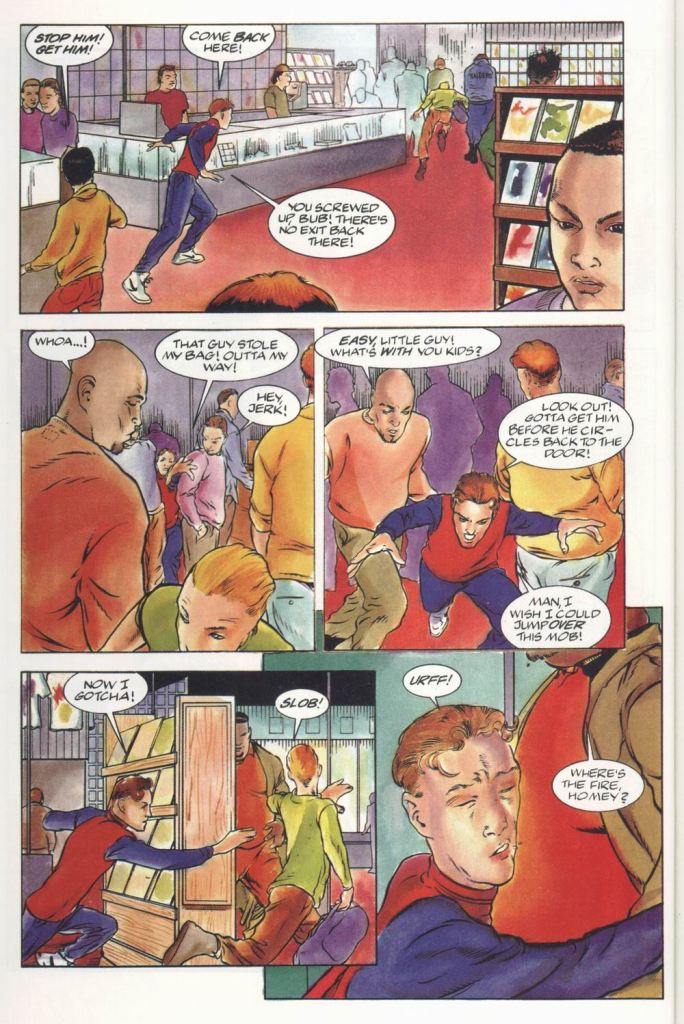

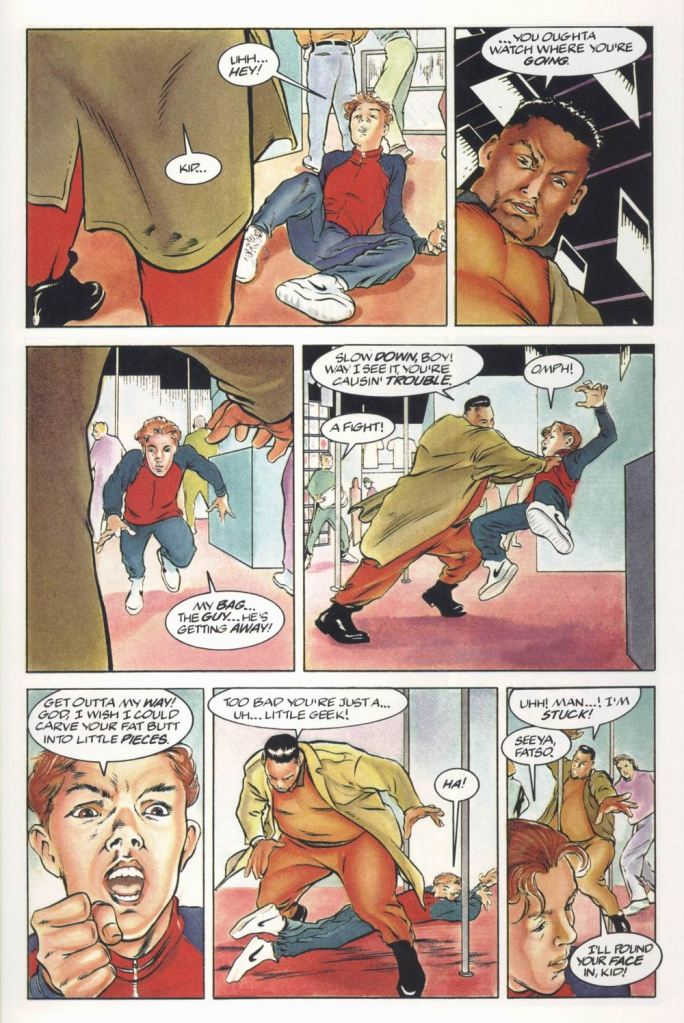

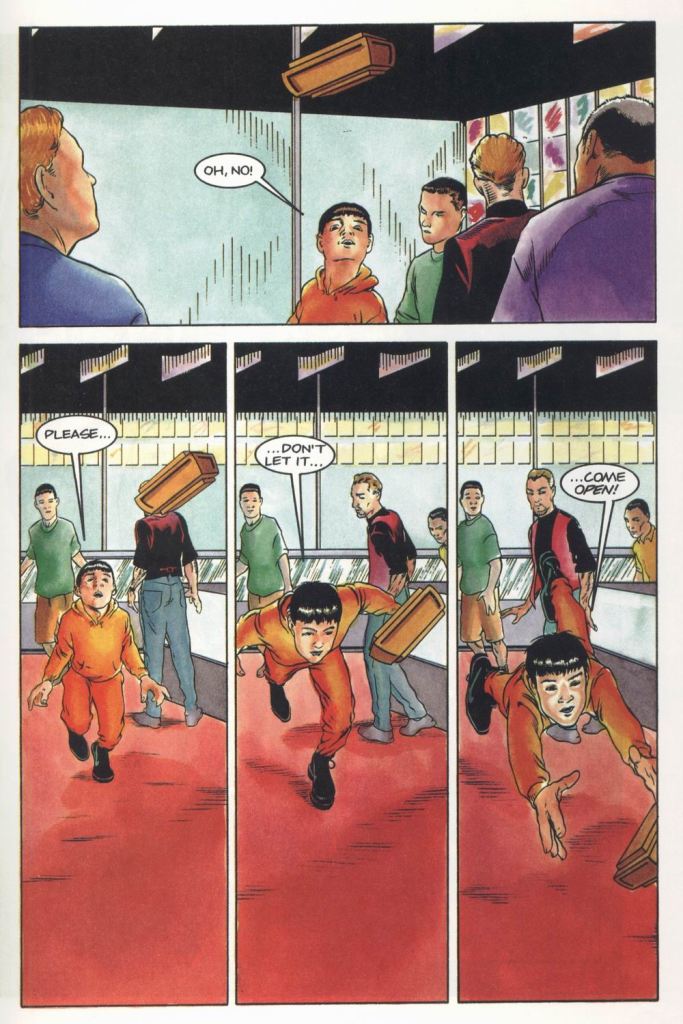

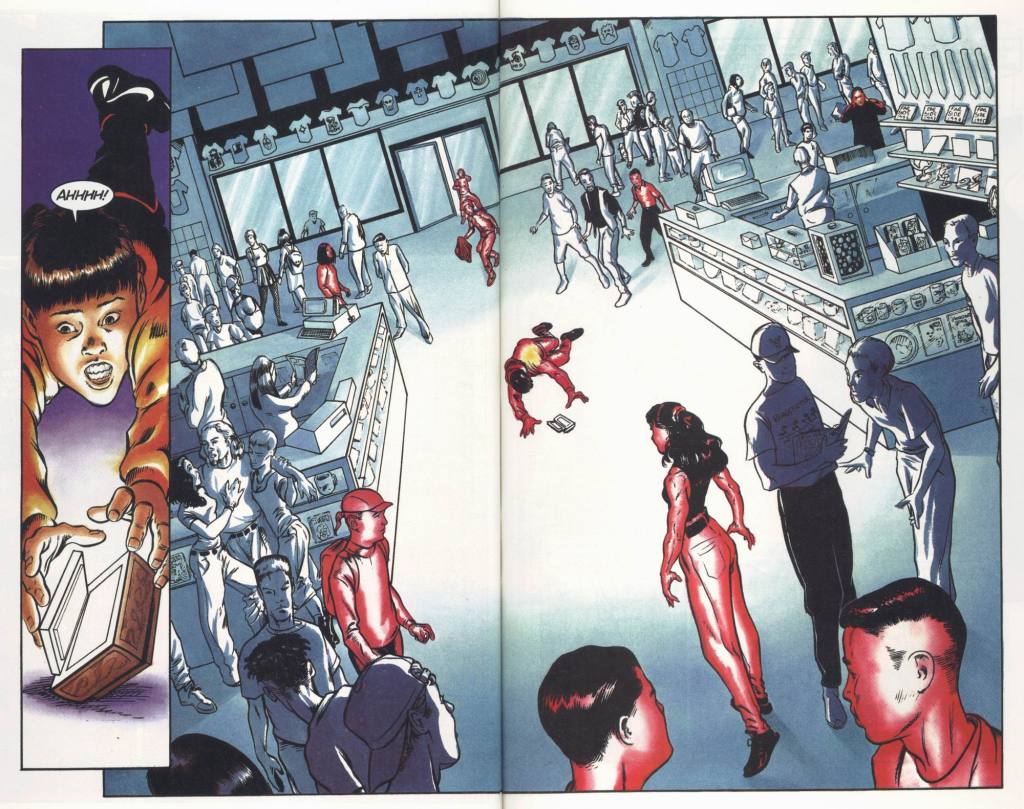

Let’s talk about the artwork a little bit. This first issue is credited to an artist called Grey, with some assistance from Alan Weiss and a young Adam Pollina. Grey has certainly got talent, but the speed at which he’s having to work coupled with the schedule (and this first issue is 45 pages long to boot) means that he’s unable to put his best foot forward here. You can see the art get looser and looser as the issue goes on and the deadline looms. In many panels, the figures seem unfinished and open, as though hoping that the coloring will make up for the lack of detail and specifics. On top of that, there are places where he’s clearly going for a likeness and he simply can’t pull it off, thus making one of the selling points of the project