Well, it had happened again: I had missed an issue of a beloved comic book series, this time THE FLASH. While my ardor for it had cooled somewhat as my attention was taken up with my exploration of the Marvel Universe, the character and the book remained a sentimental favorite. But in recent months, my local 7-11 had seemingly stopped carrying the title, and I’d only been able to keep up with current issues by coming across them haphazardly in other outlets. And this was the time where my luck in that regard ran out. What’s more, it was an issue of some significance that I had missed: the final one edited by Julie Schwartz, who had been my unknown guide into the world of comics, and whose books I had liked best as a kid. He’d been editing the series since 1959, so almost twenty years, and before that the four SHOWCASE appearances that extended back to 1956, so you can’t say that he hadn’t put in his time. But even without realizing the editorial switch, I could feel that something was a little bit different going into this issue.

The issue was still drawn by Irv Novick, so on the surface it resembled every issue of THE FLASH that I had ever bought new. Unbeknownst to me, this would be his final moment on the series, as new editor Ross Andru decided that the book needed a visual refresh as well as a story one. He’d been drawing the series since #200 many years earlier, without missing a beat. Irv’s work on the character had defined the Scarlet Speedster and his world for me, and while some very good people worked on the title after this (including a returning Carmine Infantino in a couple of years), it was never quite the same for me hereafter. Novick’s work wasn’t splashy, but he told a story dramatically and well, and he was able to capture something of the flavor of Infantino’s approach while updating it for the 1970s and mixing in just a little bit of the Neal Adams approach to make it more contemporary. I’d miss him here.

At the outset of the issue, it seems like business as usual. But Andru had a desire to update and modernize the character, which began to be felt in a couple of pages. This included starting an array of subplots: a mysterious girl who is obsessed with the Flash, experiments being conducted at a local penitentiary to alter criminal behavior through shocks delivered to the brain, friction between Barry Allen and his wife Iris about the twin responsibilities of his job and his career as a super hero keeping him away from home and her, and a new partner for Barry, one that would involve him in the disappearance of a large quantity of confiscated heroin from the police lock-up. There was a lot going on here, and some of it was designed to head towards one of Ross’s major goals: the death of Iris Allen. But we’ll get to that in due time.

The new editorial direction of the series was deemed important enough that the attached house ad, which ran in this issue, was commissioned, previewing both this issue’s cover and the next. Should I spoil things now by telling you that, like #269, #271 was another issue that slipped frustratingly through my grasp? I wouldn’t read either of these issues for years to come yet.

There were a lot of house ads scattered throughout this issue, all of which were new to me. This one focuses on DETECTIVE COMICS, which had been merged with BATMAN FAMILY in order to prevent its cancellation during the DC Implosion. The title had been doing poorly enough that it was on the chopping block, but Paul Levitz had the brainstorm of just putting the DETECTIVE COMICS banner onto BATMAN FAMILY, which was still selling well, and thus preventing the series the company was ostensibly named for (though that DC more conversationally stood for Donenfeld Comics rather than Detective Comics. But the latter was the official story.)

Anyway, this issue opened with the Flash getting his head handed to him by the Clown, a silent new villain who was committing a crime spree that befuddled the authorities. Picking himself up, the Flash races over to his day job as police scientist Barry Allen–getting there late, of course. His aggravated boss, Captain Paulson, tells Barry that Allen’s old college thesis about the reformation of the criminal mind is the basis of the Nephron Process and has Barry report to Professor Nephron at State Penitentiary to get a look at it. Barry phones Iris at home, apologizing about both missing breakfast due to his conflict with the Clown and now having to miss dinner in order to make his appointment at the prison. The usually-understanding Iris hangs up on him, a sign of trouble in paradise.

Another house ad, a centerspread this time! With the Superman movie on the horizon, DC was puling out all of the stops to promote their lead character and the many titles he was appearing in.

And even more upcoming covers were featured in this subscription push for Dollar Comics, publisher Jenette Kahn’s passion project.