into a negative. What’s the point in these characters looking like a bunch of specific fans if they simultaneously look poorly drawn? It’s also not hard to spot the places where Weiss and/or Pollina have been called in to do some redraws.

Everybody was trying to do more in color at this point in the 1990s, following the example set by Todd McFarlane and Steve Oliff on SPAWN. Here, though, this issue sports five colorists, a couple of whom have a ton of published credits to their name. But the painted blueline coloring here doesn’t work at all. Rather than focusing the eye on the most important subjects in every panel, every page is instead awash in a sea of watercolors without a whole lot of contrast to them. If the linework is sparse and underaccomplished, the coloring does nothing to offset those deficits. It’s akin to looking at these pages through a haze.

I should probably also mention that Shooter’s love of medium shots is apparent all throughout this comic and the subsequent issues. Every opportunity for dramatics and dynamics is squandered in favor of long images that attempt to show the situation in toto, but which get let down by the haphazard nature of the artwork. There’s no rhythm to the artwork, no tempo. Consequently, every moment takes on the same degree of importance as every other moment–nothing stands out.

The lettering and balloon placement is also a bit haphazard. It’s not so bad in this first issue, but as the run goes on, it becomes steadily more and more amateurish. I’d imagine that this was all down to Shooter having to make do with what he could afford, which pretty well boiled down to newcomers and old friends who would do him and his new venture a solid. But the choppy lettering often makes pages a chore to read, even though they’re laid out in an almost diagrammatical fashion.

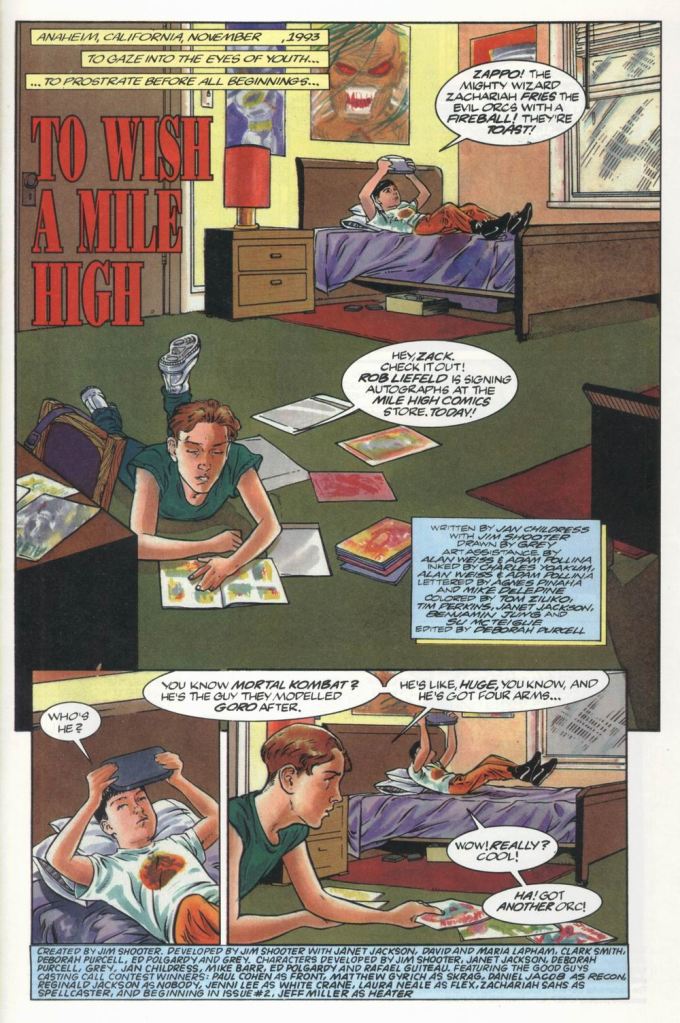

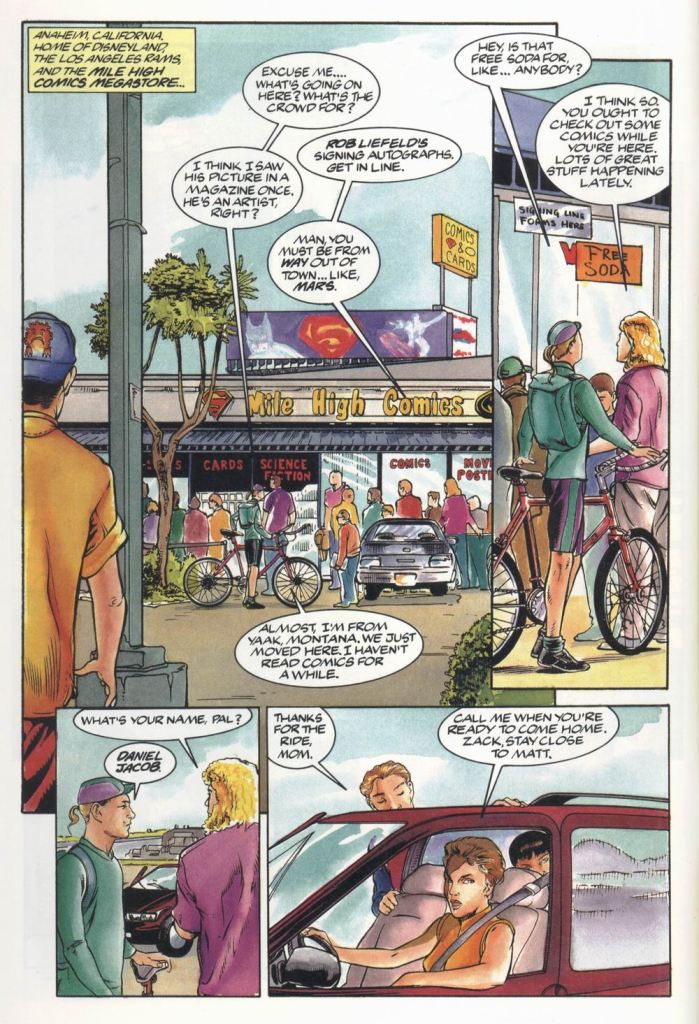

There’s also a ton of comic book in-joking in this series, perhaps more than is advisable. It’s kind of fun that the event that brings the soon-to-be-Good Guys together is a store signing at the real world Golden Apple Comics by Image creator Rob Liefeld. (Hey, did he get a magic wish granted when the box was opened? That might explain a bit about his overall career trajectory.) But issue after issue, there are asides and comments concerning stuff that’s going on in other companies’ titles. Some of this is an outgrowth of part of he set-up: one of the kids’ Dad owns his own comic book shop, so it becomes a bit of a loci for the group’s subsequent adventures. But it doesn’t feel fun so much as attempting to draft off of the appeal of more popular properties.

There were editorials during the run of the series about a proposed collaboration between Shooter and Liefeld. I would have loved to have seen what that looked like, as I can’t think of two creators whose approaches to the material are more diametrically opposed, and who are neither terribly comfortable with compromise. That right there may be exactly why we never got to see it, ultimately.

This page is in no way up to professional standards. Look at all of the wonky anatomy, the barely-finished faces, the stiff and unconvincing storytelling. And look at how the coloring almost aggressively focuses on everything apart from what the point of the specific panel is. In that first panel, for example, why is it that the fleeing shoplifter gets lost among the background? He’s one of the two key elements that you want to be focused on in this minute, him and his pursuer. Same thing in the second panel, which reads as though that one bald bystander is the star of the show.

I think I read the first three issues of THE GOOD GUYS at the time of its release, wanting to like it, wanting it to be better, before simply giving up on it. Having now, years later, sought out and read the remainder of the run, that was the right choice. In subsequent issues, elements from other titles in the Defiant line begin showing up. But universally, when they do they are treated as though the reader already knows chapter-and-verse about who they are and what they’re about. It’s maddening, particularly from Shooter who is vocally such an absolute fiend about storytelling clarity.