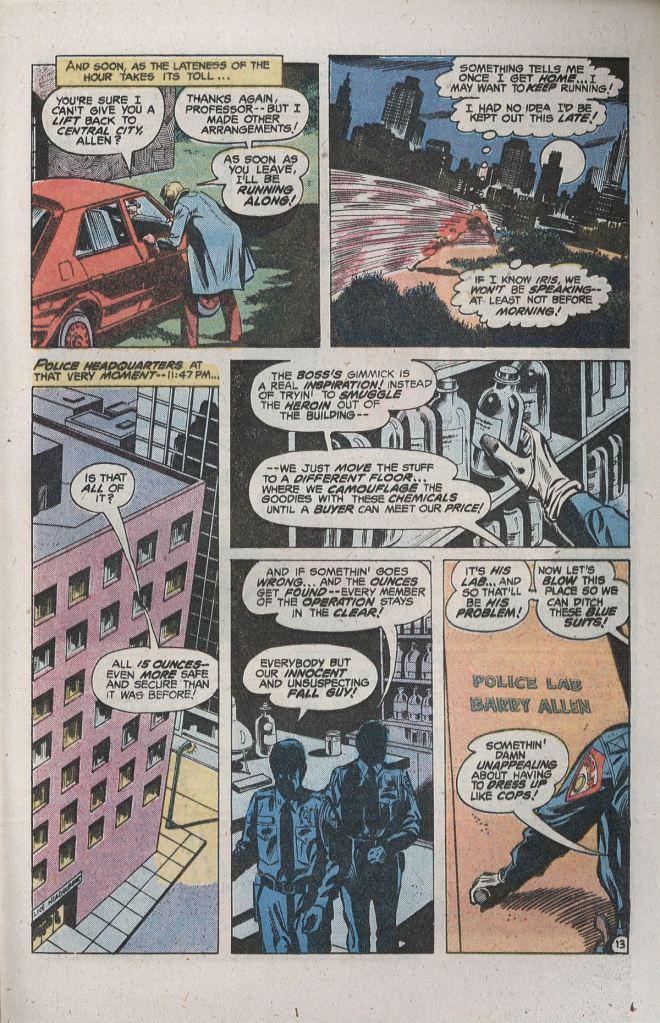

After showing his process to the visiting Barry, Professor Nephron asks for a volunteer among the prisoners, and Clive Yorkin, a young man incarcerated for life for a variety of crimes, offers himself up to the program. This will come back to roost in the issues to come. Meanwhile, two men dressed as cops in the Central City Police Department (they can’t actually be cops, as the Comics Code then still mandated that authority figures had to be depicted as honest and trustworthy) have smuggled the heroin out of the lock-up, and they stash it in Barry Allen’s lab until they can find a buyer for the goods. They figure that, even if it’s discovered, Allen will be on the hook for the crime.

The next morning, Iris is giving Barry the silent treatment, which seems a bit juvenile for a married couple, but it certainly gets the point across that there’s trouble here. Barry heads out in costume for his “morning jog”, and his attention is attracted by skywriting high in the air spelling out HA-HA. Correctly figuring that this is a challenge from the Clown, the Flash races to the whereabouts of his foe, who is riding a gimmicked-up calliope and proceeds to attack the red-garbed speedster. The Clown winds up tricking the Flash into the vicinity of an explosive, which he promptly sets off. The hero is able to contain much of the blast, thus preventing any loss of life or property damage. But as he’s doing so, he makes a misstep, and is propelled into a nearby wall–literally. Having been vibrating intangibly, the Flash passes into the brickwork halfway and is stuck there.

Presumably, the Flash’s legs didn’t actually merge into the structure of the bricks, as that would have caused a massive explosion and fatal damage to him. But he still needs a minute to collect himself and vibrate free. And that’s a moment that the Clown isn’t about to give him. The silent killer fires a barrage of rockets at the stuck speedster–and that’s where this issue is To Be Continued. With its emphasis on soap opera, running subplots, some more real-world situations (heroin!) and a cliffhanger ending, one has to assume that editor Ross and writer Cary Bates were taking some cues from the sort of pacing that Marvel was then putting out. It was a bit of a different flavor for the Flash, and it would only become moreso as subsequent issues came out. But we’ll get to those as we go.

The Flash-Grams letters page runs for two pages this issue, and includes a final letter paying tribute to Julie Schwartz’s tenure as editor. Without this letter, I wouldn’t even have been aware of the change to be honest, even though I could feel that the book was somehow different. And it includes yet another pair of upcoming covers–in the wake of the DC Implosion, the editorial staff was doing everything possible to improve their sales, and nothing was quite as impactful as reproductions of upcoming issues.

God, I hated this era. So heavy-handed at trying to turn Barry into a Peter Parker type whose life never works out.