THE GOOD GUYS isn’t by far the worst comic book series ever done, and it does still evidence a bit of charm and potential. But it’s a serious misfire nonetheless.

Shooter and Defiant eventually ran out of funds and had to shut down production. Subsequent to that, Shooter once again dusted himself off and found a new backer for a new venture. This time it was Lorne Michaels, who underwrote Broadway Comics with Shooter at the helm. And like Valiant and Defiant before it, Broadway’s output it really interesting to study. I’m sure I’ll cover at least one of their titles at some point.

So the premise of THE GOOD GUYS is that somehow there was something contained inside this box that granted the wishes of the assorted people who were exposed to it when the box came open in the middle of the comic shop. This included granting super-powers to seven of the customers, who would become the titular Good Guys.

Now, none of these individuals know one another before this accident, apart from the brothers Spellcaster and Skrag. But they wind up immediately grouping up for pretty much no reason at all and getting involved in a series of skirmishes as they work out their powers and how they came by them.

And of course, they all get costumes and code-names as well. This helps to be able to keep them all straight, but not enough–especially since their costumes all carry similar elements and color schemes to one another. And really, this whole series would have been better with a more focused cast of, say, five main characters rather than seven–even if it wound up bringing in the other two characters later on.

The big kicker to this first issue is the fact that the woman who gave Matt the box in the first place has a history of mental illness, and the box itself was just an ordinary thing. So was there anything inside it, or did everybody coincidentally get powers when it was opened/ The series never gets around to answering this, but given the Defiant line’s heavy use of quantum theory in the creation of its characters, I’d hazard a guess and say that the event was somehow tied to that in some way.

i thought Broadway was Shooter’s most interesting venture by far, but by that point the industry had contracted to the point that I doubt any of the titles were widely read. I really dug some of those series, though.

LikeLike

I think the only Defiant comics I got were the first issue of WARRIORS OF PLASM (not the card set) and the two issues of PRUDENCE & CAUTION.

LikeLike

Here is my thoughts as I was reading what Tom wrote: I thought Tom said there were superheroes in this and why not do the origin in flash back over a number of issues since the first issue is 45 pages long. Imagine if Stan Lee & Jack Kirby waiting that long to introduce the Fantastic Four or Thor. If they didn’t know each other ( except for the brothers ) did their powers visibly manifest for them to know to come together if for no other reason than you got powers too? Maybe like the Marvel mutant Caliban who has the ability to sense other mutants, they have the power to sense other powered beings?

LikeLike

Besides the Fantastic Four the only other teams that got their powers at the same time are the Power Pack kids [ Power Pack#1 ( August 1984 ) Marvel’s second family and like its first the FF they too went into action in their first issue ] and the second is Malibu Comics ( Ultraverse ) team the Strangers [ The Strangers#1 ( June 1993 ) ] who I know of from Break-Thru#1-2 ( December-January 1993-1994 ) ] and Wikipedia says they went into action against their future teammate the sorceress Yrial. So 3 examples of introducing characters correctly.

LikeLike

“Unfortunately, he was often a mercurial boss who created a lot of friction among Marvel’s freelance and editorial staff as time went on. Some of that was unavoidable; as the EIC, Jim was ultimately the guy who often had to say no. But it wasn’t all unavoidable. Eventually, matters reached a head and Shooter was ousted by Marvel.”

My understanding is that Shooter’s termination had nothing to do with conflicts with subordinates. The core problem was a series of increasingly bitter disagreements with Marvel president James Galton while Marvel was for sale in the mid-1980s. When New World bought Marvel in late 1986, Shooter got on their bad side by advocating for a smaller publishing line. In early ’87, Shooter sent the New World executives a letter denouncing Galton’s ethics. Being less than happy with Shooter themselves, they forwarded it to Galton, and told him to do with Shooter what he wanted. He fired Shooter.

I’m not saying Shooter wasn’t a bear to deal with for staffers and freelancers during the last year or so he was at Marvel. By almost all accounts he was. But it wasn’t the reason Marvel let him go. I know there are a number of butthurt people in the comics community who want to believe otherwise, and the dreaded Comics Lore now reflects that. But that doesn’t make it so.

LikeLike

I read some of Jim Shooter’s statements about his opposition to Jim Galton, but what did Shooter do that prejudiced New World against him, so that they simply turned him over to Galton’s tender mercies?

LikeLike

Shooter believed Marvel was publishing too many titles. It was beyond the production staff’s ability to comfortably handle, and forced the usage of what he thought was substandard talent. He also thought Marvel was setting itself up for a business fail along the lines of the DC Implosion.

John Romita Sr. has gone back and forth over whether he backed up Shooter in discussions with the New World people. But when I asked him about it, he said Shooter had his support. According to Romita, the New World people wouldn’t hear of it. They wanted Marvel publishing more than it already was. Romita also said he thought that was the beginning of the end for Shooter there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There is probably a great business book to be written in Shooter’s career. Sean Howe handled the Marvel part of it brilliantly in Marvel Comics: the Untold Story .

The legal machinations of how he was forced out of his Marvel contract and forced out of what was probably an equity stake in Valiant would probably be a fascinating law review article.

LikeLike

The whole look of this books turns me off.

This has the same premise as The Strangers, which Malibu launched a few months earlier (not that the idea is so unique it had to be a knockoff). I thought that book handled the whole concept of six strangers becoming empowered and joining forces better. As the other people on the Strangers’ cable car also got powers, I wonder if the rest of the comic-book store did.

The ending twist makes no sense and would have annoyed me rather than intrigued me.

Stryker Z in Kurt Busiek’s Power Company was a good look at the “I got powers, guess I’ll fight crime” type of character, or so I always interpreted him.

LikeLike

The New Universe title D.P.7 (1986-89) could be another possible influence on GG, given that Shooter himself was involved to some extent in that title’s launch. That might also apply to other NU titles but I can’t speak to them because I blocked them all out of my memory.

LikeLike

So without intending to do so, New World duplicated the approach of Martin Goodman: more market share is always good, and there’s no way you can ever hurt your brand with too much crap.

LikeLike

I assume anyone reading this post following June 30 knows of Shooter’s passing on that date, I’m glad we got some further info here on his significance to the medium.

LikeLike