LikeLiked by 1 person

no one hates this era – that thematically lasted until the title was cancelled with #350 – more than I do. I stopped reading after Iris’ ridiculously dumb death but would pop in every few issues to see if it course corrected, nope, it just got worse. Barry stalking Fiona? Sure, why not? Flash on trial for what seemed to be years? yeah, go for it. Blech. And the art went downhill fast fast fast and stayed there. For me, this is the quintessential example of someone not really understanding the character they were writing, nor what the fans were interested in seeing. Blech.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Killing Iris was a huge mistake. Making her antagonistic was too. unlike Jean Loring, Iris had been rehabbed out of the harridan girlfriend trop she’d been at first. No love interest ( and they only tried two, right?) filled the void successfully. If Andru had truly wanted something great to pull in eyes and readers, maybe Cary Bates should have been given more creative freedom. His Superman Elseworlds years later along with the wonderful True Believers mini for Marvel showed that as awesome as his output was back then, he had greater things inside him.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Agree to all of it. One of the best things about The Flash in the 70s was that he was a suburban husband and a super hero who wasn’t stuck in the endless loop of his girlfriend trying to suss out his identity. re: Iris dying, this was a period at DC where the extent of the editor/writer imagination of how to revitalize a character was to kill off a major character. So glad when someone reversed that – it didn’t really make a lot of sense but I hand waved it away and was happy that she was back. Her return was such a great part of the 90s Wally stories.

LikeLiked by 3 people

“…Where the extent of the editor/writer imagination of how to revitalize a character was to kill off a major character…” Not just at DC. And hasn’t stopped with the 70’s. Still happening, with just as adverse effects. It’s a huge loss to the Batman books for Alfred to die. After being integral for ~8 decades. Anything for a sales bump. Including changing who wears the hero’s costume & uses the identity. But they almost all seem to revert back to the original, whether it’s after several months, or a couple of decades. Now they have multiple characters side by side using the same name.

LikeLiked by 1 person

While I can’t disagree that Flash was probably due for some kind of shake-up, I was not a fan of the direction they chose. The general dark and depressing tone, unappealing artwork, and mediocre new villains like “The Clown” and that Yorkin character (who’s storyline just dragged on and on and on…) finally made me drop what was once one of my favorite series. When they finally bumped Barry off in Crisis years later, I was more relieved than saddened…better to go out in a blaze of glory than to live like this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sadly, that also was my response to Barry’s death. Bates also had so much more talent than showed here. He concurrent work proved that – would have loved 30 more years of – I think it was called Silverman?

LikeLiked by 1 person

The end of the days when half the JLA were happily married – what was so wrong with that idea that they had to tear it all down and make everyone miserable?

LikeLiked by 2 people

Superheroes being married, especially to spouses who aren’t superheroes, has been a major debate for decades for both DC & Marvel editorial. Superman & Lois chased each other around for 50 years before getting married. Including, a stretch of however many years, around the time of this issue of Flash, where an adult Lana Lang kept getting in the way. Now Superman’s marriage to Lois, ~35 years later, seems to many to be too essential to lose. And the lack of their marriage (or maybe really the way they interacted w/ each other during the absence of their marriage) was one of the downsides cited of the “New 52”. Superman is said to be one of those characters better suited for marriage. Why? Because marriage is seen as more “traditional”, or “old school”, and for decades he’s been THE “old school” superhero?

But you’re right, in the 70’s, several of DC’s heroes were married. Flash, Atom, Hawkman & Hawkgirl, Aquaman (though it got rough in the 70s), Elongated Man, Adam Strange. Not so with Marvel heroes. I can only think the Pyms & the Richards in the 70’s. (When did Wanda & Vision marry?) Was DC changing to reflect Marvel, in hopes of appealing more to an audience that was growing older? That “stable marriages” were based on the societal norms of the previous decades? Those other married DC heroes couldn’t sustain a solo book for long. But were their marriages the biggest reason for that? Was being single better for sales for Hal, Diana (who was often shown as practically married to Steve Trevor), Bruce, etc., etc.? Green Arrow & Black Canary were a couple, not really “single”, and both were back up features in other books. Was Flash selling worse than Green Lantern or Wonder Woman?

LikeLike

Hard to imagine any series back then selling worse than Wonder Woman. Vision and Wanda married in Giant-Size Avengers #4 (the internet says 1975) in a double wedding with Mantis and Plant Zombie Swordsman in the very anticlimactic ending to the Celestial Madonna Saga.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hated to see Irv Novick leave this title. His art was perfectly suited to the Flash. I agree with many of the comments above – the darker issues from 271-350 held little interest for me. I would check in periodically but be continually disappointed. The changes did a lot to ruin what had been one of my favorite characters.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think the Andru-edited era of FLASH was very uneven , but I loved the Wein-edited Bates-Heck run that followed it up, and thought there was a lot of engaging material between there and the sadly-interminable “Trial of the Flash” storyline.

I think killing Iris brought a lot of attention to the book, which is the name of the game. If it could have been done another way, that’d be fine too, but shaking up Barry’s life and giving him a fresh start somehow was worth doing.

LikeLiked by 2 people